-

- Dems take on HIV/AIDS, Supreme Court

- Survey: Fewer Americans see children as key to a good marriage, say sharing chores more important

- Former leaders of ex-gay ministry apologize

- Bush administration emphasizes faith groups for AIDS prevention

- Massachusetts inmate’s bid for sex-change surgery draws big costs

- Fired CBS News producer sues, alleging gay bias

- National News Briefs

- World News Briefs

Arts & Entertainment

Out at the Movies

An interview with the duo behind ‘Eagle vs. Shark’

Published Thursday, 05-Jul-2007 in issue 1019

Nerds of a feather

The first thing that needed to be investigated was Loren Horsley’s mouth. Her birth mark was real.

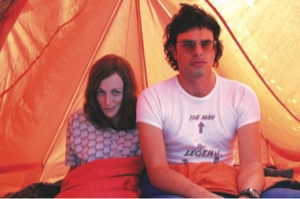

The actress/co-author was in town with her director/boyfriend Taika Cohen, sitting on the floor of their hotel suite and talking up the release of their quirky romance Eagle vs. Shark.

One of the few qualities Horsley’s character “Lily” shares with “Jarrod” (Jermaine Clement), her on-screen object of affection, is the sizeable specks on their upper lips.

Instinctively bringing finger to lip, Horsley admits, “It’s real, but they colored it in a bit.”

Jarrod’s was bogus. “It was a prosthetic thing,” she says, lowering her voice. “It kept sliding around all over the show; hell for the continuity department.”

Eagle vs. Shark is a New Zealand indie about two painfully awkward social misfits who find love the hard way.

After seeing the trailer, the initial impression was that of a Napoleon Dynamite with regional accents, but the director is quick to refute all but the most superficial of parallels: “I’d say Napoleon Dynamite is nerd comedy. I’d say this is an outsider film.

“Even so,” he continues, “this is not a straight-out comedy. At heart, it’s a dysfunctional family tragedy under the guise of a comedy. In Napoleon Dynamite you laugh at the ridiculousness of the characters.”

“We saw Napoleon Dynamite,” Horsley jumps in, “and everybody in it played for laughs. We had already written the story and Taika said, ‘Shit, he’s like Lily and Jarrod combined.’ That was really as far as the thought went. We were playing more for the heart.”

Jarrod is counter girl Lily’s customer of choice at Meaty Boy Burgers. When lunchtime comes around, Lily watches the clock for the precise moment when she’ll have her chance to serve him. While there is a sweet sincerity behind Lily’s longings, Jarrod is a poster boy for Assholes Anonymous.

In order to level the playing field, I decided to join them on the floor before breaching this potential sore point.

“How could Lily fall for such a charmless load like Jarrod?” I ask.

Both were quick to jump to their character’s defense. Horsley was the first to stir. “Who you fall in love with is totally inexplicable,” she says, her voice accelerating. “To her, he’s handsome and he’s got a great walk, a great jaw and he’s got big lips.”

Cohen adds, “He’s the danger, excitement and adventure that she doesn’t have in her life.”

“And he’s charming to her. Subconsciously, she recognizes that they’re similar animals in a way,” Horsley concludes.

The thought of lost Lily and arrogant Jarrod being emotionally analogous doesn’t compute, and if it did, it would probably make me dislike her all the more.

Hosley is flabbergasted. “Really?” she moans.

He’s quick in bed, lies to her at every chance he gets, smashes her birthday cake and sports a hideous Moe Howard mullet. I stood behind my original charge of extreme assholism.

“It has to do with the transformative power of kindness,” Horsley begins in her best “Oprahese,” trying to explain the effect she feels Lily has on Jarrod. “If she could reflect that to him, he might start reflecting it back. He had a shit life and I think the transformation in him was enough. The guy is a mess. He’s a true character. I know people who stick with people who treat them really badly. That’s a truthful dynamic in the world.”

Cohen argues, “It’s a truthful depiction of how humans interact with each other emotionally set in a romantic comedy background. In a normal mainstream romantic comedy, Jarrod’s the guy who gets left by the girl who goes off with a good-looking glass blower who’s a true artist. Those characters that get left behind never get a chance to take any steps forward or to change.”

The room heats up and a change toward the positive is in order.

“Do you have to put up with unions and Teamsters when filming in New Zealand?” I ask.

“I don’t even know what the hell a Teamster does,” Cohen jokes. “We don’t have Teamsters. Anyone can bring an actor to work. We’ve only got camera departments and they’ve got their representatives.”

“At the end of the day,” Horsley says, cutting him off, “everybody picks up gear and brings it back to the truck.”

Before turning the conversation over to another potentially unpleasant subject, the talk shifts to bashing Forrest Gump and a brief lament over the fact that they won’t have enough time in town to visit Balboa Park.

Feeling confident, I observe that while the film’s exteriors display a keen awareness of space, the majority of the indoor scenes are shot in suffocating close-up.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” the director says in defense of his frames. “I think there’s a good mix in this film.”

A nerve was touched.

“I hear a lot of people say you’ve got to earn the close-up,” Horsley confesses before asking whether I felt the film was rhythmically disjointed.

“Frankly, yes,” I reply, “which brings to mind the Buster Keaton quote: ‘Drama is close-up; comedy is long shot.’”

“This is a film,” Cohen says while gathering his thoughts, “where it was very important not to say [to the actors], ‘We’re making a comedy, come here with your comic performances.’ This is more like a Mike Leigh film,” another director who uses an overabundance of close-ups, but I held the thought.

“If you keep all the performances truthful,” Cohen continues, “the comedy in the script and the situations comes through.

Not wanting to end on a sour note, it was time to, once again, shift gears and mention another positive aspect: the film’s engaging animated sequences. Whatever charm Jarrod lacks is somewhat abated by whimsical stop-motion animation that starts at the opening credits and continues throughout the film.

“I love animation,” Cohen says. “It can have more of a powerful effect on the audience than normal dialog-laden scenes. In our case it was more like the Eastern Bloc animation. And I wanted the old school, in-camera kind of stuff.”

Horsley agrees. “You can feel the human in it; that’s what’s lovely about it.”

When asked about all the rotten apples that dominate the animated sequences, Cohen shoots back in his best Groucho Marx: “What is with the rotten apples? I don’t know.”

Horsley offers up a tad more introspection. “When I was a kid,” she says, “I used to feel bad when people would take a bite from an apple and throw it out. I felt like I had an intimate relationship with it. It was gone and it didn’t belong anywhere and it should go home with me.” She stops and let’s out an awkward chortle. When you’re 4 years old you think strange things.”

“Does that mean Jarrod is an apple?”

They’ve obviously been asked this before, as a devilish-looking Cohen responds with “A rotten apple,” to which an equally well-rehearsed Horsley fires back, “Yeah, rotten to the core!”

|

|

Copyright © 2003-2025 Uptown Publications