-

- Episcopal Diocese sues to seize property from bishop

- Same-sex couples hit obstacles obtaining divorces

- Federal appeals court overturns discrimination verdict

- Commission stops short of recommending same-sex marriage

- Democrats eye bill to protect gays

- Polk County files response in same sex marriage case

- National News Briefs

- World News Briefs

feature

Hurts too bad: domestic violence in same-sex relationships

Abuse doesn’t discriminate, but there are resources for help

Published Thursday, 01-May-2008 in issue 1062

Tommy met Ian when he was 17, homeless and living on the streets. The older man took him in, let him stay at his condo, and supplied him with all the crystal meth he wanted. Later he helped Tommy get a job and a driver’s license and buy a car. For Tommy the relationship was the nearest he’d had to a home since his father had thrown him out, and Ian was the first man who’d only wanted to help him. He was grateful.

There were costs, of course.

“I lost my sense of self,” Tommy said. “He was always right and I was always wrong. If I disagreed with him, he’d throw me out.”

As Tommy worked and made money, his self-confidence increased. He made friends and began to develop a life away from Ian. His protégé’s growing independence panicked Ian, who escalated his efforts to control him. He told him what time to come home and which friends he should quit seeing. His criticisms deteriorated into verbal abuse. He’d demand sex whenever he felt like it.

Tommy’s experience is familiar terrain in abusive relationships. National estimates are that one in four intimate partner relationships involve abusive behavior. That estimate includes heterosexual relationships, as well as same sex relationships. Abusive behavior, also called Intimate Partner Violence, does not discriminate based on sexuality, age, culture, social class and income level.

Abuse results in enormous pain and suffering for individuals, and results in larger costs to society in the form of health care, criminal justice costs, lost wages and tax dollars. The Gay & Lesbian Times talked with local therapists, abuse survivors, certified domestic violence counselors, The Center staff members who run a diversion program, and law enforcement staff at the City Attorney’s Family Justice Center to learn how abusive relationships work, and what is happening in San Diego to educate and prevent domestic violence.

In the house of abuse

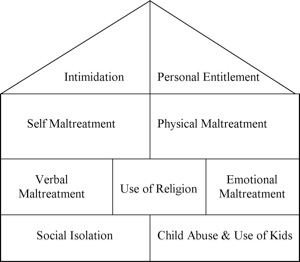

The National Coalition of Anti Violence Programs (NCAVP), an alliance of gay and lesbian anti-violence programs, defines abuse broadly, as “a pattern of behavior in which one partner coerces, dominates and isolates the other to maintain control over the partner.” That definition makes no mention of physical violence. Survivors and professionals know abuse happens in many forms besides shoving and hitting. The diagram titled The House of Abuse, widely used in DV treatment and training programs, uses the metaphor of a house to show the variety of abusive behaviors (see graphic).

The boyfriend who deals with your complaints by cutting up your pictures and throwing your clothes on the floor is an abuser. So is the live-in who demands to know about every call you make and insists that you quit seeing your old friends because she says they’re losers and bad influences. Name-calling and verbal denigration and threats are abusive behavior. The girlfriend who has strict rules about how long a shower you can take and how much of your own money you can spend is an abuser, and so is the one who threatens to go for full custody and tell the judge what a bad parent you are. The partner who says if you leave her she’ll kill herself is as much an abuser as the one who says she’ll kill you.

Every time I was ready to move on, he’d wave the crystal in my face. I’d come back and a week later it was the same old stuff – controlling me, telling me how screwed up I was. – Tommy When a person uses any of these behaviors to control a partner, the relationship has become abusive. As abuse and maltreatment grow in a relationship, the qualities that the partners cherished are the first casualties. Spontaneity and tenderness evaporate, and intimacy withers. Trust dies.

In the same-sex house of abuse, another room

In same-sex relationships the house of abuse has another room: the threat of exposure. An abuser may try to control a partner or keep him from leaving by threatening to out him at work, or to his family. Juan Gonzalez, victims’ services advocate at the Family Justice Center, says he frequently hears of an abusive partner threatening to reveal the victim’s HIV status.

Other aspects of same-sex relationships create their own complications. News of a breakup travels fast in the community. A partner leaving an abusive relationship may fear she’s damaged goods, that no one will want to have anything to do with her, or that if she reports her partner to law enforcement she’ll be ostracized by their friends.

Women more often find themselves more enmeshed in a relationship, says Gonzalez, with possessions and money and pets and space and children shared. Untangling the mesh can be daunting for any couple; when abuse and threats are part of the relationship, it can be even more difficult.

For many men, acknowledging they’re victims flies in the face of a lifetime of socialization that they must always be strong and in control. Doug Braun-Harvey, psychotherapist and director of the Sexual Dependency Institute says that men frequently stay too long in relationships they know are abusive because they can’t bring themselves to acknowledge they are being abused.

Both men and women in abusive relationships bump into common stereotypes. For women, it’s the notion that women couldn’t possibly be violent. For men, it’s the assumption that because they’re both guys and guys are physical, the battering must be mutual. Harvey also notes that some people in the community simply don’t want to acknowledge that abuse and violence happens in GLBTQ relationships, or feel that even if it does, it shouldn’t be talked about, because it gives the community a bad name.

Who are abusers?

Amanda Quayle is a psychologist who’s worked with intimate partner violence for more than 10 years. At The San Diego LGBT Community Center’s behavioral health clinic on El Cajon Boulevard she radiates the enthusiasm and wholesome aura of a benign third grade teacher. “I really like these guys,” she says of the group she runs for male batterers. “They’re people with a terrible set of coping skills to deal with their emotions.”

Quayle explains most abusers were abused as children and/or witnessed abuse. Many have significant difficulties with anger and impulse control, and usually have a history of emotional deprivation and loss as well. They bring these vulnerabilities and a dread of loss to their intimate relationships. A partner’s independence is experienced as a threat of abandonment, giving rise to panic. The controlling and abusive behaviors reflect a desperate and unskillful effort to head off the perceived threat.

The work of education and treatment involves stopping abusive behaviors, learning new skills both for managing feelings and for negotiating in non-abusive ways with a partner. Individual psychotherapy may also focus on resolving painful memories and helping with unfinished business of growing up.

For a small subset of abusers, Quayle’s description doesn’t fit. This group, called vagal reactors, or in the shorthand of treatment professionals, “cobras,” are incapable of feeling empathy for their partners. Their abusive behavior is calculated and deliberately controlling of all interactions with their partners. They have no interest in changing and cannot make use of treatment. Before beginning treatment, whether in a group or in individual therapy, a careful assessment is necessary to determine whether the person can in fact make use of treatment.

The power to end the abuse rests with the survivor

Change happens when the person being abused decides that the situation is no longer tolerable. It’s not an easy decision to come to. Ending the abuse may mean leaving a partner of many years, disrupting a shared history and leaving a shared living arrangement. It may well mean ending the relationship. “Every time I was ready to move on, he’d wave the crystal in my face,” Tommy says. “I’d come back and a week later it was the same old stuff – controlling me, telling me how screwed up I was.”

“Victims stay in violent relationships far too long,” says Gonzalez of the Family Justice Center, the division of the San Diego City Attorney’s office that handles domestic violence cases.

Gonzalez, who was himself once in an abusive relationship, never advises a victim to leave. It’s an extremely difficult decision to come to, one that the victim must make for him or herself. He cites a grim statistic: an abused partner returns to the abusing partner on average nine times before he or she is able to leave for good.

The most dangerous time

When Tommy moved out, Ian panicked. He drove back and forth in front of Tommy’s new building. In e-mails he threatened to hurt Tommy and to expose him for his drug use. Tommy continued to see him until the day a conversation turned sour and Ian grabbed Tommy and threw him to the ground.

Therapists and survivors agree that the most dangerous time in a violent relationship is when the abused partner decides to leave the abuser, which is likely to ramp up all his/her efforts to reel the partner back in and maintain control. There may be threats to out the person, physical violence, including murder, and threats of suicide. Survivors may need to plan carefully in advance of leaving: have a place to go to, change their phone number, etc.

In San Diego people in abusive relationships have an ally in law enforcement. The City Attorney’s office assigns a senior assistant district attorney to oversee all domestic violence prosecutions. At the Family Justice Center (707 Broadway) all the pieces of DV law enforcement are consolidated in a single place: a person can file a complaint, talk with a victim’s advocate, have a forensic medical exam, file for a temporary restraining order, get referrals for temporary shelter, and talk with the attorney handling the case. San Diego Police Department detectives assigned to domestic violence cases have their offices in the same building.

Gina Rippel, the assistant D.A. in charge of the Family Justice Center, holds degrees in law and social work, and is attuned to the complex nature of DV prosecutions. She and victim advocate Gonzalez, a member of the community, work to sensitize attorneys and detectives about the unique situation and needs of GLBTQ violence survivors. Rippel and Gonzalez add that San Diego police officers, the first responders who handle DV complaints, are well trained in dealing with same-sex partner violence. Gonzalez, who is the victim advocate assigned to all same-sex DV cases, says that clients frequently tell him about their surprise at how respectful their treatment has been from the police and prosecutors. “People tell me they didn’t want to call the police because they didn’t know they’d protect [them],” he says. “They’re amazed and they really appreciate it.”

In 1995 California domestic violence law was amended to include same-sex couples. That change required every jurisdiction in the state to develop a treatment program tailored to GLBTQ offenders as an alternative to jail time. The City Attorney’s office approached Braun-Harvey and other therapists in the community asking them to accept referrals from the court for individual therapy. They said no – GLBTQ offenders deserved the same treatment option as straight offenders. They proposed instead that they assist The Center in becoming certified as a treatment provider.

Misdemeanor offenders are offered the choice of three months in jail or participation in The Center’s 52-week group program. Most choose the program. Every applicant is given a thorough psychosocial assessment to determine whether he or she can make use of the program. Men join a men’s group; women join a women’s group. The focus is on learning about abusive behavior and building better skills for handling feelings and relationships.

People in abusive relationships who have not been arrested also seek treatment, often couples therapy. Ellen Stein, Ph.D., a forensic psychologist who treats abusers, usually advises them that couples therapy isn’t a productive approach. Both partners may have issues to work on, but for the abuser, the abusive behavior isn’t something he or she can work on in the partner’s presence.

“For the abuser, the shame about their behavior and the exposure can simply be too much,” Stein says.

Work on abuse issues tends to be more productive in individual therapy, where the focus is on the issues that have given rise to the abuse, including profound dependency needs, extreme sensitivity to loss and a sense of personal vulnerability.

Survival and moving on

Ian’s throwing him down was the last straw for Tommy. He secured a temporary restraining order against his former partner. “Life got dramatically better after that,” Tommy said. “For a few months I was really depressed and lonely, but even then I could see that I was recovering my old self. It’s been a long road.”

A year later, Tommy says he’s staying clear of relationships. He’s not ready, he says, and he doesn’t trust people. “It did me a lot of damage, being with him,” he says. “I’m still working on it.”

For survivors of abusive relationships it may take years to reckon the costs of their abuse and rebuild their lives. Their first effort may be a conversation with Gonzalez, the victim advocate, or with a therapist. The work for survivors starts with deciding what they must do, making a plan that enables them to leave safely, and then the work of grieving the lost relationship, so that they can begin to build the future they want.

|

|

Copyright © 2003-2025 Uptown Publications