-

- Federal marriage law gets first test from Mass.

- New York to use hate crime law in transgender case

- GLAAD frowns upon ‘Bruno’

- College campuses seek balance when views collide

- W. Va. lawmakers get both sides on same-sex marriage

- VA sends letter about unclean equipment

- National News Briefs

- World News Briefs

feature

The Stonewall 40 Project

Looking back on 40 years of San Diego’s Pride movement

Published Thursday, 16-Jul-2009 in issue 1125

When police raided a small gay bar in New York’s Greenwich Village on June 28, 1969, nobody could have predicted that 40 years of activism would result. The raid and the riots that followed were the spark that ignited a firestorm of activism that spread across the country.

Stonewall was the beginning of the modern GLBT Pride movement, and a number of new radical and unapologetic organizations formed in its aftermath. The Gay Liberation Front in New York was one of the first, and independent chapters followed in other cities.

The impact of the Stonewall riots was even felt here in San Diego County, the opposite side of the country, when San Diego State College students formed a local chapter of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), and local activists Robert Brunsting, Ellen Sampson, Harold Luckey and Elizabeth Reid founded The San Diego GLF in early 1970 to promote positive attitudes towards homosexuals.

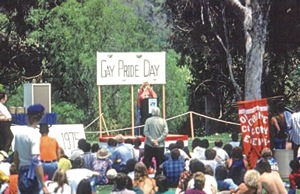

In 1970, organizations across the country were commemorating the Stonewall Riots with what would become the first Pride events. Los Angeles organized the “Christopher Street West” celebration, while San Francisco held a “Gay-In” at Golden Gate Park. The San Diego GLF also hosted a “Gay-In,” although because GLF was largely student run, it held it in December instead of during summer vacation.

That first Gay-In was a small event when compared to today’s Pride celebrations, but the importance of a GLBT group gathering together, in public, in the daytime, to show Pride, can’t be overstated. More than 100 people showed up for the event at Presidio Park, where they posted signs with slogans such as, “I’m gay and I’m OK,” enjoyed food and drinks and celebrated their first big step out of the closet.

The GLF continued to be the most visible representation of Pride in San Diego through the mid 1970s. It hosted political meetings on campus, picketed the police headquarters downtown, attended national and regional conventions with other gay rights organizations and, based on the success of the 1970 Gay-In, hosted similar events in 1971 and 1973.

Locally and nationally the GLF faded from the scene after a few years, as members turned towards less radical organizations with more focused and attainable goals. In San Diego, GLF members diverted their attention toward making a gay community center a reality by founding the Center for Social Services in a house at 2250 B Street.

Finding our Center

The Center immediately became the focus of the community. It gave members of the community a place to go, other than the bars, where they could be themselves, interact with others and get information about services. It also became the political center of the community, the place people went to get informed and get involved. Often, the Center was the place where various ad-hoc committees formed each year to organize Pride festivities.

In 1974, the Center hosted a Gay Pride event at the Center itself. It featured a yard sale and pot-luck dinner, as well as the first Pride march. The marchers didn’t have a permit, so they had to walk along the sidewalk, and many of the participants had to wear paper bags over their heads to protect their identities. The march proceeded to Balboa Park and then adjourned back to the Center where the group congratulated itself on a job well done.

San Diego’s Gay Pride celebration took a giant leap forward in 1975 with an event that included a 400-person march and a rally at Balboa Park. Local attorneys working on behalf of the Center helped to secure a parade permit from the police department and a rally permit from the recreation department.

Although the permits were only secured after much foot dragging by the city, not all members of the city government were ill disposed toward Pride. One notable exception was Councilmember Maureen O’Connor, who sent a telegram of support to the Center. It read: “Good luck, hope the day will bring good friends, good weather, and a successful march.” Years later, O’Connor would become the first mayor to march in the parade.

Save our teachers

For the remainder of the 1970s, Pride continued to be organized by various ad-hoc committees or by special interest groups. For instance, in 1978, Pride was organized by the Save Our Teachers organization, which was the local organization fighting the battle against Proposition 6 – aka the Briggs Initiative, a proposal to ban GLBT teachers from working in California’s public schools.

As the 1970s came to a close, the first attempt at a permanent Pride organization was made. In 1979, the Lesbian and Gay Men’s Pride Alliance (LGMPA) was formed with the intention of creating some continuity so as to avoid re-creating the wheel each year. That year, the organization celebrated the 10th anniversary of the Stonewall riots.

The alliance was short lived however and ended the following year when a split developed within the committee over the direction Pride should take. As often happened in those days, the split was largely along gender lines. Most of the men wanted to change the annual Pride march into a Pride parade, making it less of a political protest and more of a celebration. Many of the women objected to the change, and as a result they left the alliance to form their own organization to found the Dyke march, which subsequently usually took place the week before Pride.

With the dissolution of LGMPA, Doug Moore and other members of the community founded Lambda Pride in 1981, which would be responsible for organizing the Pride events for most of the 1980s.

One of Lambda Pride’s goals was to create an event that would pay for itself and not require pre-event fundraising. Other Pride organizations had held financially successful Pride festivals, and Lambda Pride decided to follow suit. The first Pride festival took place in 1981 on Juniper Street between Fifth and Sixth avenues. Although not the financial success they had hoped for that first year, the community received it well and encouraged Lambda Pride to make it a part of the annual festivities.

Fundies

Religious fundamentalists, or “fundies,” as Pride organizers dubbed them, presented one of the biggest challenges for Pride in the 1980s. Unlike the handful of protesters who attend the parade today, in the 1980s fundies numbered in the hundreds, lining the parade route for many blocks. They posed a volatile threat to the event, and Pride went to extraordinary lengths to avoid any physical confrontations between members of the GLBT community and the fundies.

Lambda Pride focused on passive resistance tactics to diffuse the situation. Its message to the community was that hate feeds on hate. The fundies wanted attention, it said, and the best way to deal with them was to ignore them. “Don’t Feed the Fundies,” signs and flyers Lambda Pride distributed along the parade route pronounced.

For the most part, the tactic was successful. Volunteers known as the Future Former Fundy Fighters, wearing purple sashes, stood between the protesters and the parade contingents and served as a human buffer zone. The only act of violence took place in 1986, when a change in police policy didn’t allow the Fundy Fighters to serve as a buffer zone. As a result, a confrontation occurred between a fundy and a member of a San Francisco contingent.

The fundies began to fade by the end of the decade after their leader, Rev. Dorman Owens was convicted in connection to an attempted abortion clinic bombing. Owens’ conviction deflated the enthusiasm of his followers. It may have also been responsible for the police department’s change in attitude toward Pride. While Pride had tried for years to work with the police to ensure safe events and avoid confrontation, the leader of the opposing group had just been sentenced to 21 months in a federal prison for the attempted bombing.

The final days of Lambda Pride

At the same time Lambda faced an external challenge from the Fundies, it also had internal challenges to face in the form of internal bickering on the board of directors, which led to constant turnover and a lack of communication.

In 1986, Gayzette Editor Christine Kehoe interviewed a Pride representative who told her that the festival that year was going to be “gargantuan,” and Kehoe used that word in an article’s headline. Days after the issue hit the street, Lambda Pride announced that the festival was canceled. Lambda Pride didn’t have the money to put on the event.

Members of the community were outraged. Since its inception, the festival had quickly become one of the community’s favorite events. A town hall meeting was held at the Flame and it was decided that if Lambda Pride wouldn’t have a festival, the community would organize one of its own. At that meeting, a committee was formed and David Manley was nominated to coordinate the event with the help of a $5,000 loan from Chris Shaw, who also offered the parking lot of the West Coast Production Company (WCPC) for the festival location.

Over the next few weekends, community members organized to clear out and clean the WCPC’s dirt parking lot. Trash was hauled away, gravel was brought in, and community members Jeri Dilno and Christine Kehoe both recall pulling weeds and sweeping dirt to prepare for the event.

The event was a success. The festival committee was able to pay back Chris Shaw’s generous loan, and when the books were closed it had a net profit of more than $8,000. The committee made its books public and distributed the funds to community organizations.

As a result of Lambda Pride’s festival failure the previous year, a new board of directors again tried to take the organization in a new direction, led by Bravo magazine publisher Tony Zampella. The “New Lambda Pride” had lofty goals but ultimately fell victim to the same challenges previous boards had faced, and in 1988 Lambda Pride was dissolved.

Its dissolution left the community without a Pride organization for the first time since 1981. However, despite the constant arguing and second guessing within the community over the direction Pride should take, the one thing most people agreed on was that Pride was important. So community activist Albert Bell called for a community meeting at the Center to discuss the creation of an ad hoc Pride committee. From this meeting, Parade Fest ’88 was born.

Parade Fest ’88 was simultaneously both a dismal failure and a huge success. The good news was it spared no expense, paying past-her-prime singer Helen Reddy $5,000 cash to perform five songs; but such expenditures resulted in financial disaster. Parade Fest ’88 ended up $30,000 - $40,000 in debt. Since it had no way of paying, the organization folded with debts to vendors unpaid, leaving the future of San Diego Pride in doubt

15/20 Committee

After years of failures, both organizational and financial, it was time to turn things around. Christine Kehoe and other community members decided it was time to make Pride a more professional organization. The Center provided the seed money and some additional members of the committee, along with the committee, hired the first paid executive director to oversee the event. The strategy was a success; that first year, the committee ended the year more than $20,000 in the black.

Following its success in 1989, the Pride committee became permanent, and the event gradually began to resemble the one we are familiar with today.

After nearly being rained out in 1990, the event was moved from June to the better weather of July. This not only brought sunshine, but meant the event was no longer competing with other Southern California Pride events.

In 1993, the Parade was moved from its route on Fifth and Sixth streets, to the current route that proceeds through the heart of the Gayborhood. The parade was home at last and the new route provided ample viewing space from sidewalks and local businesses.

That same year, the festival was moved to its current location in Marston Point. For years it had been held in the parking lot of the old Naval Hospital, but the rough, uneven surface of the pavement and the lack of shade, combined with swelling attendance made the need for a new festival site critical.

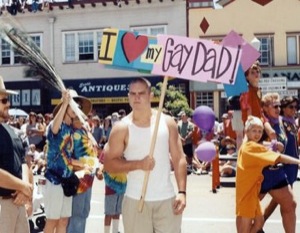

The new date, and the new parade and festival locations, combined to make San Diego Pride a destination event for people from Southern California and beyond, drawing a third of attendees from outside San Diego.

However, one of the big challenges for Pride in the 1990s came from former Mayor Roger Hedgecock and the listeners of his AM radio show. Hedgecock took Pride to court to force it to allow him to march in the parade as part of a “normal people” contingent. He lost the case, and the parade went on as planned, despite a small protest by Hedgecock’s fringe group.

Another challenge for the organization came in 1997, when San Diego resident Andrew Cunanan went on a nationwide killing spree in the months before Pride. Rumors swirled that he would return to town for the occasion, and the national media descended on the city. Barraged with interview requests about the safety plans for the event, new executive director Mandy Schultz experienced trial by fire.

Days before the event, Cunanan was found dead in a Florida marina.

In 1999, a tear-gas canister thrown into the crowd near Tenth and University avenues disrupted the parade, as panicked watchers and participants fled. An arrest was never made.

Pride continued its growth in the 2000s and continued to give back to the community. By 2009, Pride had given more than $1.3 million to local community organizations.

In 2005, Pride came under attack by anti-gay crusader James Hartline, who brought to light that three volunteers and a staff member were registered sex offenders. The attacks created controversy within the community, but at large it supported Pride. Subsequently, Pride became one of the first organizations to perform background checks on volunteers.

The following year, three young men attacked festival goers as they left the grounds. The violence and ferocity of the attacks shocked the community. The police promised swift action, and the ensuing manhunt resulted in the rapid arrest of three suspects and an accomplice.

In the aftermath of Proposition 8’s passage and due to the subsequent surge in community activism, San Diego Pride is celebrating the 40th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots with the theme “Stonewall 2.0 – Activism for Equality.”

The 35th annual parade will take place at 11 a.m. on Saturday, July 18, with 150 contingents. It has become San Diego’s biggest single-day event and attracts 150,000 people each year.

The festival takes place June 18, from noon to 10 p.m. and June 19, from 11 a.m. to 8 p.m. in Balboa Park’s Marston Point. Advance tickets can be purchased at House.Boi (1435 University Ave.) or Mankind (3425 Fifth Ave.), or online from the Pride Web site at: www.sdpridehistory.org, where there is also more information about the rich history of San Diego Pride.

|

|

Copyright © 2003-2026 Uptown Publications