-

- Civil unions go from radical to conservative in four years

- Blacks divided over use of civil rights imagery describing marriage equality

- Gay bishop ready to take over diocese

- Finneran proposes pair of marriage equality ballot questions

- Minnesota Senator says marriage should be redefined

- City council aide blames firing on anti-gay bias

- Activists rally at University of Montana

- National News Briefs

- World News Briefs

national

Blacks divided over use of civil rights imagery describing marriage equality

Rev. Jesse Jackson says comparison is ‘a stretch’

Published Thursday, 11-Mar-2004 in issue 846

RALEIGH, North Carolina (AP) – When small-town Mayor Jason West started presiding over marriages for gays and lesbians, he saw it as nothing short of “the flowering of the largest civil rights movement the country’s had in a generation.”

“The people who would forbid gays from marrying in this country are those who would have made Rosa Parks sit in the back of the bus,” said the Green Party mayor of New Paltz, New York. Parks was the black seamstress whose arrest for refusing to give her bus seat to a white passenger led to the 1955-56 Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott, a turning point in the civil rights movement.

West’s words have a strong resonance for gays and lesbians who feel their rights are being denied, but for blacks who worked to end racial discrimination in the 1950s and ’60s, the reaction is mixed. Some civil rights leaders find the comparison apt, but others call it downright disgraceful.

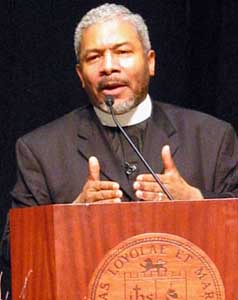

“The gay community is pimping the civil rights movement and the history,” said the Rev. Gene Rivers, a Boston minister and president of the National Ten-Point Leadership Foundation. “In the view of many, it’s racist at worst, cynical at best.”

With marriage equality emerging as the nation’s hot-button social issue, American blacks find themselves being courted as a special ally by both camps. Many are conflicted over attempts to equate the civil disobedience of gay and lesbian unions with still-vivid memories of voting-rights protesters mauled by snarling police dogs and knocked down by firehoses.

Some conservative groups are appealing directly to black congregations to block attempts to co-opt the language of the civil rights movement.

“We oppose attempts to equate homosexuality with civil rights or compare it to benign characteristics such as skin color or place of origin,” says a Web site from the conservative Family Research Council.

Meanwhile, civil rights luminaries such as Julian Bond, board chairman of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and Rep. John Lewis, one of the organizers of the 1963 march on Washington, have spoken on the side of marriage equality. Bond said he supports “gay civil or religious marriage.”

“Discrimination is discrimination – no matter who the victim is, and it is always wrong,” he told The Associated Press. “There are no ‘special rights’ in America, despite the attempts by many to divide blacks and the gay community with the argument that the latter are seeking some imaginary ‘special rights’ at the expense of blacks.”

Lewis filed a friend-of-the-court brief in the Massachusetts case that led to the first unequivocal state ruling recognizing marriage for gays and lesbians.

In its November decision, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court cited the landmark school desegregation case, Brown v. Board of Education. The first marriage licenses for gay and lesbian couples are scheduled to be issued there May 17 – the 50th anniversary of Brown.

The Rev. Joseph Lowery agrees that American blacks should clearly sympathize with the gay and lesbian community’s fight for rights.

But Lowery, who founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference with Martin Luther King Jr., said the sheer weight of U.S. history precludes too close a comparison.

“Homosexuals as people have never been enslaved because of their sexual orientation,” he argued. “They may have been scorned; they may have been discriminated against. But they’ve never been enslaved and declared less than human.”

The Rev. Jesse Jackson, while supporting “equal protection under the law” for gays and lesbians, agreed that comparisons to the struggles of the civil rights movement are “a stretch.”

“Gays were never called three-fifths human in the Constitution,” he said during a recent appearance at Harvard Law School.

Another issue is that of choice, said D’Army Bailey, a marcher with the armed Deacons for Defense and Justice and a founder of the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis.

“I don’t have a choice to be black and, therefore, had to be faced with the human rights battle from birth,” said Bailey, a judge in Memphis.

Keith Boykin, a gay black man, scoffs at the notion that sexual orientation is a choice. But even if it were true, he said, that’s not the point.

“At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter which group is most oppressed or whether they are identically oppressed,” said Boykin, president of the New York-based National Black Justice Coalition. “What matters is that no group be oppressed.”

As a minister, Lowery said he is “in the valley of prayer on the issue of gay marriage.” But, as a black man who was deeply involved in the struggle for equal rights, he is willing to “err on the side of inclusiveness, and not exclusion.”

“I’m going to follow Jesus and say, ‘Whosoever will, let them come,’” he said. “And I’m going to extend rights to all of God’s children. And if I’m wrong, God will have to judge me.”

|

|

Copyright © 2003-2026 Uptown Publications