-

- Assembly committee approves proposal for same-sex marriage

- Same-sex marriage recognized by Oregon judge

- Romney steps up bid to block out-of-state gay couples from marrying

- CA investigators urged to inspect porn industry

- Children of gay parents say they do just fine

- Wisconsin teachers can force students to take HIV tests under new law

- Sharon Stone recognized by lesbian rights group

- National News Briefs

- World News Briefs

feature

Love, borders and the INS

You love someone who’s not an American citizen. You can’t get married. You can’t get a visa. You can’t change citizenship. Is there anything you can you do?

Published Thursday, 29-Apr-2004 in issue 853

If anything is certain about love, it’s that you never know when and where it will strike. This was certainly the case for Jim, who traveled to Mexico in 1993 in order to increase his hiring potential by studying Spanish. Born in Missouri, Jim never expected to find love in the arms of a Mexican man, but that’s exactly what happened.

“I fell in love with the place, the people and the culture,” Jim explains from his current home in San Diego, “but I also fell in love with a Mexican guy, Miguel.” The couple met on January 1, 1993, initiating a long-distance courtship that would last two years. Once they were ready to begin building a life together, Jim and Miguel relocated to Tijuana. Their plan was to remain in Mexico, but cross the border occasionally to see a movie or spend the day in San Diego. However, the couple soon learned how difficult it would be to obtain a visa for Miguel. The relationship became a struggle, and Jim and Miguel separated.

Soon after the couple split up, Miguel met another American man, who not only convinced him to cross the border illegally, but also infected him with the HIV virus. The relationship did not last, and Jim and Miguel later reconciled, this time faced with a relationship with a whole new set of obstacles.

“We’re back together, but Miguel still lives in L.A.,” Jim explains. “We decided it would be better for him there, since San Diego is ringed around by immigration.”

As a binational gay couple facing a legal system that does not recognize their relationship, Jim and Miguel find themselves running out of time, hope and options.

“We really don’t know what to do at this point,” says Jim. “One thing I had really hoped for was for a [female] colleague of mine to marry Miguel. But at a meeting with the national chairperson of Immigration Equality, I asked about that, and learned that if you’ve been here illegally, you can’t use marriage to regularize your status.”

One option the couple is still considering is immigrating to Canada, where Jim could obtain legal status and then sponsor Miguel as his partner. In the meantime, the couple lives in constant fear of deportation and separation.

“In L.A., because of the community, Miguel receives incredible healthcare. Doctors are free, medication is free and therapy is free. He is living in a halfway house that is a wonderful place for people in his situation. But if he were to be deported to Mexico, he would receive absolutely nothing. It’s a concrete, direct risk to life by losing medical care he receives here,” Jim explains.

Binational love: the reality

Unfortunately, Jim and Miguel’s story is far from unique. According to the national, New York-based group Immigration Equality (formerly the Lesbian and Gay Immigration Rights Task Force), the lives of thousands of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and HIV-positive individuals including U.S. citizens, legal residents and immigrants have been adversely impacted by discrimination in U.S. immigration law wherein same-sex couples are denied access to the myriad of rights that protect heterosexual couples in the very same situation. While heterosexual U.S. citizens and permanent residents are able to sponsor their spouses for immigration purposes, same-sex couples are not recognized as “spouses” and are therefore excluded from family-based immigration rights. As a result, a recent study by the Human Rights Campaign estimates that approximately 35,000 GLBT binational couples in the United States currently battle fear, discrimination and possible deportation on a daily basis.

Complicating the issue even further is the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which passed in 1996. According to DOMA, marriage is defined on a federal level as a union between a man and a woman. Because federal law controls immigration, DOMA ensures that GLBT couples that enter into state-approved same-sex unions do not qualify as legally “married” for immigration purposes. Anthony White, San Diego chapter coordinator for Immigration Equality, explains, “You could have marriage in every single state, and you are still not guaranteed immigration rights because DOMA specifically says, for federal purposes, same-sex couples don’t matter.”

Discrimination against same-sex couples under U.S. immigration law is hardly a new phenomenon. Prior to the passage of Congress’ 1990 Immigration Act, the Immigration Naturalization Service (INS) was able to deny citizenship to any individual based solely on his or her sexual orientation. Today, individuals infected with the HIV virus face similarly blatant discriminatory policies. U.S. law bans all HIV-positive persons from entering or immigrating to the United States. A waiver is available to an individual who has a U.S. citizen or permanent resident spouse, parent or child – however, this again excludes same-sex couples that do not qualify legally as “spouses”.

The last resort for many GLBT individuals seeking citizenship is to claim asylum, due to sexual-orientation persecution in their homeland. Under a recent change in the law, however, anyone desiring asylum in the United States must file within one year of arrival here. Because many potential gay and lesbian applicants (and, unfortunately, many immigration attorneys) lack information that sexual orientation-based asylum is possible, relatively few are able to prepare and file a case within that time.

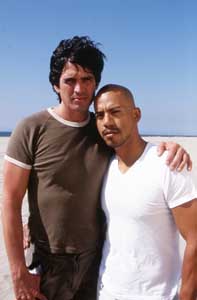

Bill and Carlos

“Before I met Carlos, I thought I had it all. Freedom and free will, financial stability, two careers which afforded me the luxury to unleash my own creativity in how my work was to be executed. What more could I ask for? A relationship would’ve only served to limit me and my pursuits, so why bother?”

Such was the attitude of Bill, a San Diego resident, before he met his life partner and true love, Carlos. As it has a way of doing, love changed everything.

“When I am home, everything reminds me of him and the pain is sometimes too much for me and I fall into a depression.” — Bill, in love with a Mexican citizen “When I met Carlos, he turned my entire world upside down. Before we met, he was able to acquire a tourist visa somehow, so he decided to come see the U.S. When we met, there was a language barrier. We often went to a computer store and used a web-based translation program to converse over coffee. I had realized after a third date that this would be a different experience for me. I arranged to have a translator join us for dinner quite a few times so that we could effectively communicate with each other rather than looking like we were playing parlor games in public. One translator happened to work for an immigration attorney in town, and it was then I learned of our very complicated visa system, in detail.”

With Carlos’ tourist visa approaching expiration, the couple decided to enroll Carlos in English courses and convert his visa to a student visa. After two years of schooling, Carlos’ English was excellent, and the next logical step was to enroll him in college. However, financing a college education on a single-salary budget proved too difficult for the couple, and Carlos decided to return to Mexico in February of 2003.

“Since that time, it has been the most frustrating situation,” explains Bill. “Carlos is now at the age where in Mexico, he is considered too old to be hired. He is only 41. Coming from a poor background, he has no property assets, nor large sums of money in a secret bank account and now, no job. He’s been fortunate enough to move into his mother’s home in Ensenada while he tries to find a way to return, legally. Meanwhile, I continued to scan all of the rules and regulations regarding visas, consult attorneys and seek help from DOS agents who thought they could figure this out. But our situation always came up empty of remedies, much to the surprise of many professionals who may not have been aware of these kinds of cases.”

The couple maintains a long-distance relationship, meeting in Mexico to spend whatever time they can together. “We meet every month in Tijuana. He takes a bus trip up from Ensenada and I drive down to the border and walk across to meet him at a hotel. We have dinner, talk and the next morning I am usually required to return. We stay in touch via email and phone calls,” Bill explains.

The situation continues to take an added emotional toll, leaving both men stranded in their separate worlds. “When I am home, everything reminds me of him and the pain is sometimes too much for me and I fall into a depression,” Bill adds. “I remember one night we were so frustrated that all we could do was hold each other and cry. I know this is the man I want to be with for life. We have a home, we have each other, but we cannot be together.”

Juan

“Here I have a chance. If I go back to Mexico, I don’t have a chance.”

These are the words of Juan, an HIV-positive Mexican national, currently living in San Diego. Juan fell in love with his partner, David, while working for a company in Stanford, Connecticut. When the company moved him back to Mexico, he found it increasingly difficult to return to David. He ended up returning on a tourist visa that expires this August, leaving him with a question of life and death: Does he return to Mexico and lose both his partner and his medical care, or remain in the United States illegally?

“Gay people can have relationships that are as strong as straight couples’,” says Juan. “We are not different. We all have the same problems. My partner and I love each other very much, and it is not fair that we don’t have the same rights. We are forced to deal with many problems [due to our sexuality] and in some cases, these are decisions between life and death, and that’s not fair.”

Fighting back: the Permanent Partners Immigration Act

“The laws that exist in INS will not apply to LGBT couples because it’s discriminatory, it’s heinous, it’s awful – it leaves us out,” explains John Nechman, co-chair of Immigration Equality. Nechman spoke to the Gay & Lesbian Times during a recent visit to San Diego. “So we have to come up with creative ways to keep couples here, and we have to do so with an organization that is the most monstrous of all. This is an organization that has been given the power to read minds, and that’s a very dangerous power to give any organization. They get to decide, when you’re coming across the border, if you’re intending to stay or if you’re intending to return to your home country.”

Nechman is one of the nation’s top spokespersons on the subject of immigration equality. After beginning his law career as a criminal defense lawyer in Houston, he left his prestigious law firm in order to start his own immigration-based practice. To date, most of Nechman’s clients are GLBT couples in need of immigration assistance, a cause that is very close to his own heart, since Nechman himself is involved in a binational, gay relationship.

“I fell in love with a Columbian,” Nechman explains. “I didn’t know he was Columbian at the time. I mean, you don’t go up to someone and say, ‘Can you show me you’re legal before we date?’ You don’t ask someone to show their visa. So there’s no question that at the time, I never even considered all the issues at play for couples in this situation. Immediately, it was obvious to us that, although my partner was a student, eventually his visa was going to end. And we needed to figure out a way for him to stay, because I didn’t want to go live in Columbia.”

On the forefront of Nechman’s political agenda is raising awareness around the Permanent Partners Immigration Act (PPIA), a bill that will allow U.S. citizens and permanent residents to sponsor their same-sex partners for immigration to the United States. The PPIA would simply extend to same-sex couples the same immigration rights enjoyed by legal spouses. Currently, 15 countries recognize lesbian and gay couples for the purposes of immigration: Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Israel, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Passage of PPIA would bring the United States one step closer to joining the list of nations who already support immigration equality for GLBT people.

“Under PPIA, we would be put through the same ringer as any married couple. We’d have to show the same proof of permanence of relationship, and so on,” explains Nechman. In fact, passage of PPIA would provide GLBT individuals with no special rights whatsoever. “The whole issue of PPIA is to come up with something that circumvents DOMA. Because of the recognition that as long as it’s in place, as long as it is a congressional enactment, the chances of it being knocked out is very low,” says Nechman.

Nechman explains that when PPIA was first introduced, critics claimed that it had “an ice-cube’s chance in hell” of passing. Luckily, this may not be the case. “Right now, PPIA sits at 122 co-sponsors, with bipartisan support in the House, and 12 co-sponsors and bipartisan support in the Senate. It’s the number-one most co-sponsored of any immigration bill in Congress right now, which shocks people,” explains Nechman.

“Of course, it’s not where it needs to be to go the floor, but it’s not going to go there now with the Republicans in powe2,” adds Nechman. “If we get the numbers changed in Congress, it will be the first thing to go to the floor. And with the way things are going for the Republicans right now, it’s not a completely far-fetched idea.”

Another vital organization currently on board in the fight for PPIA is the Human Rights Campaign (HRC). Each year, the HRC scores legislators based on how they vote on GLBT issues, with a score of 100 percent meaning that an individual has voted across the board in support of GLBT equality. Upping the ante this year, HRC has taken on PPIA as one of its issues. From now on, in order for a legislator to receive a score of 100 percent, he or she will have to vote in support of PPIA, a notion that raises enthusiasm amongst activists and binational couples alike.

Most importantly, support of PPIA could also aid activists in the fight against a potential constitutional amendment to ban same-sex marriage. “To kill the federal marriage amendment, we’d need about 167 votes against it. However, if we get 167 sponsors of PPIA, how could they possibly sponsor PPIA and the marriage amendment?” questions Nechman, who is invigorated by the possibility. “Once we surpass that, I think we can say that this legislation alone has now all but assured the failure of this pathetic effort to codify discrimination within our nation’s most sacred law.”

One step forward, two steps back: the dangers of state marriage

Placing PPIA aside, many binational couples are still curious as to how marriage advancements in places like San Francisco or New York affect the battle for immigration equality. Unfortunately, immigration activists agree that binational GLBT couples must be wary of entering into state civil unions, no matter how legal they may appear to be.

“There is no more pertinent issue with regards to marriage equality than the breakup of couples that are committed, that have been here together forever, that are absolutely in love, and want to spend their lives together,” says Nechman. “The sad reality, however, is that with all the euphoria in San Francisco, where we have one of our most active chapters, we had to put a warning on the website, because to our couples, [marriage] won’t help them. In fact, it could be more harmful to them.”

Again, many of the problems related to legal civil-unions have to do with “intent” under the law. “If they go and marry, when that person goes to apply for an adjustment of status or a new F1 visa, there is going to be a question as to whether he is married. And if he puts down no, he has just committed fraud. If he puts down yes, they’re going to want to know info about the spouse; and if he’s applying for a new F1, that means temporary intent. By putting down a U.S. spouse, that means that you’re intending to stay,” explains Nechman.

Nechman admits that he is forced to tell couples that no matter how safe a foreign partner may appear to be, there is no guarantee that state marriage will be a safe option. “I can come up with a scenario for almost any couple that could put them into jeopardy if they go and marry,” he says solemnly. “Sometimes the INS does the ugliest things.”

Alison and Mary

“The immigration process has impacted our lives in different ways,” explains Mary, an American citizen currently in a loving, binational relationship of five years. Her partner Alison, born a Canadian citizen, is suffering through the process of obtaining permanent U.S. residency. In 2002, Alison, an RN, signed on with her employer full time and has subsequently been sponsored by them for “green card” status. The application for permanent residency was filed in May 2002; however, the process is ongoing and arduous, requiring many trips to varying immigration offices. At this point, the couple’s attorney estimates that Alison’s application will be reviewed in about one year to determine eligibility for permanent employment status. Until that time, the couple sits and waits.

The immigration process continues to affect Alison and Mary both financially and emotionally.

“Alison is attending school for a graduate degree in addition to working full time,” says Mary. “When she initially applied, she could not get resident status [though she had been here for three years at the time] and was going to be forced to pay three times the tuition due to her status as a foreign student. She had to postpone her education due to an inability to pay the higher costs. Alison now attends the University of San Diego, which is a private school and subsequently does not differentiate between residents and non-residents for tuition purposes.”

Immigration status has also affected the couple’s ability to start a family.

“Our plan is for Alison to carry [our] child. However, in order to retain her temporary employment status, Alison is required to work full time,” says Mary. “Obviously, this would not be possible if she was to become pregnant and deliver a child. Due to this fact, we feel that we need to wait until Alison has permanent residence status. Alison is now 40 and we believe that the delay in the immigration process may eventually impact our ability to conceive.”

Mary adds that the couple is afraid to commit to one another on paper, out of fear that such an action will jeopardize Alison’s immigration status. “We also want to protect ourselves within our relationship to the full extent of the law and would like to register as domestic partners. However, we are hesitant to complete any paperwork identifying us as a ‘couple’ in case it should fall into the hands of a homophobic immigration official,” says Mary. “We are not sure of the extent to which the law can realistically bar entry to the country based on sexual orientation, but we are fully aware of the potential impact that one homophobic official could have on Alison’s case. So, at this point, we each have a will, but no other legal protections for our respective estates.”

Mary and Alison are urging all members of the GLBT community to get involved with the fight for immigration equality, regardless of whether it effects them on a personal basis. “Our request to the rest of the LGBT community is to not think of this as someone else’s problem,” Mary and Alison wrote in an e mail. “Talk to your families, your friends, your co-workers to garner support for same-sex immigration rights, so that if and when it becomes a ballot issue, the support is there to get it passed.”

“The laws that exist in INS will not apply to LGBT couples because it’s discriminatory, it’s heinous, it’s awful – it leaves us out.” — John Nechman, co-chair of the New York-based Immigration Equality What are you waiting for? Do something!

GLBT binational couples in San Diego and worldwide need your help. Unrecognizable under our nation’s immigration laws, these loving, committed couples are forced to come out of two closets: the gay closet and the immigration closet. You can do your part to help them by writing to your legislators, attending local meetings and speaking with everyone you know about the bigotry built into our nation’s immigration policies.

“There is so much ignorance about this. I’m sure that there’s much I’m ignorant on still,” comments Jim of San Diego, as he waits to hear any bit of good news in regards to being reunited with his partner. “But communication, mutual knowledge, mutual sympathy, even when it’s not problems we share, it’s really important. If it’s not that, it’s not really community.”

Those interviewed for this story requested that their last names be withheld. Some interviews were conducted by e-mail.

|

|

Copyright © 2003-2026 Uptown Publications