-

- Colorado group launches GLBT advocacy ads

- Same-sex couples in Tampa, Orlando sue to challenge state marriage ban

- Group’s activities stir controversy over pastors’ politics

- Unlikely activists: ACLU draws diverse group for lawsuit

- Senior couples not quick to register as domestic partners

- Judge orders New York police department to rethink AIDS disability

- National News Briefs

- World News Briefs

feature

Superheroes and the feminine mystique

Published Thursday, 22-Jul-2004 in issue 865

Bulletproof bracelets, bionics and Farrah hair. Warrior princesses, vampire slayers and super spies. Are female superheroes the new divas?

Why do gay men love larger-than-life women? Why do lesbians love Sydney Bristow and Xena? The Gay & Lesbian Times got in touch with some comic creators and got into the minds of our favorite comics in an attempt to analyze the superhero mystique.

These larger-than-life women wear fabulous outfits, are strong and powerful, fight for the general good and men everywhere love (and fear) them. Is it any wonder that a generation of gay men have idolized these divas in the same way that previous generations have identified with Bette Davis, Joan Crawford and Judy Garland? There aren’t many gay men who lived through the ’70s or reruns of the hit television show in syndication through the ’80s and ’90s who can’t sing the theme song to “Wonder Woman”. Similarly, there is a fascination with characters like Jamie Sommers/the Bionic Woman, “Charlie’s Angels” and, more recently, Xena, “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” and Sydney Bristow of “Alias”.

These larger-than-life women wear fabulous outfits, are strong and powerful, fight for the general good and men everywhere love (and fear) them. Is it any wonder that a generation of gay men have idolized these divas in the same way that previous generations have identified with Bette Davis, Joan Crawford and Judy Garland?

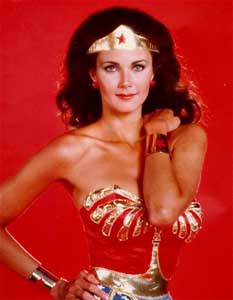

Phil Jimenez has made a career out of his idolization of super-divas. A child of the ’70s, Jimenez grew up watching the “Wonder Woman” television series that starred Lynda Carter. After moving to New York to pursue a career as an artist, Jimenez found himself working for DC Comics, drawing and eventually writing for the “Wonder Woman” comic book. Jimenez is widely considered to be one of the experts on the modern-day version of the character, and he’s a fan – with an encyclopedic knowledge – of many of these super-divas.

“My theory always remains that these women were both super strong and they were sex symbols to men,” Jimenez says, in explanation of male fascination with these super-divas. “I think for a lot of young gay men, at least for me, what appealed to them was that they were super heroic – they did these heroic feats, they went to fantastic worlds, they fought these super villains. So that was appealing on one level. On the other level, they were also sexually desirable to men, which I think, when you’re young and you’re into men but you don’t know how or why, I think that’s a very appealing quality, because not only are you saving the world, but cute boys want you all along the way.”

Of course earning a place in the pantheon of ’70s superhero divas were characters like the incredibly strong Bionic Woman and the women of “Charlie’s Angels” who, even though they did not possess fantastic super powers, are indeed heroes in their own right.

“If your exploits become larger than life, when they are so outrageous or over the top – I tend to think that’s when it becomes super-heroic as opposed to simple heroism,” Jimenez says, offering up his definition of a super hero.

Xena’s ’90s feminism is a form of far more aggressive feminism, kind of like … ‘If men can do it, so will we. We can kick your ass,’ as opposed to the softer … ‘can’t we all just get along’ kind of feminism of the ’70s. The strong female leads have also traditionally captured the attention of the lesbian community, notably the book smart Sabrina played by Kate Jackson on “Charlie’s Angels”, one of the first breakout hits to feature a group of female leads taking on criminals without bulletproof bracelets or bionics.

“I think that on ‘Charlie’s Angels’ Kate Jackson was generally the one that all the dykes either dug or wanted to be,” says Joan Hilty, an out editor at DC Comics who handles titles from their children’s line as well as superhero titles like Birds of Prey and the upcoming Manhunter series. “Super heroes, in terms of a lesbian following … I think lesbian icons in movies and TV were a little more common in the ’70s and it’s a little more common to have them in comics now. I think that the current incarnation of Cat Woman is definitely one. Yes, definitely, you have always been able to find the lesbian sort of adventure heroes in pop culture, but I would say that it was only recently that it has become that common in comics.”

The super-divas of the ’70s also brought with them a new perspective on fighting crime and super-villains that were motivated by the decade’s post-feminist era. “Wonder Woman” in particular provides an unusual perspective on a male-dominated world. The character of Wonder Woman was born Princess Diana on Paradise Island, a society of Amazon women where “mankind’s” wars and fighting impeded the evolution of science and philosophy. She originally came to America to help fight the Nazis during World War II, using the secret identity of Diana Prince to work for the military; but beyond fighting evil, she also came to teach the values of peace, truth and love.

“‘Wonder Woman’, particularly, that first season, is about not what idiots men are,” says Jimenez, “but how violent and how destructive they are and sort of how Diana, the whole season, especially when Debra Winger comes in as Wonder Girl, they are perplexed by these choices that men make and they think it’s sort of laughable. There was a real sort of post-feminist edge.”

One of the key elements that GLBT fans can identify with is the fact that Wonder Woman didn’t feel the need to match up to a man, or even fit into man’s world. She existed in a world outside of the norm, and this was as much a part of her strength as her magical lasso and bulletproof bracelets.

“It was very peace oriented,” Jimenez says. “I think the producers in the ’70s took advantage essentially of the inherent femininity of … actresses like Lindsey Wagner and Lynda Carter. They really played that up. Neither of them were out bashing the villains; they were either defensive warriors or, in Wonder Woman’s case, oftentimes showing men the absurdity of their behavior.”

‘Buffy’ is a comic book come to life: You have a lead character with super powers chosen for a special destiny. How many gay people wish that were true, or feel that is true for them? In one exchange from the show’s first season, Wonder Woman has a conversation with a female co-worker in the War Department about some of her goals and aspirations.

“I’m sorry Diana, but you’re not a man,” her co-worker says, criticizing her independent thinking. Wonder Woman, in the guise of Diana Prince responds, “I know – it’s something I have always been thankful for.”

Jimenez draws his own message from the show and the time in which it was written: “You’re not here to be men, you’re here to show men that there is a different way of thinking. This is the ’70s angle and I think it was a feminist thing. You’re pointing out the flaws of the maleness of the world around you, whereas now the female characters tend to more aggressive. … They have become essentially female versions of the male characters, as opposed to women who are also investigators or also crime fighters.”

While the ranks of female heroes in the ’70s swelled to include characters like Isis, Electra Woman and Dyna Girl, along with a revolving door of Angels who would eventually replace Farrah Fawcett and Jacquelyn Smith, the popularity of these female heroes eventually died out and the series were all but gone by the 1980s. In fact, moving into the ’80s, it seemed as though the super-divas were facing extinction.

“I wonder if that’s a reflection of the Reagan ’80s, sort of a more aggressive, Cold War time period,” Jimenez says. “That was also a time of Rambo, First Blood, Terminator and all of these sort of hard-core male-dominated, gun-dominated action pictures.”

It wasn’t until 1994, with the introduction of “Xena, the Warrior Princess”, who battled mythical beasts and barbarians, that super-diva GLBTs could love returned to the small screen in full form.

“She definitely has a lesbian following,” says Jimenez. “I think that’s partly because she’s a physically more aggressive character and I think for many women that’s exciting, and exhilarating. … I’m not a woman, so I am talking out of turn, but to see a woman who is so aggressive and kick-ass … and as pretty as Lucy Lawless was, she wasn’t overly sexy in the way that Lynda Carter was in that Wonder Woman outfit. She’s more of a barbarian, so I don’t think she was sexualized in quite the same way. All of the people I know who watched the show thought Gabriel was the hot one. She’s the cute blond with abs of steel, and was probably more approachable and accessible. Xena was never really approachable.”

He adds that the evolution of Xena as a hero was a sign of the times: “The feminism is what it needs to be for that time period. Xena’s ’90s feminism is a form of far more aggressive feminism, kind of like … ‘If men can do it so will we. We can kick your ass’ as opposed to the softer ’70s feminism, the equal rights and ‘can’t we all just get along’ kind of feminism of the ’70s.”

This kind of changing culture has even had an affect on how Wonder Woman is portrayed in comics.

“I had this debate over whether Wonder Woman should beat up or kill her foes,” Jimenez says. “I had this gay guy come up and tell me he couldn’t wait to see Wonder Woman beat the shit out of people because he was this poor bullied kid in his school and he was bullied for being gay, and comic books, particularly Wonder Woman, was the one place where he could see heroes actually beat the bad guys – and that has always stuck with me, that he needed to see his female heroes, especially Wonder Woman, beat up people.”

Jimenez says that his own personal, softer image of Wonder Woman had an influence on how he portrayed her as a character, despite the emerging trend of more aggressive and violent characters.

“My needs and what I got out of her as a young gay person were obviously different from the needs of this gay person who needed a much more revenge-filled comic to sort of invest in,” he says.

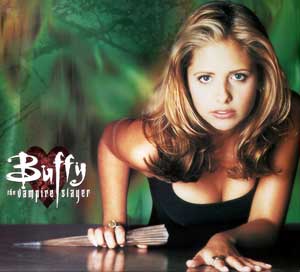

In the late ’90s a synthesis of the female superheroes began to take place, drawing on the aggressive strength and power of characters like Xena, but still secure and feminine like those of the ’70s. The first pop culture example of this came in the form of Joss Whedon’s “Buffy the Vampire Slayer”, loosely based on the comic film of the same name from the early ’90s.

“‘Buffy’ was very cool because I thought what Joss did was actually really incredible,” Jimenez says. “They start her out in high school, which is huge. It’s very comic-book-like. … ‘Buffy’ is a comic book come to life: You have a lead character with super powers chosen for a special destiny. How many gay people wish that were true, or feel that is true for them?”

What “Buffy” also managed to do was work in themes that were relevant to the lives of its fan base, both gay and straight. While the show was praised for its positive portrayal of the lesbian couple Willow and Tara, it also featured characters who dealt with issues like coming out. In one episode during the show’s second season, a werewolf terrorized the high school and, when confronted about hiding a secret, one high school jock was forced to come out as gay. His classmates accepted him, while another character felt he had to stay in the closet because he would never be accepted as a werewolf (though he was eventually accepted).

Hilty says she appreciates how the show “uses teenager-hood, the way it uses horror as a metaphor for being a teenager, and does it so effectively with such strong female characters. Women … are essentially running the show, who fight their own battles, who don’t need to be rescued and who are young women you would actually want to hang around with in real life.”

Jimenez adds: “It seems to me that the current evolution is a synthesis of that kind of kick-ass mentality of ‘I can fuck with you. I can kick your teeth out three ways to Sunday and I can kill you seven different ways’ and yet somehow blending that with femininity and sexuality, and I think that’s sort of the perfect synthesized goal on some level. For me it’s why I think ‘Charlie’s Angels’ works so well in its current incarnation. What appeals to me about those characters [is] underneath all of it they are all incredibly smart, well trained, gifted, intelligent women who can kick the shit out of you, but are also very sexy and fun.”

The latest character to join the superhero diva pantheon is “Alias” heroine Sydney Bristow, an average college student who travels the globe donning fabulous disguises as a secret agent for the CIA. Like the other women who have captured a GLBT following, the balance of Bristow’s secret agent life and social life make her a character that is accessible on some level to the average GLBT.

“I suspect that, as with ‘Buffy the Vampire Slayer’, you’ve got a show that’s got a great metaphor,” Hilty says. “It’s a fantasy-slash-adventure show that is at its heart a metaphor for growing up in confusing circumstances. In ‘Buffy’, it’s being a chosen one who sticks out from the crowd. With ‘Alias’, it’s not having control of your past or future.”

All these shows have well-written, three-dimensional characters that GLBTs can invest in and identify with.

“I think for gay people … a strong female lead is an easier archetype to identify with on some level,” Jimenez says. “This is Pop Psychology 101 for me, but, going back to the Wonder Woman thing, you can project on a female a lot easier than you can on a straight guy like Rambo because her interests are going to be more like yours and she’s going to be an object of sexual desire – and I think it all comes back down to that on some level.”

Hilty adds that GLBT readers are also critical about their choices for entertainment.

“I think gay readers can tell the difference between a strong female character [who is] genuinely interesting and is strong and heroic and a strong female character who is just basically boobs and an AK-47,” she says. “You’ve got to be careful with that. When you say ‘strong female character’ there have been a lot of classless shots at that type thrown out there that’s marketed more to straight guys. I think gay readers make that distinction.”

|

|

Copyright © 2003-2025 Uptown Publications