-

- House passes Marriage Protection Act

- Largest ever GLBT delegation attends Democratic National Convention

- Court: Floridians who have sex changes can’t marry as new gender

- Cho flap mars Unity at Democratic National Convention

- Southern Democrats buck party by opposing same-sex marriage

- National News Briefs

- World News Briefs

-

- Profiles in passion

- Grand Marshall: Nicole on presidents, priests and parades

- Lifetime Achievement Award: Dr. Al Best and Eduardo Moncada march to the front

- Champion of Pride: Pat Washington gets political

- Champion of Pride: Marci Bair is selfishness in the most selfless way

- Friend of Pride: Gracia Molina de Pick – radical politics may just be genetic

- Friend of Pride: Linda Bridges Pennington looks over the fence

- Community Service Award: Kevin Tilden loves winning — other people winning, that is …

- Community Service Award: Amanda Nicole Watson lives her truth

- Pearl of Pride: The San Diego LGBT Community Center

- Stonewall Service Award: Update

- Change is coming

feature

From paper bags to rainbow flags

Happy 30th, San Diego Pride

Published Thursday, 29-Jul-2004 in issue 866

Ask anyone who attended San Diego’s first official Pride march in 1974 what he or she remembers from that momentous day, and most will give you a simple answer – paper bags. They are not referring to shopping bags or lunch bags or any other bag used in its traditional sense, but are instead recalling the numerous individuals who marched bravely in San Diego’s first civil disobedience march with paper bags over their heads, forced to conceal their identities as GLBT citizens of San Diego.

“What I always recall is that some of the people showed up with paper bags over their heads, with the eyes cut out,” explains local activist Nicole Murray-Ramirez. Murray-Ramirez, who is being honored as this year’s San Diego LGBT Pride Grand Marshall (and who is a writer for this paper), was one of three original organizers of the 1974 march, and the only one still living. (Jess Jessop and Tom Homann have passed away, but are commemorated in The Center’s new Wall of Honor exhibit.)

“They were the ‘unknown gays,’ as we called them, and a lot had jobs,” says Murray-Ramirez of the early participants. “A lot were military. A lot of people had said that myself and others were brave [for participating], but I don’t think I was brave because I was already out. I think the brave and the heroes of that day were those who had jobs – even those with the bags. They were the ones who marched knowing they could lose everything.”

“A homosexual parade? We don’t issue permits for that.” -A city policeman to Nicole Murray-Ramirez, in 1974, after Murray-Ramirez requested a permit for what was to become the first-ever San Diego Pride parade. It took place that year without the permit. In a city that has become one of the country’s top destinations for celebrating GLBT Pride, drawing numbers well into the hundreds of thousands each year, it is difficult to imagine that San Diego was once far from being considered “gay friendly.” A quick look back through history, however, proves that building a GLBT community in a notoriously Republican city was quite an undertaking.

“I remember that those early years were very difficult years. It was illegal to be gay, illegal to be in drag,” says Murray-Ramirez. “If you ever would have told me there would be 150,000 people marching [in the San Diego Pride parade], along with the chief of police and the mayor, I never would have believed you. These are great changes, and are the progress and testimony of a community who refused to go away, refused to stay in the closet, of people who said, ‘We are going to take our rightful place and help build this city into what we believe to be America’s finest city.’”

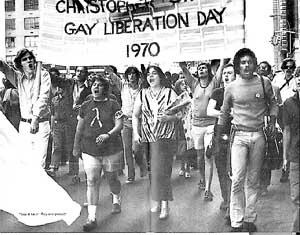

Takin’ it to the street on Christopher Street

Five years before Murray-Ramirez and a small group of San Diego activists organized their 1974 San Diego march, a political pressure valve burst in New York City.

During the last weekend of June of 1969, police and Alcoholic Beverage Control Board agents entered a gay bar, The Stonewall Inn, on Christopher Street. Claiming that they were on the premises to bust the Stonewall for serving liquor without a license, the officers entered the bar and began making the standard, homophobic comments. The raid was followed by police action to remove all patrons for the bar, and news reports from the time wrote that Stonewall’s patrons were lined up outside the bar while the police began to check ID. At some point, patrons began throwing objects and a riot broke out. Street kids, drag queens, students and other patrons began what would go down in history as one of the most famous, three-day-long, civil rights rebellions – the Stonewall rebellion of 1969. With Stonewall, the GLBT civil rights movement took form and slogans like “gay power” rang out on New York City’s streets. Out of Stonewall came the Gay Liberation Front, which was organized and visible within a year. The repercussions were felt worldwide, and the anniversary of Stonewall, now in its 35th year, is celebrated annually along with Pride celebrations worldwide.

But with the comforts of increasing visibility and civil rights, many activists fear that our community’s collective historical memory dulls.

“For the first time, after countless years of oppression, the GLBT civil rights movement took form, and slogans like ‘gay power’ rang out on New York City’s streets. The repercussions were felt worldwide.” “I’m a little concerned that [the original meaning of Pride] has been lost,” says civil-rights attorney Bridget Wilson who has been a San Diego activist since 1972. “There are tons of people who don’t understand why we do this. The original reason was to celebrate Christopher Street Day, and to talk to people and remind people. That was the way Pride was framed for years, into the mid ’80s – as a commemoration of Stonewall. In those days, people were gay liberationists. Now it’s a revolving circuit party, on some levels.”

Murray-Ramirez agrees that amidst this year’s celebration, both reflection and remembrance must play an integral role. “This is a 30-year celebration of the GLBT community, and we’ve got to remember how we got here, who our trailblazers were. If anything, we must remember those people who helped bring this community to where we are today.”

A homosexual parade?

In 1974, San Diego GLBT activists resisted the bigotry of the time and, with Stonewall-level bravery, began planning for what would become San Diego’s first Pride demonstration.

“One of the things you have to remember is that the first few parades were carried out when sex between same-sex partners was still a crime,” says Wilson. “You’re talking about people who, to doctors, were sick and, to police, were criminals. Back then, the only openly gay people you met were involved in the sex business and in bars – and it was really not until the early ’80s [that] we could get a parade permit without a legal battle.”

As one of the first activists to attempt getting a permit for the march, Murray-Ramirez remembers the struggle involved with the city. One policeman responded to the permit request with, “A homosexual parade? We don’t issue permits for that.” In order for early activists to obtain permits for Pride in the early years, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) was contacted, and a lawsuit was threatened against the City of San Diego. The city, in turn, backed down, but not without their share of resentment.

“If you are gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender, the most important day of your life is not your birthday – it is Election Day.” “I can remember that when we went to pick one permit up, the officer said, ‘We cannot guarantee your safety.’ You’ve got to remember that, at that time, this was a very conservative city that always went Republican,” says Murray-Ramirez.

Former executive director of The Center, Jeri Dilno arrived in San Diego in 1975 to discover that the San Diego Police Department did not even have a civil disobedience department. “Most cities had experienced a big, political march of some kind [by that time], but San Diego was always a little behind politically,” explains Dilno. “The issue was that they did not have any kind of process for protecting people in a civil disobedience or protest march.”

Despite permit issues, and a general insecurity as to how many people would actually show up to protest, the pioneers of San Diego’s GLBT civil rights movement continued with their plans to raise the visibility of their community.

For the first Pride demonstration, about 200 individuals met at Hobo Park (then at India and G streets), some wearing bags on their heads, some visible for all to see. They marched downtown on a Sunday, at a time when the area was extremely military on the weekends, dodging slurs and cat-calls as they walked. The march commenced in Balboa Park with a rally.

“The turnout on the streets was never big because so many people were in the closet,” recounts Murray-Ramirez. “At that time in San Diego, there was a lot of police harassment. The police department was very racist and homophobic, and they were not happy [with plans for the Pride march]. The politicians stayed away from us, the mayor refused to meet with us. The marching contingent was mostly made up of bars and such, because we didn’t have many gay organizations.

“As a person who lived in this city when the police would beat us down, raid our bars, arrest us for lewd conduct – to see where we are today is a true profile in courage.”

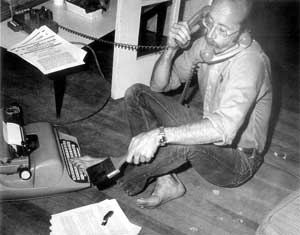

Jess Jessop, one of the original organizers of San Diego Pride, in 1973 Change is in the air

“When we showed up for the first few Pride events, you weren’t sure if you were going to be arrested or attacked,” says Wilson. “Over the years, things have diligently grown.”

Change became evident just one year after the first demonstration when in 1975, according to Dilno, more than 1,000 people attended the Pride rally. “We had a platform, some big speakers, a podium, and a portable mic,” she says. “And the rally ended with everyone spontaneously singing, ‘We Shall Overcome,’ which was the movement song of the era. It was a very moving, intimate experience.”

For many years, Pride remained an ever-changing, transitional event, with little formal organization. Rallies took place in parks and parking lots around the city. And in 1989 local activists began discussing ways to form into a more structured organization. According to Dilno, it was a local activist named Doug Moore who “took the bull by the horns” and formed a committee of 12 to oversee the planning of the event. And in that first year, the first executive director of Pride, Tim Williams, was hired. San Diego Pride formed as a sub-group of The Center, with plans to emancipate themselves into an independent organization within five years.

Change continued to take place, in many forms, over the next few years. After June Pride festivities were almost rained out in 1990 and 1991, the Pride committee decided to move Pride to the month of July.

Just four years into its five-year organizational plan, San Diego Pride was challenged by Robert Hedgecock and his band of “normal people” from the right to let the anti-gay group participate in the Pride parade. Hedgecock argued that it was unfair for the GLBT community to hold a parade when “normal people” didn’t have one as well. He wanted the right to march, despite his bigoted views on gays and lesbians. In order to prevent Hedgecock and the “normal people” from participating in the march, the ACLU aided San Diego Pride in adding a clause to their participant contract, stating that all marchers must support the aims and goals of San Diego Pride, as well as the fight for GLBT civil rights. When Hedgecock refused to sign the contract, he was banned from participating in the march. But due to legal issues involved with the case, San Diego Pride decided it was best to split from The Center at that time and become its own organization. Since then, San Diego Pride has flourished as its own entity, and now puts on the biggest civic event in San Diego.

Pride, pride, and more pride

“When my partner and I moved to San Diego in 1996, we arrived on the tails of Pride weekend,” remembers Pat Washington, a scholar and activist who is being honored as a Champion of Pride for this year’s celebrations. “We drove cross-country from the East Coast, and when we got here, there were Pride flags everywhere. We thought we had landed in a city where they celebrated Pride every day, because we didn’t know Pride had just passed! But it really did make us feel that we were coming to a place where being out and being visible were part of everyday life. Of course, it didn’t take us long to see that there are pockets of San Diego that still leave room for improvement.”

In the early ’90s Washington found herself in a compromising position when a Midwestern university hired her, assuming that she was a straight, African-American woman. Since then, she explains, she makes a point to always be upfront about her sexual identity.

“For me, over the years, my visibility and my outness as a lesbian has been a fairly new phenomenon for me, but a conscious choice,” she explains. “People assume that I’m straight, so I have the privilege and the luxury of telling people that I’m a lesbian. It’s something I now feel compelled to do.”

Washington also feels compelled to participate in San Diego Pride, despite hesitations that she harbored in the past. “I used to not go to parades, rallies or marches because I believed they were too commercial,” she says. “I have since changed my view, after being in San Diego where [the movement] truly is about politics and equality. What’s been done, what needs to be done – it all comes together here. I’m lucky that I discovered Pride in San Diego.”

When Washington reflects on the history of Pride, she remembers her true heroes of Stonewall – the black and Latino street kids who risked their lives in 1969, in order to forward the gay rights movement. She brings their fire to her quest for civil equality.

Here in San Diego, our own youth army is busy making Pride accessible to the youth community as well. San Diego Pride now provides youth with their own stage on the Pride grounds, creating an area that is accessible and welcoming to younger GLBT community members.

“I have been the coordinator for the Youth Xone area for the past three years,” explains Pride enthusiast Ren Petty, who also served as director of the second annual Youth Pride celebration in May. “It has been great to watch the space grow in both size and youth interest. I didn’t really choose the cause – it chose me. I meet new young people each year who are just coming terms with their sexuality, and being able to help them and be a friend they can rely on is its own reward.”

Petty has witnessed many incredible moments at San Diego Pride, but one experience in particular stands out. “A few years back the parade was tear-gassed. I was the parade marshal for the community’s youth float, which had more than 50 youth riding a flatbed truck,” she recalls. “A gas bomb went off a few contingents ahead of us, and came barreling down the street toward us. Tear gassing sucks. You can’t see, breathe or function. My first instinct was to kneel and wait for it to pass over my head, which isn’t how it works. Paramedics poured water in our eyes, and then an amazing thing happened. The youth that had disbanded in all directions, running from the gas, linked arms and were marching back to the float as a unit. Teary red eyes were matched with chants of joy. It was pretty empowering.”

Tear gas or not, Petty is not slowing down for this year’s Pride celebration. “I am really looking forward to checking out the GLBT historical area. It’s going to be neat to visualize our history,” she says. “I can’t wait for Alicia Champion to be on the Main Stage. She worked her way up from the Xone Stage and was on VH1 this year; plus she has been a great friend and associate in playing my many events. I am also eager to hear Nadine Smith speak at the Spirit of Stonewall Rally. She does amazing work and is always a great speaker. I really hope the youth make it to the rally, because it is a great kickoff to the weekend and is usually poorly attended by youth.”

The most important day of your life

When Murray-Ramirez discusses new GLBTs marching in their first Pride, he is unable to contain his enthusiasm. “This year, we will have people stepping out for the first time, marching proudly that they are members of the GLBT community,” he says. “I will look upon them in the same way [as the first marchers] because they are heroes, bringing our community to our proper place in history.”

“We are the civil rights movement of the 21st century,” he adds.

Murray-Ramirez’s message of empowerment is mirrored in this year’s Pride theme – “Strength in Numbers.” And he is not the only prominent member of our community who claims to derive inspiration from Pride.

“I’ve marched in all the San Diego Pride parades,” says Wilson. “I will be in this one too. Why would I not? [They’re] fabulous! This is my weekend to have a good time and soak up all the atmosphere – a city of gay people on the streets, six-figure crowds. … It speaks not only to San Diego, but to the growth of our community as a whole.”

“People today still come out on Pride weekend,” says Dilno. “Whether that means making the decision to tell family or co-workers, or just being on the sidewalk and saying, ‘It’s OK to be gay’”.

But what is the final message that our community’s founding activists would like to stress to anyone attending Pride this year, for the 30th time or for the first time? If anything, it is a message of caution that we not get complacent based on how far the GLBT movement has come in recent years. Just as they did 30 years ago, many activists still wish to inspire members of our community to come out of the closet, demand equality and, perhaps most importantly, to vote in the upcoming presidential election.

“What’s the next step?” questions Murray-Ramirez. “Being involved in the political process! If you are gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender, the most important day of your life is not your birthday – it is Election Day. Because we are not full citizens with equal rights, and until the day that we are finally equal, we are going to continue to fight.”

“Marches are important. Parades are important. Every LGBT person should experience the parade and the festival, and we must never forget that, out of that experience, comes activists,” he says. “Maybe the media focuses on the flamboyance – but that’s the humor and the color of our community! People understand that our community has a great sense of humor, and that’s what’s kept us alive – our sense of humor, and our sense of style!”

|

|

Copyright © 2003-2025 Uptown Publications