-

- Lockyer: State constitution permits laws against same-sex marriage

- Pennsylvania Senate slur prompts apology

- Gay groups want DeMint apology for antigay comments during debate

- Baton Rouge court throws out same-sex marriage ban

- Census data shows many black same-sex couples are raising children

- Bay Area groups seek tolerance for transgender youth

- National News Briefs

- World News Briefs

feature

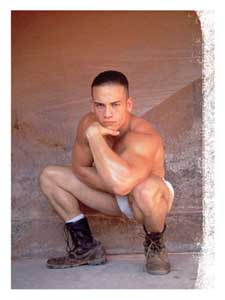

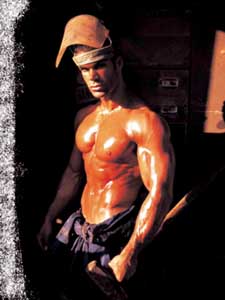

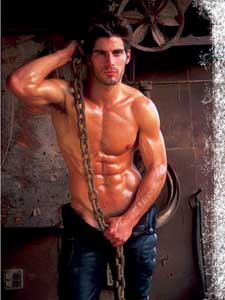

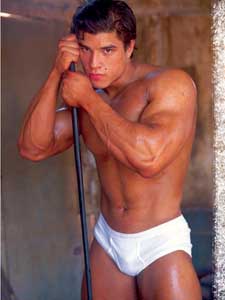

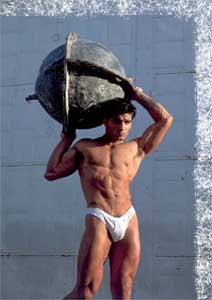

Raw, unrefined and rough

Lorenzo Gomez’s IRONMEN

Published Thursday, 14-Oct-2004 in issue 877

IRONMEN – the word incites and excites; it’s a raw unit, unrefined, rough and strong. It alludes to the rugged sweat-stained factory worker as he cranks a nut into place with the force of his bulging triceps. No frills, no quaffs abound, just man and machine.

An everyman’s fantasy of wandering into a factory as the day ends, stepping into the fading sun and shadow, seeing through the dust in the corner of the room a sweat-covered, work-chiseled hunk of man. He nods at you, grunts a command for a tool out of the chest. You grab the tool — the glint of steel in sunlight blinds you for a second as you look up and hand it to him. He works the last piece into place, groaning from the force, and turns around with a look of satisfaction. ‘Thanks bro,’ he says, wiping the sweat and grease from his forehead with the bottom of his white T-shirt, revealing a trail over abs down to his belt buckle.” Should I continue?

You turn to the next page of IRONMEN, by Lorenzo Gomez, and your mind trips off to the next fantasy. It’s a coffee-table size book of Gomez’s latest photography, filled with a hundred pages of masculine, real men just within your reach. After the success of his last book, Dios Latino, with only Latino men, Gomez expanded the scope of IRONMEN to include men of other races. He believes it was the right choice.

Gomez, a second-generation Mexican-American photographer from Los Angeles, started his quest in photography at the age of 10. At the time, his family ordained him with the responsibility and privilege of “the operator of the family camera.” He took this role to heart, and soon became the expert on everything involved with family photo-ops. Now 51, Gomez reflects upon his experience as what sparked his interest in the art of photography. He also shares the story of being a second-generation Latino in the rapidly changing city of Los Angeles.

“I am a mix of Mexican, Irish and Chumash, a Native American tribe located from Malibu through Santa Barbara. My dad’s family was born and raised on Catalina Island, and he considered himself to be a full-blooded Mexican. He’s never admitted to being an American, because he was very Mexican-nationalistic. [The United States occupied Catalina Island and took it from Mexico during westward expansion, as it did with most of Southern California.] His mother was part Mexican, and she was a quarter Native American,” Gomez said.

“Growing up, I’ve always been the minority within the minority,” he continued. “When I lived in Compton, it was a predominantly black city. The Latinos in Compton were a minority. When I was 12, we moved to a city called Pico Rivera, so I became a minority in a predominantly white community. During my youth in Los Angeles, the people of true Latino origin [usually immigrants and first generation] had no concept of why I didn’t speak Spanish or share the same culture. When I have gone into a service-related store, there has been an expectation that I can communicate in Spanish, so there have been awkward moments at times. The Spanish-speakers look at you like you are looking down on them, or something. You look Latino, but sometimes it appears that they think you’re too good for them, as if you used to speak Spanish but don’t do it anymore, which isn’t the case with me. I just never had the need to learn Spanish.

“I’ve encountered this kind of situation a lot over the years, but more so recently. For my profession, I haven’t needed it. But it would probably be nice if I did learn it. Most of the people I know and work with speak English as their main language, even though I live in a more Hispanic area at this time, having settled in the Whittier neighborhood. Now that I am 51, the demographics have changed to be much more Latino in Los Angeles. I don’t feel so much like a minority anymore as a result of all of the Mexican and Latina American immigration. Both of my parents were bilingual as I was growing up. The culture just wasn’t passed down to me, because of the stresses to assimilate to the dominant American culture. It was necessary to be as American as possible, because of what my parents considered the repercussions of being ‘too ethnic,’ having an accent, or maybe some racial bias against me or my family. I grew up without the Spanish language, or culture. It was a similar situation for my partner as well.”

Being gay has also played a part in Gomez’s life and in his photography. “My sexuality is an inseparable thing, a part of me. I shoot models I’m attracted to as a gay man. I’m visually oriented toward what I would call beautiful men. I don’t want them to be overly beautiful, but as good as possible in an image. I think a lot of it is sexual, if the models aren’t nude, [but if] they are close to it. I’m attracted to masculine-looking guys. I have rarely photographed women, yet I’ve done it with clients for business projects. If it is someone who comes to me and wants a portrait or headshot, portfolios, I’ve photographed every kind of person. But day-to-day, to be exciting, fun and creative, I photograph men,” said Gomez. “In the beginning, most of the models were straight, because I found them at the gym I went to. The book has both gay and straight models. I want people to look at an image and not think they are gay or straight, but just that they look great. Nobody wants to know the truth though, and I won’t tell them because I don’t want to bust their fantasy. I rarely shoot people who model for a living. My subjects are black, Latino and white in this book.”

Gomez discovered a property of lighting in his latest book that has inspired his future book. “I’m drawn toward a golden light,” Gomez said. “My next work has a lot of it, and I love the late, lazy afternoon kind of light, soft, and made the models a certain kind of feeling with the light and composition they’re in. The current book has an underlying theme that is industrial, and the models are shot in this setting. The background is a factory, with natural lighting. I believe it is more masculine than homoerotic, but it has been termed that way. The overall way the images are shot with the people is done in a very masculine way: The models are rugged guys, the background is hard, strong and rigid, and what they wear reinforces work attire.”

Unlike many modern photographers, Gomez still shoots with real film. Gomez says, “I’ve always shot with film. I look for the composition and lighting to work together. I have a great model to photograph right off the bat. The dilemma is where to shoot them, to get the image that matches the model, or creates something that makes the model look even better. I’m always trying to find the right background; my forte is shooting outdoors.”

Gomez will be at Bourbon Street promoting his book IRONMAN, Saturday, Oct. 16, at 8:00 p.m. He’ll be there to sign and sell copies. Several models from his book will be there dancing and signing pictures.

|

|

Copyright © 2003-2025 Uptown Publications