-

- Veteran radio talk show host David Brudnoy dies at 64

- Some stations air diversity ad that major networks rejected

- Student suing over gay T-shirt ban drops out of school

- Police shut down bar where play with nude performers was shown

- Traditionalists win the latest round, but United Methodist Church dispute far from over

- Judge awards visitation to former same-sex partner of Utah woman

- New York judge rules same-sex couples have no right to wed

- National News Briefs

- World News Briefs

Arts & Entertainment

Oscar Wilde’s

clubkid progeny

Published Thursday, 16-Dec-2004 in issue 886

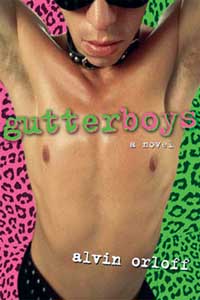

Alvin Orloff’s latest novel is yet another of his wonderfully whimsical yet astutely political gay tales. Set in the early ‘80s, Gutterboys (Manic D. Press) is the coming-of-age story of Jeremy, a postmodern gay new wave clubkid anti-hero with blue hair, tight punky jeans, a neon lime-green skintight T-shirt (along with zillions of other outfits and hair colors, of course), and a fierce crush on the brilliant, gorgeous, intellectually rigorous, mill-town-born Colin, who never returns the love – or all the loans – but proves to be something of a Virgil to Jeremy’s Dante, showing Jeremy the way around New York gay scene. In the process, he paints a sweet and nostalgic – albeit wisely cynical – picture of underground queerness on the cusp of the AIDS epidemic, a presence that haunts the novel at every turn.

On top of the looming specter of the plague, Jeremy is also haunted – and hounded – by his two grandmothers, one a proper English matron, the other a socialist Russian Jewish immigrant. They constantly second-guess his decisions in love and fashion, but always in that loving, indulgent, grandmotherly way. In both cases, their advice is usually spot-on, given the dubious quality of Jeremy’s judgment. Gramma Bea, the English matron, usually seeks to protect his pride (“Hold your head up high!”) when he finds himself in a doomed and humiliating love affair, while Nana Leah offers such instructive nuggets as: “Socialism means the collective ownership of the means of production, not studded leather wristbands.” Orloff prevents the women from becoming heavy-handed or pedantic in their advice by injecting it with a humorous tone, often laced with a sarcasm that’s reminiscent of Oscar Wilde.

The two grannies are an interesting and sincere depiction of Jeremy’s inner familial voice, a topic rarely explored in gay fiction in such a heartfelt way. Ultimately, though, the old women serve a larger purpose, embodying Orloff’s sense of history and American culture’s penchant for ignoring or forgetting it. It’s a problem he discusses with erudition in the book’s prologue, an excellent essay that could stand alone as a treatise on fin-de-siècle (the 20th century, that is) America. Take Jeremy’s advice and listen to your grandma!

Of course, Jeremy is also listening to Colin, whose simple motto is “have fun” regardless of how depressed you are or how bad things get. And they do get bad for Jeremy, including problems with money (jobs in a bathhouse and as a bike messenger offer insight and hilarity), venereal disease, eviction, a comic mugging, the ongoing unrequited love and all the boys who take his coveted place with Colin, and the misadventures of his tragic-comic stab at hustling – poor Jeremy doesn’t have much business sense. Through it all, Orloff’s story captures the brilliance of punk and new wave culture – the do-it-yourself ethic of self-reliance – in those heady days in San Francisco and New York, when being a brilliant “freak” placed you at the apex of gay culture, at least in some circles.

Orloff knows his stuff, having been at the center of queer punk in the early ‘80s. DJ’ing at Baby Judy’s and for Klubstitute, a seminal club and cabaret in San Francisco; co-authoring Bambi Lake’s fabulous tell-all biography, The Unsinkable Bambi Lake; and appearing in Manic D Press’s anthology Beyond Definition in the early ‘90s with his uniquely humorous and deeply political voice. His first novel, I Married an Earthling, tells the story of an alien hairdresser’s love for a gay Goth nonconformist teenager, and has to be one of the most unusual gay love stories ever penned.

Like Jeremy’s love interest Colin, Gutterboys is strangely and defiantly cheerful without being trite or sentimental. Orloff has worked his magic to turn a politically aware, socially conscious, flat broke gay boy into someone who’s fun to watch and root for. He reminds us that you don’t have to be in denial to be happy, an assumption that’s so ‘90s, so 21st century; you just have to have an open heart – and perhaps a drug connection, some cranberry red hair dye and a nice outfit. Or, in the immortal words of Oscar Wilde, who’s quoted by Orloff in the preface: “We are all of us in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.”

Trebor Healey is the author of the 2004 Ferro-Grumley award-winning novel, Through It Came Bright Colors.

|

|

Copyright © 2003-2025 Uptown Publications