Arts & Entertainment

The power of ‘Sorrows’

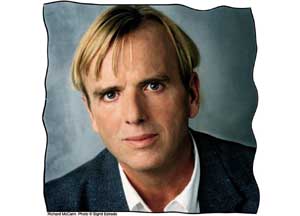

An interview with writer Richard McCann

Published Thursday, 28-Apr-2005 in issue 905

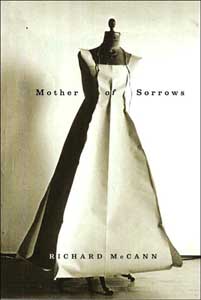

Mother of Sorrows (Pantheon Books, 2005) by Richard McCann is a book that I, and many other readers of gay prose, have been anticipating for almost 20 years. Since first reading the short story “My Mother’s Clothes: The School of Beauty and Shame,” in the 1988 anthology Men On Men 2, I have been waiting for the opportunity to further explore McCann’s exquisite prose in book form. Over the years, I have gotten to know McCann, and to become familiar with his poetry, including the Beatrice Hawley Award and Capricorn Poetry Award-winning Ghost Letters. But now, all of our patience has been rewarded with Mother of Sorrows, in which McCann’s reliable and unfaltering narrator takes us through his suburban 1950s childhood to urban adulthood, from the medina of Morocco to the Eagle Lake Lodge and Cottages of the Adirondacks, all the while acquainting the reader with one of the most unforgettable and complex families in contemporary American literature. McCann has spent 17 years as co-director of the graduate program in creative writing at American University in Washington, D.C. and regularly teaches at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown during the summer. I recently had the pleasure of speaking with McCann about his new book.

Gay & Lesbian Times: As someone who is a poet, a novelist and an essayist – if you had to rank your preference for each genre, how would you do it?

Richard McCann: I don’t think of myself in those terms. I did think of myself for many years a poet and I wrote and published, as you know, only poetry for a long time. I actually think of myself now as someone who is working from autobiographical sources and I think of myself pretty solidly in those terms. From that point, what something becomes is a different matter. I actually tend to regard the work as all being of a piece and that it’s linked, really for me, very deeply by autobiographical explorations. Sometimes those explorations either require or inadvertently take on fictional aspects and that’s why, in my mind, they’re fiction, for no reason other than that. In essays I really often try to think about, “What’s the story here?” … If I were to rank myself right now, I think of myself, although it’s open to change, as a prose writer. I don’t really make the distinction between fiction and non-fiction that much.

GLT: The constant throughout the book is the voice of the narrator. I think that’s what connects it as a novel.

RM: For me that does, too. That and if one were to think of it as a novel, although I don’t know if this makes it a novel, it seems to me that all the stories are about loss. They move from a frightening premonition of loss from the mother saying, “One day I will be dead,” to the narrator in the last story being a survivor of a lot of people; being a very tentative survivor because he himself is ill. To me, the base also seems very linked by questions of loss and what it might mean to be at least a provisional survivor.

GLT: The brother relationship is unlike any I have ever come across. Early in the novel, the narrator admits to scrawling, “I HATE DAVIS,” in reference to his brother, on a notepad near the telephone in his parents’ house. And yet Davis is full of surprises, including that he is, like the narrator, also gay. That took the relationship to a whole other level.

RM: Yes, I hoped so. I hoped that [the fact that] he becomes gay isn’t too great a surprise, I never know if it’s too great or not, but it’s a surprise to the narrator. I guess to me, Davis seems sort of depressed in a certain way after the father’s death through a lot of the book. He sort of recedes a bit and when he comes back out later in the book, he seems to be a very changed person, somebody we haven’t been looking at for a while, but has been depressed for a good, long time.

GLT: I’m glad that you mentioned the father, because there is also the theme of the father and the young son who knows he might be gay. For instance, the scene on page 22, after seeing cards his father had filled out describing him, the narrator asks, “Whose son did these cards describe?” and on page 80, the narrator says, “I had hoped to turn myself into a son he might love.”

RM: I don’t think of the boy, I should start by saying, as the gay son, because gay isn’t the way he is thinking of himself yet. He is just feeling different. I think of him as the sissy-boy son. I guess something that has really interested me, having been at least in my own mind a sissy-boy, was what that felt like. What it felt like to realize that you were not pleasing a person and what it feels like as a small child to understand that the love that is being described as unconditional is not feeling that way to you, because you’re already starting to fail [laughs]. There are images that you are supposed to be living up to. What’s being loved? Are the images that you’re supposed to live up to what’s being loved, are they what’s being desired, or is it the more frail actuality of what it feels like to be you? I guess for the boy in the book, he’s always worried that the frail actuality of what feels to him like him is not a loveable thing. There’s that wonderful anthology of gay men writing about their fathers that Bruce Shenitz put out. I really loved that anthology because it does strike me as a very complex thought. In the anthology it’s rendered so variously; men who were close to their fathers, men who were not close to their fathers, but nonetheless here is a figure of a man who more often than not is a straight man who is represented as the person you are supposed to be. I was named after my father and I look like my father, so that’s an extra thing. I felt that, in a way, I could not tell him, or could not allow to be seen that I wasn’t like him. I was very sorry that was the case, but I didn’t of course, have any language for that [laughs] and nor did he, he had no language either. There’s a point in the book where the narrator wants to go into a near creek, but he is afraid that he will slip and fall, and he thinks, “Why doesn’t the father cross back over to him?” Why is it only perceived as “I have to get to him,” and he doesn’t have an answer. I wonder what it’s like to be the father of the sissy-boy kid, probably to love that kid and to feel like, “I don’t know how to get over to where he is.” And the expectations of being able to relate in a certain kind of way. I don’t have a son or a kid, though I often wish that I did. I do think sometimes that if I had a son, one of the hardest parts for me would be allowing him not to be me [laughs].

GLT: Another unexpected character in the book is suburbia. It’s something that is being written about more and more. How do you feel, as being the sissy-son, what suburbia does to the sissy-sons?

RM: How I feel about suburbia is that I’m not sure it exists anymore; I don’t know that it’s that way anymore. I think for that boy, and for sissy-sons in general, it was incredibly isolating. The images that we were aspiring to were images of a certain kind of boy on a Schwinn bike with his other boy pals. I was a boy riding around on a Schwinn bike, but I also wanted to festoon my bike with streamers, that was the problem. Certainly the kind of suburb where I grew up, where everyone kind of moved in at the same time, there were no trees – none, not one – when we first moved in 1951, when I was just an infant. We all had these giant picture windows and there was a strong sense that you were being watched at all times, there was not a secret to be had. You were starkly visible in the stark landscape. I think what it must have been, not just for sissy-boys, but what it is to carry secrets around in that landscape was very difficult. The boys and the images that you’re learning don’t have secrets. One of the things that makes them boys is that fact that they don’t need secrets; they have a naturalness and ease in the world. I didn’t and the sissy-boy doesn’t; you don’t have the naturalness, because you’re stricken by a kind of self-consciousness of what you’re hiding. I went back to that suburb, it must have been 10 years ago now; my mother was still alive. I don’t live far from there now, but my mother had this desire to go knock on the door to the house where we used to live, she was very good at that, and, “Let me in. This is what I want to do, let’s do it.” We went and knocked on the door and I was very embarrassed. It was like, “Ma, ma, don’t knock on the door,” and she’s out of the car and up the sidewalk and she knocks on the door. The door is opened and there’s this big, hunky guy standing there and behind him, in what had once been our dining nook, I can see another guy who looks to be doing something like bagging marijuana. My mother says, “Hi, I bet you’d like to know what this house cost brand-new in 1950,” and the guy is like, “Yeah!” My mother and I went in and they were clearly a gay couple, they had their joint couple pictures in what had once been my bedroom and it was so weird, because I was so stunned and I didn’t like the way they had done up the house. It was a very small working-class house and they had frou-froued the whole thing, but my mother did; she thought it was great. So, there’s the two of us years later and my mother is walking around saying, “Ooh, a decorative light switch, I always wanted a decorative light switch,” and they’re going, “We love you, lady.” They’re looking at me like, “What a sourpuss.” I think; “Good God, I’ve come back years later and it’s now like a gay neighborhood; there’s, like, gay people living there and I still don’t fit in. My mother is still doing better.”

|

|

Copyright © 2003-2025 Uptown Publications