-

- Radical right files language for Calif. same-sex marriage ban

- Michigan students suspended for rest of school year over ‘Love’ graffiti

- Senate sends same-sex marriage ban to Texas voters

- Michigan students suspended for rest of school year over ‘Love’ graffiti

- U.S. Attorney from Seattle to investigate embattled Spokane mayor

- American Psychiatric Association calls for same-sex marriage recognition

- Mass. Democrats formally endorse same-sex marriage

- National News Briefs

- World News Briefs

feature

Loss, grief and ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’

Published Thursday, 26-May-2005 in issue 909

“[H]omosexuals have privately served well in the past and are continuing to serve well today.”

-General Colin Powell, during a Senate hearing on the subject in 1993.

For nearly six months, Specialist Friday existed in a world seemingly departed from common sense and reason; he kicked in doors and arrested perfect strangers, listened to the sounds of mindless calamity and the inevitable screams that followed. At the end of a workday filled with decidedly uncinematic levels of violence, he and his men could return to their tent to watch the latest Sopranos DVD or play a game of Counter Strike, venting the frustrations of real-world warfare out on a competing friend playing the part of the digital terrorist. While the past few weeks have provided a lull in the violence, not a day goes by without a random sniper attack or roadside detonation. It’s a sensation he knows very well: Not long ago one of the devices killed his boyfriend.

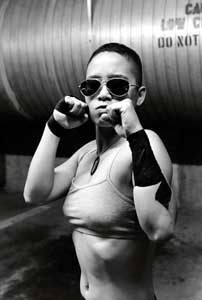

Friday’s sitting in a torn, overstuffed leather chair in the corner, a cold and untouched cup of coffee in his calloused hand. His voice is even and confident, his gaze unblinking. The sunlight reflecting through the window next to us is hard and bright enough to cause me to squint, but the specialist seems immune. There’s a lean, toned minimalism to the 20 year old; from his cheap black T-shirt and brandless jeans to the cropped haircut. Even from a distance, it’s obvious he’s a soldier. His demeanor is notable, especially if you know what to look for: that unforced maturity, the way he swaggers instead of walks – a product of habit rather then any misplaced sense of pride.

Friday’s parents never knew he was bisexual, nor did many of his friends or teachers.

“While there may still be a military funeral held in the service member’s honor, the surviving partner will not receive any words of support or sympathy from the military, and that folded flag, so synonymous with tragedy, will instead be presented to the surviving next of kin.” Growing up in the Bible belt, it’s an exercise in Darwinism to learn to hide that sort of behavior, lest somebody smear you into a wall or beat you in the street. Nobody suspected, not even the Army recruiter who promised him all the things a recruiter can legally get away with to lure a lonely and poor young man: patriotic fellowship, money for college, free health care and a chance to see the world. “Sure, I knew what I was getting into when I signed up… but, you know, what the hell… it wasn’t like I had anything better to do,” Friday says. “I didn’t have any money for school, and my recruiter knew it.” A year after basic training, endless deployment exercises and rumors of war, his unit left for Iraq.

“Everyone,” Friday explains, “just called it The Sandbox.”

“They’d put the IED’s [improvised explosive devices] in anything, you know?” he continued. “Dead animals were a favorite – one minute we’re looking at road kill, the next minute we’re taking cover or looking into a crater. I’ve never seen it, but I’ve heard that the best way to tell road junk from an IED is to look for an antennae. They use cell phones as detonators, and just call it in when a convoy passes.”

Friday thinks frequently of the event, rolling over it again and again; the images mark his every waking moment, ingrained by too little time and too much thought. Most of it, he says, is just a blur of vaguely connected pictures and sound, like a badly scratched DVD. The convoy passes, the only noise coming from the engines and tires against un-maintained road. Sand gets everywhere. The heat and desert is a harsh enough environment that support personnel and mechanics are constantly working to keep the trucks and Humvees running. Sometimes the lead driver will notice something out of place – a twisted and cracked chunk of concrete in the middle of the road or an area of broken gravel where something might have been buried – and halt the convoy. More often then not, these telltale signs of danger are ignored or overlooked. A waiting insurgent will watch the road, waiting for just the right moment before igniting the block of explosives.

“I was about a hundred yards from the lead Humvee when it went off,” Friday says. “I wasn’t even looking at it.”

His voice remains perpetually monotone, reciting a story he keeps living through but has only shared with a select few. “We all felt it before we saw it… just this god-awful bang. It’s not like the movies. No fire or flames or anything, just a big boom and lots of smoke and falling rocks. Everyone’s screaming something, the LT’s ordering everyone around but nobody’s really paying any attention to him…. Nobody really heard him. Not at first, anyways. It was just complete chaos; the lead vehicle’s a complete mess…. I didn’t find out about [my boyfriend] for another five minutes.”

Our conversation is conducted in the questionable privacy of a local café, a hole-in-the-wall kind of establishment with tobacco-stained walls littered with bad paintings. It’s early enough in the day that there are few customers, and he seems relatively at ease describing the circumstances of his story.

In order to be interviewed for the article, there were ground rules: Because he is still in the military, I would not publish his real name, his home unit or the name of his partner. While the number of GLBT service members expelled has fallen significantly in the past year, it is still common enough to cause the specialist a justifiable sense of dread. His sense of paranoia is well founded, considering the complicated history between gays and lesbians and the military.

Sadly, the theme of Specialist Friday’s story is not unique. As of this writing, 1,623 soldiers, sailors, marines and air personnel have died during Operation Iraq Freedom, and an additional 182 have died in Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan. An estimated 15,000 have been wounded in Iraq alone, while an official tally of wounded vets from Afghanistan remains unavailable. While “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” claims that gays, lesbians and bisexuals can still serve, hundreds are expunged from the service every year. Under the current political climate of legal discrimination, it’s unsurprising that no official military tally has been made of GLBT members who have died in the line of duty.

While it is impossible to truly know how many gays and lesbians now serve, the Center for the Study of Sexual Minorities in the Military (CSSM) suggest a conservative number of 60,000, and those members face an uphill battle when it comes to wearing the uniform. From the time they take the oath of enlistment to the day they leave the service, they live in a world of endless scrutiny; where the slightest slip of the tongue could lead to a dorm-room beating in the middle of the night, or, if they’re lucky, an administrative or dishonorable discharge.

“In turns he is both bitter and welcoming when it comes to the media. Bitter, because he knows what kind of trouble this could lead to should his name become public, and welcoming because he wants his partner’s story to be known.” The 1999 murder of Private First Class Barry Winchell is still fresh in the minds of gay service members – to many it’s a reminder that many still fear and revile the very idea of serving with homosexuals. Pfc. Justin Fisher, a young and impressionable man at the time, was encouraged by other soldiers in his unit as he beat Winchell to death with a baseball bat while he slept.

After Friday and his partner started dating, he couldn’t help but think of Winchell. “For the first couple of weeks, I kept looking over my shoulder, waiting for somebody to find out,” he says. “After a while, I just broke down… I mean, you can’t worry all the time and stay sane. I just figured nobody cared.” It was only later that Friday would learn how painfully true that train of thought was.

In retrospect, Friday didn’t think he had it so bad. “I still dated women, so it wasn’t such a big thing. I never had any big dramatic scene when I realized I was bisexual… it was just like ‘well I guess I like guys, too.’ Until I met [my partner] I never really had any problems.”

He doesn’t like talking about those personal, private moments. When I ask, his lips briefly tighten together, buying himself a moment to think by taking a sip of his long ignored coffee. Finally, he responds, waving his hand dismissively. “I’m not going to talk about that. Just keep asking your questions.”

There is no uniform experience for GLBT service members, no set of memories shared amongst them. In a recent survey conducted by the CSSM, members expressed their varied opinions of the military: Some served openly within their unit, while others kept their sexuality so deeply hidden that they created fake girlfriends, families and histories in the hopes of cementing their perceived heterosexuality. Friday was lucky enough to go the middle route. “Some people knew… I mean, it’d be hard for them not to. I never just directly came out and said ‘hey, look at us, we’re a couple.’ But looking back, it’d take a pretty dense person not to figure things out.”

Thankfully, Friday’s LT was just that dense. “He was a terrible leader, did a lot of grandstanding, lots of speeches and stuff… nothing he ever said really connected with the rest of the men. I think it’s just because of his background… no prior enlisted experience, upper crust, ROTC all the way…. That sort of thing makes it hard for an officer to really reach the men and women beneath him. It’s even harder for those people to respect him.”

An E-4 specialist, on the other hand, is a strange sort of pay grade that straddles the line between the lower enlisted personnel and a non-commissioned officer (NCO). Some specialists, such as Friday, are treated like NCOs with all the responsibility and expectations of a man with higher rank, such as training other junior enlisted personnel and maintaining squad morale.

“I knew all the arguments against letting gays serve,” Friday continues, “that it’d be ‘detrimental to unit integrity’ and that soldiers wouldn’t want to stay in a foxhole with somebody if they’re worried they’re always going to be ‘checked out.’ I’m complete proof that’s just complete bullshit.”

While the United States has little empirical data to back up either side of the debate, every member country of the European Union (including our allies, the British) are legally required to allow gays and lesbians to serve. They’ve quietly done this for the past several years, and all the arguments used against letting gays serve have been thrown out the window.

Friday doesn’t like talking about politics; suffice to say that both he and his parents are lifelong Republicans. When pressed, he’ll only go so far as to say the war “was a fucking nightmare of an idea.” By now he’s still nursing his first cup of coffee, while I’m deep into my third or fourth, trying to keep the line of questions going.

“For straight couples, the military provides everything for you when somebody close to you dies. Where the hell am I supposed to go? We can’t even go to each other for support.”

In turns he is both bitter and welcoming when it comes to the media. Bitter, because he knows what kind of trouble this could lead to should his name become public, and welcoming because he wants his partner’s story to be known.

“When [my boyfriend] died, he had a military life insurance policy, but because he named the beneficiaries ‘by law’ instead of using specific names, the cash all went to his parents. He hasn’t spoken with them in years,” Friday says.

The life insurance policy, known as Service Group Life Insurance (SGLI), can leave up to $250,000 to anyone the service member names, but because of lingering fears of being “outed” Friday’s boyfriend left who would be given the money up to military lawyers. “It just chaps my ass that these parents who didn’t want anything to do with him when he was alive are rolling in his cash now that he’s dead,” Friday says. “It’s awful; I had friends at his wake who said his parents were just eating up all that sympathy people gave them.”

Money isn’t the only thing denied to same-sex military partners. While a heterosexual family, left behind by the death of their loved one, can expect a visit by a casualty assistance team (often an officer and chaplain attired in their formal-dress blue uniform), same-sex couples must learn of their loss through second-hand means. Often, the news of their partner’s death comes to them days or even weeks after the actual event. Heterosexual survivors can also count on free or near-free college tuition for their children, on base housing until they can get back on their feet, free health care, grief counseling and a myriad number of family support programs. If a member died in combat, his or her family will be invited to a full military burial, a sad time and place complete with the 21-gun salute, intonation by a chaplain from the same service and the neatly folded flag presented to the widow or widower.

What can a same-sex partner expect? Before and during World War II, the American military forces had a somewhat more enlightened approach to the subject than we have today. Because of the massive need for support, combat and intelligence personnel, many same-sex liaisons were often overlooked. During the war itself, few service members were actually drummed out for their activities. Indeed, an official Army psychiatrist report stated that a large percentage of homosexuals possessed sufficient restraint and insight and had sufficient talents to justify careful examination of each individual case believed to be homosexual before taking any action against such individuals. Following the war, and the ensuing age of McCarthyism that followed, this report was ignored.

Today, aside from the sympathy of perhaps a few friends, the surviving partner shouldn’t expect anything. An active service member or drilling reservist cannot list their partner under any of the aforementioned support programs. While there may still be a military funeral held in the service member’s honor, the surviving partner will not receive any words of support or sympathy from the military, and that folded flag, so synonymous with tragedy, will instead be presented to the surviving next of kin. In Friday’s case, that flag was presented to parents who had long ago stopped speaking to their son.

The cynically-named military code “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” states that homosexuals can serve in the military, so long as they do not openly disclose their sexual identity, or take any action that a reasonable person could find to be of a homosexual nature. Such actions or admissions are grounds for an immediate investigation, and usually an administrative or other-than-honorable discharge. Listing your partner for casualty support is just such an action. The public affairs officer at USMC Miramar was unavailable for comment at the time of this printing.

Friday looks down at his coffee for another moment, as if contemplating whether or not to finish it before speaking. He seems physically tired from the interview; his shoulders slumped and his gaze oddly introspective. “I know there’s other people like me, guys who’ve lost boyfriends or women who lost their girlfriends. For straight couples, the military provides everything for you when somebody close to you dies. Where the hell am I supposed to go? We can’t even go to each other for support…. I don’t mind the jokes, the stupid names, the way everyone uses the word ‘fag’ like we’re gimps or something. The worse part of it all is the feeling that you’re alone.”

The soldier, still weary and grieving, suddenly moves to his feet, abandoning the still full mug on the table, leaving me with one last word of advice: “You should tell people they’re not alone. You’d be surprised… just hearing that kind of thing helps.”

|

|

Copyright © 2003-2025 Uptown Publications