-

- Supreme Court confirmation hearings have grown tougher over the years

- Milwaukee Gay Arts Center fights city over nude review

- Anti-gay church protests at funerals, drawing counter-protesters

- Campaigns gear up in fight over Texas same-sex marriage ban

- Two Arkansas disc jockeys plead guilty in gay porn case

- National News Briefs

- World News Briefs

Arts & Entertainment

Of poets, scholars and unexpected visitors

Published Thursday, 01-Sep-2005 in issue 923

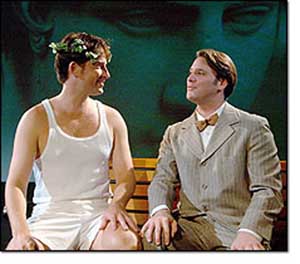

The Invention of Love

Sir Tom Stoppard (he was knighted in 1997) is drunk on words, a fact which makes his plays at once fascinating and challenging. You can’t slide through a Stoppard play like, say, a Neil Simon; you have to pay careful attention just to keep up.

Nowhere is this more evident than in The Invention of Love, a meditation on courage, scholarship, friendship and, of course, love, surrounded by a dense thicket of historical and literary references involving characters most Americans remember only vaguely, if at all. The first act features the croquet-playing John Ruskin (Manny Fernandes), Benjamin Jowett (David Gallagher), Walter Pater (Tom Stephenson); the second act sports a different quartet, this time journalists and an author, but all discuss topics that will leave the average theatergoer in the dark: textual criticism, Roman writers, Latin translation, the function of art.

The challenge of The Invention of Love, with all its historical and literary references, is to make a dramatic piece out of what is essentially a disquisition on literature and criticism, and to keep the audience from burying its nose in the study guide thoughtfully provided by Cygnet Theatre director Sean Murray.

The main protagonist in Invention of Love is poet and Latin translator A. E. Housman. The play jumps back and forth in time between Housman’s death and his time as a student at Oxford. As the play opens, Housman (Jim Chovick) is being ferried by Charon (Tim West) across the River Styx (on the theater’s newly installed turntable).

“So I’m dead, then,” he says. “Good.”

On the other side, his younger student self (Sean Cox) meets the (unrequited) love of his life, Oxford roommate Moses “Mo” Jackson (David Humphrey), who becomes at once his greatest joy and his greatest sorrow.

Jackson, the golden boy, track athlete and science student, captivates Housman and fellow literature student Alfred Pollard (Tristan Poje), who notes that Jackson “seems quite decent (despite his major).”

The first act alternates between typical Oxford high jinks (“three in a boat” rowing on the Thames, for example) and croquet games with scholarly discussions by the aforementioned experts.

In 1895, the flamboyantly gay Oscar Wilde (Daren Scott) is imprisoned, to die later in exile. Housman, meanwhile, has obtained a position at Cambridge, living out his life as a closeted academic.

Stoppard invents a meeting between the two in order to juxtapose them: Wilde, who lived as he pleased and paid a heavy price in calumny and public disapprobation; Housman, who lived a quiet, proper and closeted life but suffered the regrets of the timid. This is where the drama lies.

One can be forgiven the conclusion that Stoppard is showing off more than he is trying to write a good play here. Critic Robert Brustein puts it better than I could: “There is not enough plot here for 20 minutes of action, but there is enough erudition for a fortnight.”

Nonetheless, The Invention of Love is worth seeing for the fine performances (Chovick and Cox as Housman and Scott’s Oscar Wilde are particularly effective) and Murray’s inventive staging (Projections on the back wall and the new turntable are especially effective). Just remember to put on your mental track shoes.

The Invention of Love plays through Sept. 25 at Cygnet Theatre. Shows Thurs.-Sat. at 8:00 p.m.; Sun. at 2:00 and 7:00 p.m. For tickets, call (619) 337-1525 ext. 3, or visit www.gaylesbiantimes.com for a link to Cygnet’s Web site.

Bloody Poetry

In 1816, the most celebrated living British poet, Byron (Giancarlo Ruiz) and English revolutionary poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (Thomas Hall) met when they took adjacent summer houses in Switzerland. Byron took along his personal physician, Dr. Polidori (James Steinberg); Shelley and his wife-to-be Mary (Celeste Innocenti) and her stepsister Claire Clairemont (Sara Jane Nash), one in a growing list of Byron’s cast-off lovers. It would be the first meeting between the two poets.

All of them were upper-class revolutionaries on the run from Victorian convention. Nineteenth century hippies experimenting with free love: Byron, the charming and eccentric lion of English poetry; Shelley, the struggling revolutionary upstart.

Playwright Howard Brenton’s Bloody Poetry, directed by Doug Hoehn, gives us poets speaking cleverly but acting badly, discussing the function of art and the relative merits of other poets such as Wordsworth and Blake, while the promiscuous Byron unapologetically adds to his list of conquests, and Shelley abandons his wife and two children for bloody poetry and the life of a libertine.

That’s the first act: literary discussions and Mary’s attempts to save Claire from her own foolish actions, which unsurprisingly result in her pregnancy.

The second act, bleaker in tone and more episodic in structure, records “the rest of the story,” concentrating on the effects of Shelley’s desertion on his wife. She goes more than a little mad, takes to whoring and finally kills herself, leaving Shelley a lifetime of guilt and regret, not to mention frequent ghostly visits.

Claire, too, is left to deal with Byron’s child. His comment, when told of her pregnancy: “Damn! Why didn’t I stick to boys?”

Ruiz and Hall are excellent as the poets, and Nash and Steinberg are also fine as Claire and Polidori. But stealing this show is Innocenti’s Mary: calm, steady and wise, the anchor that keeps these flighty birds tethered to some semblance of reality.

Bloody Poetry plays through Sept. 14 at 6th@Penn Theatre. Shows Mon.-Wed. at 7:30 p.m.; Sat. matinee at 4:00 p.m. For tickets, call (619) 688-9210, or visit www.gaylesbiantimes.com for a link to the Penn’s Web site.

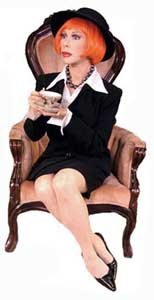

The Tale of the Allergist’s Wife

Playwright Charles Busch specializes in the outrageous. Probably best known as the author and transvestite star of Vampire Lesbians of Sodom and other classics, one has come to expect characters bigger – or a least flashier – than life.

With The Tale of the Allergist’s Wife, the only play not written as a vehicle for himself, Busch moves into safer, more mainstream territory: straight (well, mostly), uptight New York Jews.

Marjorie (Leigh Scarritt) lives in an upscale, tastefully decorated Manhattan loft with husband Ira (Fred Harlow), the allergist of the title, whose job supports a lifestyle many might envy.

Marjorie isn’t bigger than life, but she is louder – especially if you’re in the front row of a small theater. As the show opens, she hides under a blanket on the couch, suffering the torments of the undereducated. Though she can toss around names like Kafka, Kierkegaard, Rimbaud and Schopenhauer, she feels uninformed, confessing that she doesn’t understand Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, which apparently threatens to ruin her life.

Marjorie has another problem as well: her grouchy old mother Frieda (Carlyn Ames), a sourpuss who kvetches about everything, especially constipation, which becomes a running (and annoying) joke.

Into this depressed milieu drops Marjorie’s old school chum Lee Green (aka Lillian Greenblatt), who unlike Marjorie hasn’t spent her life kvetching. She’s been fund-raising for political organizations, and has acquired a name-dropping list a mile long.

Lee’s life-is-fun attitude fascinates but frightens the stuck-in-the-mud Taub household, especially when she starts playing up to Ira and gets touchy-feely with both of them.

This is a slight piece, and where it will go should be more of a question mark, given the playwright, but the predictability didn’t seem to bother the audience I was in.

Scarritt is excellent, though her voice needs to be toned down a bit for the small 6th@Penn space. Harlow, Ames and Rhys Green (as the building handyman) are all fine, but the show belongs to Bedington’s Lee, whose serpentine seductiveness takes over and makes us all wish we were a little more daring.

The Tale of the Allergist’s Wife plays through Sept. 25 at 6th@Penn Theatre. Shows Thurs.-Sat. at 8:00 p.m.; matinees Sun. and Wed. at 2:00 p.m. For tickets, call (619) 688-9210, or visit www.gaylesbiantimes.com for a link to the Penn’s Web site.

|

|

Copyright © 2003-2025 Uptown Publications