-

- Supreme Court confirmation hearings have grown tougher over the years

- Milwaukee Gay Arts Center fights city over nude review

- Anti-gay church protests at funerals, drawing counter-protesters

- Campaigns gear up in fight over Texas same-sex marriage ban

- Two Arkansas disc jockeys plead guilty in gay porn case

- National News Briefs

- World News Briefs

Arts & Entertainment

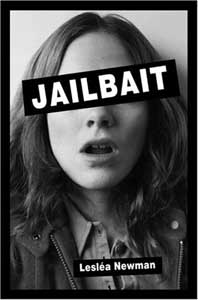

‘Jailbait’ tale

An interview with author Lesléa Newman

Published Thursday, 01-Sep-2005 in issue 923

In Jailbait (Delacorte Press, 2005), her new young adult novel, Heather Has Two Mommies creator Lesléa Newman takes the reader back in time and back to high school, where Andrea Robin Kaplan, a lonely sophomore, becomes the object of the affections of pedophile Frank. Frank’s inappropriate attentions are an unexpected reprieve for Andrea from her social outcast status at school and her role as dutiful daughter at home. Although she knows it’s wrong, it is through this painful and complicated experience that Andrea is able to emerge as a stronger and smarter person, and one who regains control of her life. I spoke with Newman about the ’70s, the suburbs and sexuality.

Gay & Lesbian Times: Your new young adult novel, Jailbait, is set in the early 1970s. Why did you choose 1971, and not, say, 1981 for the setting of the book?

Lesléa Newman: When I wrote the story, the first several drafts, I really didn’t have a time frame in mind; I just assumed it was contemporary. And then my very wise editor at Random House said to me, “This doesn’t read like a contemporary novel. It reads like the ’70s. So, you need to either bring it into the present or set it back in the past.” When she said that, I immediately got very excited about the idea of setting it back in the past, and I think that’s what was happening all along. It’s the time when I was a teenager, so I think it was easiest for me to get in the head of a teenager by putting her in the time period when I was her age. That’s kind of the reason, and then it became so much fun. Her brother Mike really epitomizes that time period; a really fun character to develop. I sent away for TV guides from that era, I looked up slang, I looked up the Top 40 hits during that time, and I really got into it.

GLT: Jailbait also examines parent/child relationships. Do you think they have changed much in 30-odd years?

LN: One would like to think so. I’m not a parent so I can’t really speak from direct experience, but from the teenagers I have met, when I go to talk at schools, etc., it seems like it really depends on the family. There are some kids who feel like their parents don’t have a clue as to what’s going on in their life, and that’s probably true, and there’s some parents who are very active and maybe even over-involved in their kids’ lives. I do know that teenagers have been and will always be very smart, and very capable of leading a double life if they choose to.

GLT: Additionally, Jailbait depicts the cruelty of teens toward one another, for instance, classmate Donald Caruso’s relentless teasing of Andrea, especially when he calls her a lesbian and a dyke in a derogatory fashion. Can you say something about the cruelty of teens, in both the pre- and post-Columbine culture, and why you chose to depict that in the book?

LN: I think Columbine is a perfect example. I think teenagers are incredibly cruel, and I think it all comes from their own insecurity. If somebody else is being picked on, then I won’t be the one getting picked on. I, in fact, was the second fattest kid in my high school and junior high, and I’m so ashamed to say that I participated in the teasing of the first fattest child because it wasn’t me. Of course any child who is perceived as different whether in fact he or she is or not, is a target. I mean there was a kid in my school who had four gray hairs. That kid was teased mercilessly for that, and of course any kid who was perceived to be gay or lesbian, that was just it. In fact, in 1999, I was invited back to my own high school, Jericho High School on Long Island, [where] I was inducted into their Hall of Fame. They did not tell the students that I was a gay writer, they just said I was a writer, and they didn’t tell them anything about what I had written, so I wound up coming out to 300 high school students during an assembly. Because it’s pretty impossible to talk about my work and not come out, not that I want to be closeted anyway. They were asking me all these questions and I asked them, “What’s it like for a gay or lesbian student here at Jericho High School in 1999?” There was this dead silence, and then one kid piped up from the back and said, “We don’t have any gay or lesbian students here,” which of course wasn’t true. A year later, I got an e-mail from a young woman who said that she was now in college, and she was at that assembly, and she knew she was a lesbian all through high school but wouldn’t dare come out because she knew how much she would have been tormented for that. She was so happy that I was at that assembly.

GLT: Another important message in the book is to never have sex without condoms. Was that your way to work in a necessary safe-sex message in this day and age?

LN: That scene really came out of the personality of Frank, who is Andi’s perpetrator. He’s a real creep on many levels, and he’s also got this side of him that in some perverse way really cares about Andi, and thinks of himself, in a way, as her mentor. So, he is imparting this wisdom to her that she should never have sex without a condom, and again, I wasn’t really thinking message, because that’s not the way I write. I was really just completely immersed in that scene, and I was actually very surprised that he did that, and pleased. Somebody once told me that nobody is 100 percent bad, and nobody is 100 percent good, and Frank really is about 99.9 percent evil.

GLT: The central piece in this is Frank and the pervasive theme of pedophilia. At the very end of the book, Andrea has this amazing line where she says, “Long Island is chock full of perverts,” which sort of sums up the suburban experience, especially in the ’70s. The flight of urban families to the suburbs to raise children, because they thought it would be safer for their children, when in fact it wasn’t necessarily safer.

LN: The book was really inspired by the Amy Fisher and Joey Buttafuoco situation. I became completely fascinated with that because I did grow up on Long Island during the second half of my childhood. I looked at that situation and especially the way she was portrayed. Just the phrase “Long Island Lolita” made my blood run cold. Nobody, not even the feminists, were portraying her as a victim. I really felt like she was a victim and that Joey Buttafuoco was the seducer. He really was the Long Island Lolita, in my opinion. Of course, Amy Fisher never should have shot Mary Jo Buttafuoco in the head, and I never would have condoned that in a million years. Before that happened, I just felt that when you take a teenaged girl, who doesn’t have a lot of self-esteem, who doesn’t have the greatest home life, who’s very vulnerable, who only wants to be loved, and you have an older man approach her who is sophisticated in some way or is perceived to be sophisticated and who says things to her like, “I love you, I don’t love my wife, I really want to be with you,” she’s going to buy that line. She’s going to do whatever he wants. And nobody seemed to be discussing that. I really wanted to write a story from the young girl’s point of view that really showed her psychological landscape. What I really tried to do in the book was show Andi’s perception of what was going on while at the same time showing the reader what was really going on.

I originally wrote it as a novel for adults. I wanted to show how damaging this kind of relationship could be to a young girl. The ending was very different, it was very dark. It went to about a dozen editors and more than half of them said it reads like a teen [young adult] novel. It was written in first person, the protagonist is 15 years old. I re-wrote it for a teen audience, which meant that I had to tone down the description of the sex that happens between the two characters. It’s not that it’s less frequent or less violent, it’s just described differently. When I say, at one point, in Andi’s voice, “Frank makes me do something so disgusting that I can’t even tell you what it is,” that was actually described, but it was changed to what I just said, and the reader gets to supply what they think it is the most disgusting thing that can’t be talked about. Whatever level the teenage reader is at, they will supply that. The other thing that was changed drastically was the ending. I feel like if I’m writing for teens, it’s really important for me to leave them with some kind of hopeful ending. It’s not a happy ending and it’s an open ending.

GLT: She reclaims her identity.

LN: Yes, she does. And I didn’t think it was fair to leave a teen reader devastated.

One thing I really wanted to say about suburban culture is that it’s a real car culture. You go from an urban environment where you’re on the subway, you’re on the bus, you’re on the street, you’re surrounded by people all the time, and suburbia is very isolated. You can get into a person’s car, and it’s just the two of you, and nobody knows where you are or what you’re doing.

GLT: Throughout the book, it’s the sound of his car she keeps hearing; the sound of his Volkswagen coming up. Even though we’re reading it, we can hear it, too.

LN: The way that image came to me was when I was in high school, my best friend and I walked to school every day rather than take the bus, and this light blue Volkswagen, who would give this little honk and wave, passed us everyday. We got all giggly and excited and kind of creeped out at the same time. He never got out of his car and we never spoke to him. But when I started to write this book, that image came back to my mind.

|

|

Copyright © 2003-2025 Uptown Publications