-

- In a capital where the disgraced try everything to hang on, Foley exits in a hurry

- Could Wisconsin end 20-state winning streak for same-sex marriage bans?

- Disputed AIDS bill passes House

- Judge rules same-sex R.I. couples can marry in Massachusetts

- Conn. gay rights group backs DeStefano over Rell

- Transgender inmate fakes own death

- National News Briefs

- World News Briefs

Arts & Entertainment

Of pigs, nuns and Bach wannabes

Published Thursday, 05-Oct-2006 in issue 980

Pig Farm

First it was pay toilets. Now it’s porcine waste, or “fecal sludge,” as the characters in Pig Farm often say.

Playwright Greg Kotis, writer of Urinetown, offers a co-world premiere (with Manhattan’s Roundabout Theatre) of his second play at the Old Globe’s Cassius Carter Centre Stage through Oct. 29, directed by Matt August.

Pig Farm is as odd a bird as its title suggests. It has elements of western films, farce, black comedy, slapstick and TV sitcom, all coming at you from a decaying farmhouse somewhere in the vicinity of the Potomac River.

Tom (Ted Koch) and Tina (Colleen Quinlan) are the farmers in question, trying to scrabble together a living from pork chops. Tom just wants to get past the imminent visit from EPA inspector Teddy (Ken Land), whose business it is to make sure nobody has too many pigs or (much more important) dumps fecal sludge into the river.

Tom, who has hired 17-year-old Tim (Ian White) on work furlough from juvenile hall, sends the kid out to do the count. The number is in the neighborhood of 15,000, but those federal limits make an accurate count mandatory.

Tom and Tina, who give the impression they may end up looking like Grant Wood’s “American Gothic” couple, speak in words of few syllables and tones of exhaustion. Tina, bored with washing, ironing and cooking, wants a baby; Tom says he wants to get them on a solid financial footing first.

Tim primarily wants to stay out of juvie, but he also has the hots for Tina, who annoyingly keeps calling him a “boy.” But it doesn’t take much to get her to “make a man out of him.” That scene, heavy with breathless overtones of The Postman Always Rings Twice, is one of the funniest, played with dialogue as overheated as the action.

Then there’s Teddy the suit, with dark glasses and attitude, who also finds Tina pretty cute.

Pig Farm was inspired by the aftermath of Hurricane Floyd in 1999, when the river flooded pig sheds, drowning thousands and overflowing the “fecal sludge” lagoons that then spilled into the river.

The play, nowhere near as serious as the event which inspired it, isn’t even as funny as it wants to be. Don’t get me wrong - there are many laughs, but the excesses of the script, at first amusing for its oddness, begin to wear, becoming downright annoying in the second act. Things like Tim’s exaggerated John Wayne/James Dean delivery, one of the best things about the first act, wears out its welcome. Likewise, the repeated use of certain lines for no apparent reason and the use of pork compresses to allay the wounds of the occasional violence, so funny the first time, get old. Ultimately, Pig Farm starts to sound too much like a sitcom, and the watch patrol begins.

Don’t blame the cast. They are uniformly splendid, as is Takeshi Kata’s set (especially that lovely rain effect).

Kotis has a skewed sense of theater, politics and life that I find appealing. But as Ellis Parker Butler said, “Pigs is pigs,” and there’s only so much one can say about pig farms and federal agents before the brain starts to glaze over.

Pig Farm plays through Oct. 29 at the Old Globe Theatre’s Cassius Carter Centre Stage. Shows Sunday, Tuesday and Wednesday at 7:00 p.m. and Thursday through Saturday at 8:00 p.m., with matinees Saturday and Sunday at 2:00 p.m. For tickets, call (619) 23-GLOBE or visit www.theoldglobe.org.

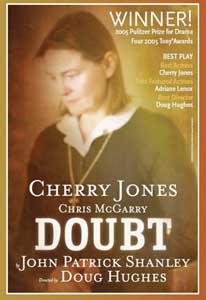

Doubt

“Doubt requires more courage than conviction does, and more energy; because conviction is a resting place and doubt is infinite.”

Playwright John Patrick Shanley

Sister Aloysius (Cherry Jones), principal of St. Nicholas Catholic school in the Bronx, is an old-school nun: heavy on authority and discipline and light on the fuzzy stuff. It’s 1964, and she runs her school with an iron fist - forget about that velvet glove.

Father Flynn (Chris McGarry) runs his brand of Catholicism differently. Doubling as a boys’ basketball coach, he favors a more accessible, Vatican II-style approach, inventing stories to illustrate his sermon points and not hesitating to reach out to the students.

It’s his reaching out that concerns Sister Aloysius, who at the beginning of school saw him touch a boy’s wrist. She thinks he’s a pedophile and seeks further corroboration.

Young Sister James (Lisa Joyce) provides it in the form of a suspicion. Donald Muller, a new eighth grader, returned to class from a private meeting in the rectory with Father Flynn acting strangely and with alcohol on his breath. Donald, the school’s first black student, is an altar boy.

This is all Sister Aloysius needs, and she sets out to force Father Flynn’s confession and/or transfer. She’s been around long enough to know that the testosterone-laden church hierarchy is not likely to expel him on her accusation, but she at least wants him away from her students.

Will she succeed? Should she? Can suspicion ever equal proof? When pedophilia is at issue, can one afford to wait for incontrovertible proof? Is suspicion enough to risk ruining someone’s career? How does job shuffling solve the problem?

Doubt, which took Broadway by storm in 2005, is on tour, with the two Tony winning actors and director Doug Hughes. It plays through Oct. 29 at the Ahmanson Theatre in Los Angeles. The production moves to San Diego on Oct. 31 for a one-week run at San Diego’s Civic Theatre.

The questions Shanley raises are important, though it seems to me that tossing in Donald’s homosexuality toward the end only dilutes the stunning, emotion-charged scene between Sister Aloysius and Mrs. Muller (Adriane Lenox), where the issues are authority and pedophilia.

Nonetheless, Doubt is a riveting exercise in ethics, especially relevant in this post-9/11 world. Boasting fine performances, the Broadway incarnation garnered eight Tony nominations and won four: best play, Hughes (best direction), Jones (best actress) and Lenox (best featured actress). Shanley also won the Pulitzer Prize for the play. The only newcomer in this cast is Joyce. McGarry understudied Father Flynn in New York.

The Ahmanson is not kind to this play; too much sound is swallowed and too many lines lost in its cavernous interior. Joyce in particular needs to speak louder to be heard.

Doubt, similar to David Mamet’s Oleanna in the he said/she said presentation of an issue, should inspire the same noisy post-show discussions about who is right, and is worth seeing if only for that.

Doubt plays through Oct. 29 at the Ahmanson Theatre in Los Angeles. Shows Thursday through Saturday at 8:00 p.m. and Sunday at 7:30 p.m., with matinees Saturday and Sunday at 2:00 p.m. For tickets, call (213) 628-2772.

Bach at Leipzig

Bach at Leipzig has almost nothing to do with the great composer, except that his existence disquieted and annoyed his competitors.

Playwright Itamar Moses uses auditions in Leipzig in 1722 for the post of kantor (organ master) of the St. Thomas Church as his pretext for imagining what six also-rans might have said and done to and for each other as they waited to play.

If you’re looking for something historical, this isn’t it. Bach at Leipzig is an odd combination of old jokes, verbal slapstick, low humor and disquisitions on the nature of Lutheranism, craftsmanship vs. innovation and the nature of choice, all tumbling from the mouths of six stunningly-clad 18th-century gents who want that job. (It seems evident to me that the seventh, a silent character named The Greatest Organist in Germany, is J. S. Bach, though other critics disagree. Decide for yourself.)

I can’t begin to keep them all straight, because “every German musician who isn’t named Johann is named Georg” and there are three of each. Suffice it to say plots, conspiracy and betrayal are all part of the evening’s entertainment.

Moses has a Stoppardian way with words, but at 29 doesn’t use them as well.

Bach at Leipzig is long (2 hours, 20 minutes) and talky and fascinating only in spurts, though some of those spurts are wonderful, such as the discussion of the structure of the fugue (illustrated by the actors in a very amusing bit). One of the problems is that the skid from a high-minded discussion of art too often ends up in an old joke (“I went to a concert and was transported. I fell asleep and woke up in Turkey”).

I nodded a bit too, but woke with a start when Erik Sorensen’s Steindorff, who had been abandoned in the woods by another character, shows up nearly naked and caked in muddy leaves. Moses’ play could use more of this.

Bach at Leipzig plays through Oct. 15 at South Coast Repertory Theatre in Costa Mesa. Shows Tuesday through Sunday at 7:45 p.m., with matinees Saturday and Sunday at 2:00 p.m. For tickets, call (714) 708-5555 or visit www.wcr.org.

|

|

Copyright © 2003-2025 Uptown Publications