-

- U.S. House passes bill to add attacks on gays to hate crime law

- Rudy Giuliani seen as unifying candidate among gay Republicans

- Gay sailor serves after being called back to duty

- Amaechi: ‘I underestimated America’

- McGreevey enrolls in program to contemplate priesthood

- Defender of abstinence resigns amid allegations of prostitution

- National News Briefs

- World News Briefs

health & sports

Fit for Life

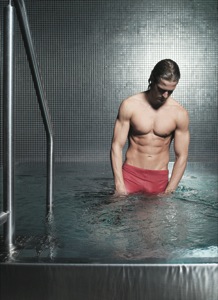

Hard core: more than meets the abs

Published Thursday, 10-May-2007 in issue 1011

Trivia question: What do Keira, Brad, Janet and Matthew all have in common? Well, yes, they’ve all achieved celebrity status. However, most recently they were placed on a list of those stars with “fab abs.”

Perhaps the most sought-after physical feature among regular gym goers, the secret to a strong, tight midsection goes far beyond that superficial layer of tissue we’re all very familiar with. I’m talking about the often-neglected muscle that wraps around one’s midsection that is responsible for a great deal of the body’s stability and mobility. The abdominals are the origin of all movement and can mean the difference between chronic back pain and functional freedom. Sure, a six-pack looks great, but those abs will mean nothing when you throw out your back trying to pick up your dog. By training your core, you kill two birds with one stone: Develop spinal stability for optimal function and reduced potential for pain and injury, all while tightening and toning that holy grail of physical fitness.

The bulging ab

Have you ever been to the beach and seen a fit-looking guy or girl sporting a six-pack, but the belly still protrudes over those board shorts? The abs are clearly defined; however, the deep tissues are most likely weak and thus incapable of preventing the excess spillage.

To get a better idea of what I mean, sit or stand up tall and contract your abdominal muscles so as to bring your belly button in toward the spine. (Some of you may be all too familiar with this maneuver.) Did that jelly roll suddenly become a jelly bean? That’s because the weakened innermost musculature cannot resist the pulling and pushing forces caused by the superficial layer of fat and the inner contents of the abdomen. Basically, the belly fat tugs on the core while your guts push it out. A strong core will hold everything in place and will give the appearance of a flatter, leaner torso.

The pain, the pain!

The human body is much like a tree providing support to its limbs. Without a solid trunk, the weight of the branches would surely cause the tree to buckle under pressure. With regard to the human body, core weakness tends to manifest in chronic back pain and/or injury, balance issues and decreased coordination. And, according to Portia Page, a STOTT Pilates certified instructor, strong arms and legs won’t move properly without a strong core. “Back pain is a common problem today,” she says. “However, if you are using your core effectively, you won’t have movement problems that lead to pain.” Research supports Page’s statements; current studies support the inclusion of core strength and stability programming into an exercise routine for enhanced rehabilitation and injury prevention. For example, if you were to build a three-story structure, you wouldn’t sandwich a gob of clay between the bottom and top floors; the structure would surely collapse. The same goes for the body. There’s really no point in building a huge upper and lower body without providing a solid foundation for them.

Consider this: According to the April 2007 issue of the Strength and Conditioning Journal, a spine without supportive musculature will buckle under loads as small as 4.5 pounds (lb). Further, walking puts about 31 lbs of pressure on the spine; bent-knee sit-ups can add up to 740 lbs; and a 200-lb athlete performing a half-squat with a 230-lb barbell will be placing 2,000 lbs of pressure on the low spine. These are monumental forces that require utmost support from area tissues. Without adequate strength and endurance, the potential for serious injury increases exponentially.

The abdominal crunch

The mainstay of traditional abdominal exercise, the crunch, comes in a variety of forms. From the basic bent-knee version to the lifted-leg, opposite-elbow-to--opposite-knee-with-a-triple-Lutz-jump crunch, exercisers and professionals have come up with many ways to work the rectus abdominus (the famous six-pack). Unfortunately, many people perform the crunch incorrectly and inadvertently activate a completely separate set of muscles.

According to research, the basic crunch should only be performed to about 30 degrees of movement. After that point, the hip flexors – overly tight muscles in the groin area that are responsible for lifting or moving the leg forward – take over and reduce contracture of the abdominal muscles. Most people go far beyond this very small amount of movement thinking that more movement translates into a more effective exercise. In fact, the opposite actually takes place. Activating the hip flexors can cause them to shorten, which will force the pelvis to dip forward. This forward dip will then lengthen the abdominals, making them weaker and more prone to bulging. Then the low back arches beyond neutral position, which places excess strain upon area soft and hard tissues. Over time, the body’s structures will experience abnormal wear, increasing risk of injury and reduced function. Here are tips for performing a crunch:

Don’t go beyond 30 degrees above the hips.

Think of lifting the shoulder blades vertically from the ground instead of rounding the upper back.

Actively contract all of the muscles in the abdomen throughout the duration of the movement by drawing the belly button toward the spine.

Try performing crunches on a stability ball or BOSU Balance Trainer. Allow the upper back to wrap around the ball for greater range of motion, since the start point is below the hips.

Treat the abdominal muscles just like the other muscles of the body. Perform several sets of 10-12 repetitions once or twice per week instead of hammering them day after day. If you’re able to polish off properly executed reps, increase the intensity by adding weight. Then take a few days off to allow the muscle to rest and grow.

There are a variety of methods for integrating core stability and strength exercises into your regular routine that won’t require any extra time, just a slight tweak to what you’re already doing. For example, a push-up is an excellent full-body exercise that requires a great deal of spinal stabilization. The key, however, is to attempt to maintain a straight line from the back of the skull to the heel. This means keeping your abs tight to keep the belly from sinking and the low back from arching. Another way to engage core musculature is to eliminate all benches or seats. Instead of sitting down for a dumbbell shoulder press, stand up, suck in the belly button and perform the exercise. Not only will your core become stronger, but more muscles are involved and the overall intensity increases, which means greater strength and more calories burned. According to Page, integrating a stability ball, medicine ball or BOSU Balance Trainer into the workout adds instability, which requires greater core strength. “Also try lifting one foot off the floor while performing a standing exercise,” she adds. “Or maybe come up onto the toes during a bicep curl. If the core is activated correctly, you should be able to sustain your balance.”

Improving the stability of the spine is of utmost importance for long-lasting functional capacity and greater quality of life. Taking simple steps to activate the core musculature will have you on the fast track to injury prevention, increased overall fitness and even that coveted washboard stomach. Check back next week for a sample core workout. Until then, happy training!

Have a health and fitness question? E-mail Ryan at editor@uptownpub.com and the answer may be featured in an upcoming issue.

|

|

Copyright © 2003-2025 Uptown Publications