-

- New York gives away condoms, offers AIDS education to seniors

- Same-sex marriage friends, foes hail domestic violence ruling

- Model-dancer sues nightclub

- Washington same-sex couples line up to register as domestic partners

- Washington interfaith group files brief in Iowa same-sex marriage case

- Man must pay alimony to wife despite her domestic partnership

- National News Briefs

- World News Briefs

feature

Hillcrest Centennial: heralding the past, forecasting the future

Published Thursday, 02-Aug-2007 in issue 1023

At noon today, Hillcrest residents will gather to celebrate the neighborhood’s centennial. Yet, as they fork up slices of birthday cake at the bustling intersection of the historic village’s Fifth and University avenues, the specter of the future looms – just two blocks to the east, 301 University, a proposed 12-story, $65 million mixed-use complex, seems to sneer “Let them eat cake” at slow-growth San Diegans.

Although it is said that the only constant is change – something San Diego’s gay and arty Mecca certainly has seen its share of – it is hard to fathom what the man considered to be the founding father of Hillcrest, William Wesley Whitson, would have made of the half-empty buses grumbling past the spot where, on Aug. 2, 1907, he opened a wooden shack to sell tracts of land (its prominent sign dubbing the area then considered part of University Heights, “Hillcrest”). How also might Whitson (who would today be 142-years-old) react when invited to a bar mitzvah for the son of lesbian homeowners living on a sliver of the 40 acres he purchased for $115,000? And what would he make of the fact that the median sales price for that lesbian couple’s single-family Hillcrest home is today $730,000, almost seven times what he paid for the whole Hillcrest kit and caboodle?

In 1993, current state Senator Christine Kehoe became the first openly gay person to represent Hillcrest on the San Diego City Council. The upstate New York native recalled the neighborhood’s allure when arriving in San Diego in the early 1980s.

“Having been raised back east in a smaller city where there was really still a downtown and you’d go from store to store, it was very familiar to me,” said Kehoe, who in 1984 took a job as editor of the Gayzette, located on what is now part of the Whole Foods parking lot.

“It’s an interesting neighborhood,” she said. “People who live in La Jolla or Del Mar or points north love being able to go out to dinner and then go see a foreign film…. It’s never been only a gay neighborhood to me. It’s a great mix of people.”

Though San Diego real estate speculators had laid out subdivisions by the 1870s, by the turn of the century the area that would become Hillcrest was still largely used to hunt jackrabbit, with a few houses and Joseph’s Sanitarium dotting the sparse landscape.

In 1906, Whitson, San Diego’s first coroner and a city councilmember, nabbed his 40 acres between First and Sixth avenues from the George Hill Estate, promptly subdividing the stone-covered mesa. At $115,000, it was a savory deal, considering that a neighboring parcel of a similar size reportedly sold for $300,000.

Whitson’s Hillcrest Company erected a sawmill that supplied lumber for some 3,000 homes. He would later move northward to help develop parts of Los Angeles, returning for a 50-year celebration at the age of 92.

Ann Garwood and business partner Nancy Moors, who publish the HillQuest community directory and founded the Hillcrest History Guild, are spearheading a series of centennial events this year, including today’s cake cutting and an evening barbecue social at the Joyce Beers Community Center (see sidebar for schedule).

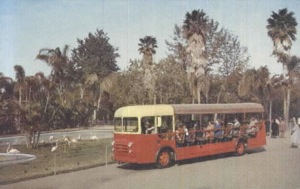

Garwood said the trolley that once ascended Fifth Avenue and ran east to west along University helped to sell the area and its now historic cottages and bungalows to future residents. “People began seeing this little building there with Hillcrest Tract Office on the top and then started calling this part of University Heights Hillcrest,” she said.

Within a few years, hundreds of houses and Florence Elementary School were established, and by the 1920s and 1930s, Hillcrest was a thriving commercial and residential district.

The bungalows and smaller single-unit family homes would prove ideal when the gays and lesbians set in motion a gradual gentrification of Hillcrest that began in the late ’50s and early ’60s.

Arriving in Hillcrest in the late ’50s or early ’60s, Dennis Quaid’s closeted character in the 2002 melodrama, Far From Heaven, would have found refuge in Hillcrest’s affordable old homes.

Leo Wilson, chair of the Uptown Planners and a longtime community activist, recalled slipping off to Hillcrest in his late teens in search of a simpatico network of people.

“I grew up in Mission Beach, but being a gay kid and just coming out back then you hung around Hillcrest, the park and those areas,” said Wilson, 53. “You wanted to have friends you could be totally open with, so it was a magnet for gay youth from everywhere. They just sort of showed up.”

While in 1990, 48 percent of Hillcrest’s population was between the ages of 22 and 44, in 1970, the majority of residents, about 48 percent, were still over the age 45.

“They used to say Hillcrest was in the ‘gay 90s’ – you were either gay, or you were in your 90s,” Wilson said. “This was one of those communities – and it happens everywhere, like in North Park – where the original residents got so old that it was time to turn over…. The community was sort of blighting, and you had gays moving in because they liked these older houses.”

Though Wilson dodged some of the most egregious police harassment toward GLBT San Diegans by about a decade, harassment is part of Hillcrest’s collective history, he said, just as were the violent attacks outside last year’s Pride festival.

“The police were awful back then,” Wilson said. “They used to go into the bars and arrest people for indecency if they didn’t have socks on. They used to come and do raids where people would have to go hide in the bushes.’

Amy Whitson, great great granddaughter of William Wesley Whitson, spent the first 16 years of her life in a house on Georgia Street. Though she has no idea how the patriarch of her family and of Hillcrest might have felt about the influx of gay residents, to her family they were just part of the fabric of their community.

“It’s definitely not an issue for the younger of the Whitsons,” said the 27-year-old Rancho Penasquitos resident, who will be at the cake-cutting ceremony with her two children and grandparents. “I still go there and eat at places like Hamburger Mary’s…. That’s where my childhood memories are. We have big books of pictures, black and white, from early 1900s, of Mission Valley and the surrounding areas of Hillcrest.”

As executive director of the Hillcrest Business Association in the 1980s, Kehoe worked to reinvigorate the deteriorating neighborhood, while striving to maintain what her predecessor at the association, Joyce Beers, deemed “San Diego’s most walk-able neighborhood.”

A prime opportunity arrived in the 1990s in the form of the $70 million Uptown District development at University and Vermont. Today the site of the Ralph’s and Trader Joe’s, the 14-acre, mixed-use retail center and residential development replaced older apartments and a vacant Sears store that closed when shoppers shifted to Mission Valley’s mall culture.

Like 301 University, which is currently embroiled in litigation, not everyone initially warmed to the Uptown District concept.

“A lot of people were concerned that it was going to be too dense and that it would destroy the character of Hillcrest … [but] it completely changed the neighborhood and modernized it,” Kehoe said. “It gave it a shot in the arm.”

“Whatever shape Hillcrest takes in the next 10 to 20 years. Ann Garwood and Nancy Moors plan to be there to document it. The two formed the Hillcrest History Guild in 2005, collecting bits and pieces of the neighborhood’s history, which they compile on their Web site, www.hillcresthistory.org.” In 2000, current 3rd District Councilmember Toni Atkins replaced Kehoe as Hillcrest’s council representative. Moving to San Diego in 1985, Atkins was smitten with Hillcrest’s bookstores and the homey Crest Café on Robinson. She agrees that the Uptown complex helped revitalize the business area when it opened in 1990.

“There was a period of growth in Hillcrest back when Uptown was completed,” Atkins said. “There was a huge effort toward small business development and support…. That lent to the village feel.

“I think what’s happening now,” Atkins said, “is that for too many people it feels like we’re moving away from that village because of some of the development that had been approved.”

Though most of the taller structures have been going up in and around Banker’s Hill over the past few years, the 140-unit Atlas Hillcrest condo project next to Hash House on Fifth Avenue is too large and close to the center of Hillcrest for some residents’ comfort.

“If you go further north you’ve got the development that’s started to occur on Washington Street in Mission Hills,” Atkins said. “So you’re feeling [development] from the North; you’re feeling it from the South. I think it’s a legitimate concern on the part of the residents of Hillcrest: ‘What is this impending encroachment of tall buildings going to do to our village feel?’”

City planners won’t start working on a revision of Hillcrest’s community plan (which allowed for the approval of 301 University) until next year, and it likely won’t be finished until 2009 or 2010. To stave off a spree of unchecked development while the new plan is being drafted, the Uptown Planners has proposed that an interim height limit of 65 feet, about six or seven stories, be established.

“The plan that was put into place over 20 years ago is something that the community embraced at that time and obviously supported in large part,” Atkins said. “The vision can change.”

Bob Grinchuk, a past president of the Hillcrest Business Association and a member of the Uptown Planners board of directors, owns the Wine Lover on Fifth Avenue and the Casa Grande apartments on University with longtime partner, Reuel Olin. He said he believes “intelligent growth” is good for Hillcrest.

“A neighborhood can’t shut down; it can’t restrict growth,” Grinchuk said, “Because if it does it will simply die. One of the things that a lot of people forget is that 20, maybe 25 years ago, Hillcrest was a dying community. People moved in, they renovated houses and made it another place. I think this is just another manifestation and another generation of change.”

When Grinchuk and Olin first purchased the Casa Grande, near the then vacant corner of Park Boulevard and University Avenue, the area was regarded as a slum, he said, the adjacent LGBT Center still a union hall.

“It’s all changed because new things have come into the neighborhood,” Grinchuk said. “It’s been, in many ways, revitalized by growth…. We’re getting businesses along University Avenue that we couldn’t have anticipated 10 or 15 years ago. The procession of businesses is moving from Richmond all the way up to Park.”

Regarding concerns that projects such as 301 University will alter the character of Hillcrest, Grinchuk questioned precisely what that character is.

“A lot of the people who talk about character in the neighborhood are newcomers,” Grinchuk said. “The character they cite is something that’s intangible, something that I think they’re bringing to the neighborhood or something that’s imaginary….

“I’m not opposed to 301,” he said. “It may be larger than some people like, but it’s going to bring new people into the neighborhood. The business community can’t survive if it doesn’t have people to go into its shops [and] restaurants.”

The community plan that allowed for 301 University is the same plan that prevented high rises from sprouting up in the area around Third Avenue, just south of Upas and along portions of Sixth Avenue, he noted.

“That’s the only way those neighborhoods have been preserved. Lots of people criticize the community plan and in lots of ways it’s outdated, but there’s still many parts of it that are valuable and need to be preserved.”

Threats to Hillcrest’s aesthetic allure are more posed by boxy condo and apartment complexes that have gone up during the last 10 to 15 years, Grinchuk said.

“The Historic Resources Board … has never been especially interested in preserving residential neighborhoods that are not of historic capital age,” Grinchuk said. “Until recently, it’s been a good collection of many workingmen’s cottages…. These have to be preserved and I don’t think the historical resources site board, when it comes to looking at putting together a historical district, is interested in a neighborhood that is not posh.”

Grinchuk points to a slate of apartments along Park Boulevard, between Balboa Park and Robinson Avenue, that were built in the early 1900s, often referred to as “apartment row.”

“There are these wonderful, early 20th century apartment buildings, … the kind of development that was fueled by [the introduction] of streetcars. They could go in a nanosecond, because nobody is interested in them,” Grinchuk said.

Marlon Pangilinan, a senior planner in the city’s development department, will oversee the update of Hillcrest’s community plan. Pangilinan said there is concern for adding stronger guidelines to protect Hillcrest’s historic buildings.

“That’s a big deal in terms of … new projects coming and proposing demos of existing structures,” he said. “People want some more guidelines in terms of maintaining that historic character. It’s one of those things that gets streamlined or falls through the cracks.”

Wilson said he feels a good part of the character some are looking to preserve in Hillcrest came from development projects such as the Uptown District and the Landmark Theater complex, which brought with them upscale eateries, boutique shops and further gentrification.

“The irony is that what the Hillcrest people are trying to preserve now was created about a decade ago,” Wilson said. “It didn’t exist before then. Prior to that it was a chummy little village, but it was sort of a blighted area.”

However, Leo believes adding more high rises to the area could destroy the village, transforming it into an extension of downtown San Diego.

“You go to any major city that people brag about as a wonderful urban environment — Seattle, San Francisco, Boston — they limit the height of buildings and they control the design. In San Diego there’s no control. Basically you’re able to build what you want to build…. We’re getting boxy buildings built everywhere in Hillcrest….

“You can go down these narrow streets in Hillcrest and [envision] a canyon of just modern glass and steel. What’s happened at that point is that the Hillcrest that existed for 100 years has been wiped off the map.”

Wilson said the height limitation advocated by Uptown Planners, as supported by the city council, would make exceptions for good design.

“We’d have to work out what they would be and that’s going to be a big negotiation,” Wilson said

Whether approaching the intersection of Fifth and University from the north, south, east or west at virtually any time of the day has the feeling of rush hour in Los Angeles.

The gridlock is so bad, Wilson said, that police answering calls are advised to take an alternative route, rather than going through Hillcrest.

In 2005, Caltrans gave the city and San Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG) $432,000 to analyze traffic and transit along Fourth, Fifth and Sixth avenues in Banker’s Hill and Hillcrest. With the funds, SANDAG developed the Hillcrest Corridor Mobility Study. One proposed outcome of that project has Wilson and other Banker’s Hill residents up in arms. It proposes removing lanes of traffic between the four arteries to add designated bus lanes.

“The city wants to basically try to put bus lanes there with the assumption people will take the bus,” Wilson said. “It won’t work. Bus rider-ship is falling in San Diego.”

Wilson pointed to a recent Los Angeles Times editorial that blasted the city for wasting billions on rapid transit busses, noting that an increase in mass transit use from 4.5 to 4.6 percent was more than offset by the increase in people coming to live and shop in the area who traveled by car.

Instead of investing in expansion of the trolley line or another light rail system, Leo noted, the city has expanded its bus system, but people who can afford to live in Hillcrest are less likely to take the bus, he said.

“They went with these glorified buses that get struck in traffic,” Wilson said. “There’s no major city in the country that’s been this ridiculous…. The people in my neighborhood, they’ll walk downtown before they’ll get on a bus.”

George Franck, a retired transportation and land use planner with SANDAG, is today a planner for the Uptown Partnership, a non-profit corporation contracted by the city to manage its parking meter program in Hillcrest and Mission Hills. At SANDAG, Franck worked on a previous traffic-calming project on Fourth through Sixth avenues, and is today involved in the Hillcrest Corridor Mobility Study.

“Certainly, poorer people tend to ride the bus,” Franck said, noting the city’s inclusion of a smaller shuttle that runs from Presidio Park through Mission Hills and Hillcrest to downtown San Diego. “It’s a small vehicle. It only runs about once an hour, only during daylight hours, but it’s a way of trying to get people who wouldn’t ride on a 30-foot, 40-foot regular bus to use transit. It’s not as intimidating as a big bus; it’s nicer to the neighborhood and it doesn’t make as much noise.”

However, Wilson said switching to bus travel is a lifestyle change people in Hillcrest are not prepared to make.

“You don’t have a life. You can’t go to the grocery store and buy your groceries. You can’t guarantee that you’re going to be there on time. I mean this is a fantasy…. SANDAG to me is a group that is on an LSD trip…. What can make this bad is if they would use their proposal here to say we don’t need to mitigate traffic anymore, or be concerned with density, because everybody will start using the bus.”

Parking studies conducted by Uptown Partnership show a need for between 450 to 700 additional parking spaces in Hillcrest during the next 20 years, and at least 200 in the next five years, Franck said. As currently drafted, plans for 301 University would add an additional 121 paid, underground spaces. Due to the city’s financial problems, Franck said development projects such as these are likely the best source to generate additional parking.

“This is kind of an unpopular project, but 301 University was the first example of trying to do [that],” Franck said. “The city has to be able to bond in order to build those kinds of facilities, and because of the financial problems we’ve not been able to do that. Cooperating with developers is the way to get around that until the city can bond.”

Franck downplayed concerns that future development projects such as 301 University will add to traffic congestion in the area.

“There [was] a lot of concern when the ballpark went in downtown that there would be a lot more traffic and there hasn’t really been,” he said. “Given the amount of redevelopment we’ve had, it seems like the traffic should have grown more than it has. I think a lot of what’s happening is that people are much more pedestrian oriented in Hillcrest than they were 20 years ago. People are walking places, because it’s hard to find a parking place, and for a whole bunch of reasons.”

However, he concedes, traffic will continue to increase in Hillcrest. The mobility study, to be completed in a matter of months, should indicate by just how much.

In the meantime, don’t look for the San Diego’s little red trolley to come sailing up the hill to ease Hillcrest’s traffic woes, Atkins cautioned.

“They denied and ruled out the trolley going up I-15 through my district in Mid-city which would have been a real good idea,” she said. “People had talked about it going down El Cajon Boulevard. No, I don’t see that happening in my lifetime.”

While everyone may not be in accord with the pace and shape of development, Atkins agrees that in San Diego’s cash-strapped state, striking a bargain with developers may be the most expedient way to get the parking and green spaces desired.

“The upside is we have developer impact fees that have been raised pretty significantly. The community supported raising those fees several years ago, and they were smart to do that because they have reaped the benefits of millions of dollars because of the development to do some of those improvements and parks,” Atkins said. “At the same time, the downside is that it took development to get development impact fees.”

Much of the development fees that have benefited Hillcrest have been collected from projects in Banker’s Hill and Mission Hills, Atkins noted.

“We’ve used money for gutters and storm drains and various not-so-glitzy or sexy projects like that, but we’ve also used money on the pop-outs on University Avenue in Hillcrest. We’ve used some of that money to help with the median in front of the DMV and the old Center and that church on Normal Street.”

Speaking of development, Kehoe said she’s still holding out hope that old George Pernicano will unload his dilapidated and boarded Casa di Baffi restaurant on Fifth Avenue.

“That’s a terrific piece of property,” Kehoe said. “It could be an urban mall … a public space, a theatre space. If I had a nickel for every time I heard that Pernicano’s was going to be redeveloped, you and I could both be living on an island off the coast of Mexico.”

Whatever shape Hillcrest takes in the next 10 to 20 years. Ann Garwood and Nancy Moors plan to be there to document it. The two formed the Hillcrest History Guild in 2005, collecting bits and pieces of the neighborhood’s history, which they compile on their Web site, www.hillcresthistory.org.

“We have little funds, but a lot of creativity,” Garwood said. “We’ve continued to expand the Web site to build a virtual museum that can be shared for free – not only with the community, but with people throughout the city, the state, the country and the world who want to know a little bit more about our community and its history.”

Garwood said she was inspired by the tragic loss of historic records that were destroyed when the Hillcrest Business Improvement Association’s offices caught fire a few years back.

“Nancy and I are both on the board of the HBIA now, but even at that time we realized what a loss that was,” Garwood said.

Moors and Garwood hope to use some of the money they raise from the centennial events to hire a part-time executive director who can help compile the information. They are also seeking help from volunteers and students willing to compile oral histories of longtime Hillcrest residents.

“There’s a lot of elderly people in our community that almost reach back that hundred years that have memories, or their mother was here at the turn of the century, but they’re quickly passing, and what they have in their heart and their mind is going with them,” “We’d love to get more volunteers that might want to come in and help do anything [they can] to move the effort forward,” Garwood said. “If people have gone through Hillcrest at any time in their life and they’ve got a story that they can share to pass on to future generations about what Hillcrest was like at that moment in their lives, that’s something that you can’t go out and buy.”

|

|

Copyright © 2003-2025 Uptown Publications