Arts & Entertainment

Out of the closet, into the locker room

Published Thursday, 13-Jan-2005 in issue 890

One of the last great bastions of macho homophobia is the male locker room. Like the military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy, in American professional sports — particularly the big four team sports of baseball, football, basketball and hockey — the question itself seems to be cause for alarm.

When rumors swirled in 2002 about New York Mets all-star catcher Mike Piazza’s sexual identity, he felt it necessary to hold a press conference to state his heterosexuality for the record. “I’m not gay,” he said at the meeting. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, he was quick to add. “In this day and age,” said Piazza, “it’s irrelevant. I don’t think it would be a problem at all.”

He may have been right, but we can’t know for sure, since no professional baseball player has ever publicly acknowledged his homosexuality while still in uniform. Athletes who choose to come out face possible loss of commercial endorsements, which might be the least of a player’s worries among fears of public scrutiny, derision and even physical harm. Only two major league baseball players, Glenn Burke and former Padres outfielder Billy Bean, have come out following retirement.

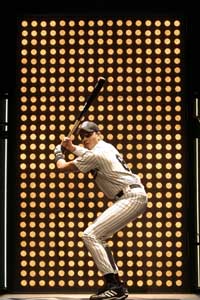

This situation makes Richard Greenberg’s Take Me Out not just timely, but perhaps prescient. The Tony Award-winning play opens at The Old Globe on Jan. 20 at the end of a West Coast tour that began at the Seattle Repertory Theatre and features the same cast. The tragicomedy, which premiered in 2002, deals with what happens when a major league baseball player comes out of the closet, and how that announcement ripples through the team, the league and the nation.

Darren Lemming is a hot young baseball player for the fictional Empires, a team reminiscent of the New York Yankees. He has just signed a huge long-term contract and is headed for the Hall of Fame. He’s described as that rarest of athletes, a five-tool player: one who excels at throwing, hitting, stealing bases and fielding, and has a high batting average. He’s also just surprised teammates and fans by disclosing his homosexuality at a press conference.

“He thinks nothing will happen,” explained M.D. Walton, who plays Lemming. “He’s at the top of his game; he’s a golden boy with egotistical charm.”

Walton compares Lemming’s popularity to that of Derek Jeter. “Just imagine if Derek Jeter had come out of the closet, and see how that would resonate throughout the ball community and the community in general,” said Walton.

Lemming’s charm, it turns out, isn’t enough to save him from the taunts and malice of less open-minded players on the team. When a hateful relief pitcher — think real-life homophobe John Rocker – named Shane joins the team, it sets in motion the story’s final tragedy.

The team’s discomfort with Lemming’s revelation is felt most strongly in the locker room, where butt-slapping jocularity mixes with machismo and unclothed immodesty in close physical quarters. The play features a few much-discussed hunky nude scenes, including a shower scene with running water and full frontal nudity. But Walton insists all the bared flesh isn’t gratuitous.

“The nudity is appropriate for the show, especially with the issue of homosexuality,” said Walton. “That’s what baseball players do. It’s reality thrown in the audience’s face — they get to see it in three dimensions. It creates tension.”

But Take Me Out is about more than just homosexuality, and Walton is confident that the play will appeal to statistic-rattling baseball fans as well as those who can’t tell a pop fly from an RBI.

“[Greenberg] doesn’t just deal with homosexuality,” says Walton, “he deals with racial politics, identity politics, friendships, religion, everything — which makes it so appealing.”

In the play, Lemming is biracial, and Walton himself is part black, part Mohawk Indian and English Dutch. Also on the multiethnic team are two Latino players and a Japanese player. Baseball, said Walton, is a microcosm of America.

“They call baseball the American pastime time, and it’s so significant to lot of people in America,” said Walton. “Being from New York, surrounded at a young age by the Yankees, you see how magnetic baseball can be to those diehard fans.”

Baseball’s mass appeal, its iconic stature in American culture and its sense of democracy may be why gay playwright Greenberg chose to use it as a background for his play. Professional baseball broke the color barrier in 1947 when Jackie Robinson joined the majors, and lineups are now filled with players of color. There’s no question that integration in baseball and other sports improved the level of play and won over new fans. But Robinson did more than just integrate baseball. His entry into and great success in the majors had far-reaching political implications, and paved the way for the civil rights movement a decade later. It’s likely that breaking the gay barrier in baseball would similarly have an important effect on the gay rights movement.

But is major league baseball ready for an openly gay player?

In a 2004 poll by the Tribune newspapers of 750 major league baseball players, 74 percent said it wouldn’t bother them to have a gay teammate. While “not being bothered” isn’t quite the same as “accepting and supporting,” the survey is positive, suggesting that the sport might not be so hostile toward an openly gay player. Greenberg’s version of things in Take Me Out is also optimistic.

“Every character has to deal with an issue; every character grows throughout the show and finds himself in a certain way. They find clarity of identity,” said Walton. “The message for Darren is that there’s hope for him.”

Take Me Out opens in previews Jan. 15 and runs through Feb. 20. Tickets are $19-$55 and available by calling (619) 23-GLOBE or visit www.gaylesbiantimes.com for a link to the Old Globe Theatre’s website.

|

|

Copyright © 2003-2025 Uptown Publications