Arts & Entertainment

The beauty behind Man Booker Prize winner Alan Hollinghurst

Published Thursday, 31-Mar-2005 in issue 901

The Man Booker Prize is Britain’s most prestigious literary award. The reason is not hard to understand: money. The prize, at its foundation in the mid-‘80s, was very well-endowed by an important futures trading firm, and has been able to maintain complete independence. Its jury consists of a distinguished mix of novelists and of society, who both accept nominations for the award, or independently choose to include an un-nominated dark-horse candidate in their selection. It is open to writers living in Great Britain, Ireland and the Commonwealth. There are special prizes for writers in Russian and African literature. Each year the Booker committee selects one book as a prizewinner, and a number of novels are short-listed. These books represent the committee’s selection of the best novels published in Britain and the Commonwealth in that year. The prize is intended as a guide to help readers select what to read among the approximately 10,000 novels published yearly in the anglophone world.

The prize last year aroused some extra attention because it went to an openly gay writer, Alan Hollinghurst, who writes about gay life. Obviously, Hollinghurst is not the first gay writer to receive the prize, or the first writer ever to write about gay life, but the way in which he does so is a departure from the traditional treatment of homosexuality in British literature. He does not, in the first place, treat homosexuality as in any way grim, fated or doomed. The hero of his first novel, The Swimming Pool Library, in fact enjoys an unusually privileged position. His name is Will Beckwith, and he is young, extremely handsome, wealthy and heir to a title.

Beckwith, in short, has it all. He has such a grand conception of himself that he has ceased working and spends his days sleeping late, then cruising for casual sex in the parks, pubs and clubs of London. Hollinghurst is no politically correct hypocrite when it comes to describing modern gay life.

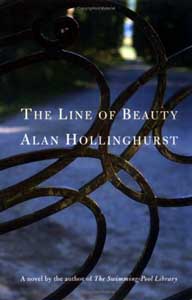

He is well aware that the image-makers of gay life, like the image-makers of heterosexual life, emphasize an ideal of shallow hedonism to persuade us all to adopt a lifestyle of carefree consumerism. It is exactly this lifestyle that Hollinghurst skewers in his novel The Line of Beauty, which won the Booker Prize. The Swimming Pool Library took place in the early ‘80s, just about the last summer before the AIDS epidemic, when the gay scene enjoyed an “anything goes” attitude towards sex. The Line of Beauty also takes place in the ‘80s, during Margaret Thatcher’s economically uninhibited Britain, when the goal of everyone seemed to be to enrich themselves by whatever means necessary. Nick Guest, the hero of The Line of Beauty, has no share of Beckwith’s privileged position. He is a man from a poor background who attends Oxford on a scholarship. He is naturally fascinated with Toby Fedden, the handsome son of the rich member of Parliament, Gerald Fedden. Guest is gay, but only technically, having no sexual experience at the start of the novel. Guest goes to London to visit Fedden’s family, and proceeds to fall in love with the whole Fedden family and their self-assured, opulent style of living.

Hollinghurst excels at this sort of description: the excitement of a young man entering into a charmed circle that will seemingly open a world of possibilities to him, mixed with the thrill of sexual experimentation. It is a sure formula in British fiction.

Evelyn Waugh used it to great effect in Brideshead Revisited, only now Hollinghurst can openly exploit the homoerotic elements of the plot, whereas Waugh had to repeatedly deny any overt homosexuality in his characters.

The Line of Beauty episodically follows Guest’s adventures in society. One chapter shows us Fedden’s 21st birthday party, another chapter deals with cruising at a gay swim club. We also see a Sunday morning in the Fedden household, a holiday in France, the Eurotrash lifestyle of the Lebanese multimillionaire Wani Oura and even a personal visit by Mrs. Thatcher herself. We are given a comprehensive view of life at the top in Thacherite Britain.

As amusing as all of this is, Hollinghurst is not merely catering to his readers’ voyeuristic fantasies. The novel conveys a moral lesson that is impossible to overlook. As we follow Guest’s career, we see him change from a sweetly innocent college-boy virgin into a coarse sexual predator with an out-of-control coke habit. Gerald Fedden’s political career and fortune are lost to scandal and corruption.

Hollinghurst, with his scathing view of society and the questionable nature of social success, is writing in a grand tradition of British literature that extends from the Thackeray of Vanity Fair to the Waugh of Brideshead Revisited. It is well-known territory to Hollinghurst. The Swimming Pool Library, Hollinghurst’s first novel, confronted Will Beckwith with the elderly Lord Charles Nantwich, who had spent his life in the British Foreign Service governing a large tract of Africa. Nantwich’s life of humane service is contrasted with Beckwith’s life of obsessive sexual pursuits. Hollinghurst is a very erudite novelist who is familiar with British culture and history. In both The Line of Beauty and The Swimming Pool Library, he contrasts the solid contributions of gay people in the past with the twittering “Queer Eye for the Straight Guy” role that gays are assigned in today’s culture. He reminds the gay community that there is indeed such a thing as gay history, and it is a proud and honorable history. He teaches society at large that gays have always played a central and important role in society. He proves by his intricate, complex and enjoyable novels that one of the best novelists working today is a gay man. He is a man who deserves great respect. The Booker Prize is well-deserved.

|

|

Copyright © 2003-2025 Uptown Publications