feature

The gay vote:

How big is it, how strong is it, what is it?

Published Thursday, 07-Oct-2004 in issue 876

This is the type of article that is guaranteed to irritate everyone and please no one: It is an article about politics.

More specifically, it is an article about the rise of the gay voting block. Assuming that anyone takes notice of it at all, it will generate two schools of opinion, or – if its readers feel strongly enough about it – it will generate two types of letters to the editor: Liberals will write in to complain that it is too soft on Republicans, and conservatives will write in to say it is another example of the liberal, Democratic bias of the press.

This article, for what it’s worth, is based on the opinion that both Democrats and Republicans have made their contributions to the movement known as gay liberation, just as both parties have for the most part bitterly opposed it. It argues that neither party has done anywhere near enough to recognize or reward the contributions and loyalty of its gay supporters; and finally, it asserts that the gay vote has been more critical than either of the parties or the mainstream media has been willing to admit.

Fits and starts

A new era in gay politics began with a fundraiser in Los Angeles in May, 1992.

When it took place, the Stonewall Riots were nearly 30 years in the past. The vanguard of lesbians and gay men had been insisting on their right to live their lives in the open according to their conception of sexuality for three decades. Feminism, gay liberation and the AIDS epidemic, which was then entering its second decade, were challenging traditional ideas of gender roles and the position held by America’s sexually-defined minorities in national life. AIDS forced people out of the closet; it permitted gay people of every description no other option than to organize and publicly demand their rights to information, prevention and healthcare. The fight against AIDS demonstrated to the nation that lesbians and gays were capable of tremendous feats of self-organization and political strategy that resulted in solid political victories.

“Today, GLBT voters are in fact the most dependable Democratic voting block after the African-American and Jewish communities.” Nonetheless, before the preliminaries to the presidential election in 2000, the political energies of the gay and lesbian organizations, when they had been allowed to express themselves at all, had been concentrated on the more narrowly defined homosexual issues such as healthcare and protection against discrimination in employment, housing and the right to assembly.

The limitations on gay political expression were not an expression of apathy or disinterest on the part of gay voters. Voters were simply not allowed to express themselves as members of a gay voting block. The Democratic National Convention in 1972, when the presidential candidate was George McGovern, included openly gay delegates. McGovern was willing to meet with them, and also expressed himself in sympathy with their goals of greater toleration. When McGovern was crushingly defeated by Nixon in the general election, the Democratic party leadership blamed his supposed sympathy for the gay agenda for a part of his unpopularity. It became a rule of Democratic political life that the party could not only not touch gay issues, but that it should also avoid identification with any “special interest group” such as African-Americans, Hispanics, feminists or seniors. The Democratic Party was attempting to reposition itself as a party at the center of American politics – neither too far to the left or right. Bill Clinton was the heir and the epitome of this repositioning. The ban on involvement in gay issues remained so strong that when gay fundraisers offered to provide the Dukakis campaign with $1 million in contributions in 1988, his campaign declined rather than risk too close an identification with “the gay agenda.”

That brings us back to our fundraiser: When, in 1992, a mainstream presidential campaign publicly courted the support of the gay community, it was not a sign that the Democratic Party had returned to championing fringe groups; it was more a sign that gay issues were becoming a matter of national politics. It was certainly an indication of how successful the gay movement had been in mainstreaming itself.

A voting block is born

The Clinton campaign invited approximately 600 leaders of the Los Angeles gay community to a fundraiser that was widely covered in the press. It was a daring move on Clinton’s part. He was relatively new to the national scene, and risked being denounced as a supporter of the homosexual agenda. He faced the danger of antagonizing the Democratic voters in the Bible Belt as well as courting the wrath of Jerry Falwell and his cohorts. The risk paid off. Clinton raised more than $100,000 in this one fundraiser alone.

“I have a vision,” he told his assembled supporters on that occasion, “and you are part of it.”

The fundraiser introduced politically active gays to the practices of national politics in more ways than one. It was on this occasion that Clinton promised that, if elected, he would end the ban on gays in the military by executive order. He also claimed he would initiate a “Manhattan Project” for AIDS, referring to the successful government project headed by Albert Einstein during World War II, when the leading international nuclear physicists were brought together and given unlimited resources to develop the first atomic bomb. Clinton’s Manhattan Project would have organized leading medical researchers into an effort to develop a serum for AIDS. Neither of these promises were redeemed when Clinton took office. Clinton supporters claim he was thwarted in his intentions by the Washington, D.C., establishment and the Pentagon, while his critics claim that he had no intention of fulfilling his promises: that he would have said anything to gain the financial support of the wealthy Los Angeles community.

Money, as Jesse Unruh, the former speaker of the California Assembly, used to remark, is the mother’s milk of politics; beginning with 1992, the gay community proved that it could be counted on to deliver the wherewithal to run a successful campaign. However one views Clinton’s record on gay rights and AIDS, there is no doubt that he enjoyed the financial support of lesbians and gays across the nation. David Mixner, an openly gay man who was also one of Clinton’s most successful fundraisers, estimated that over the pre- and post-nomination periods, gay supporters donated around $3.5 million to the Clinton campaign.

While it was a groundbreaking move on the part of the Clinton campaign to publicly appeal to gay support, it was not a surprising move. Gay voters had been increasingly proving their clout in the political process for some time. The Human Rights Campaign (HRC) Fund, a political action committee dedicated to supporting candidates who are sympathetic to gay issues, contributed $528,000 to various congressional candidates between 1989 and 1990, and $712,000 between 1991 to 1992, at which time they ranked 42nd among all politcal action committees (PACs) in the nation in the amount of money donated.

The GLBT factor in politics that began with Clinton’s 1992 campaign marked an era of political influence that continues today. Exit polls that asked about sexual orientation estimate gay participation in the 1992 election at around 5 percent, a percentage that has remained steady in the last three elections. That makes the gay vote as large and as important as the Hispanic vote, and larger than the much-courted Jewish vote. Not only that, but the gay vote is concentrated in urban areas in swing states such as Illinois, Michigan, New Jersey, Ohio and Pennsylvania, as well as the large gay communities in New York and California. We are used to articles claiming that the Hispanic vote will remake the face of American politics. President George W. Bush has gone through the effort of making political speeches in Spanish to woo Hispanic voters; yet the gay vote, numerically as important and financially much more important than the Hispanic vote, is largely ignored in political post-mortems.

In spite of this, there is a conspicuous absence of public analysis of the gay vote – or the degree of a party’s indebtedness to it – by both the Republican and Democratic parties. Virtually no analysis has been published concerning the decline in gay support for the Democratic Party in 2002, the year that saw the election of an overwhelmingly Republican Congress. The Democratic Party has been forward in appointing individual gay members to positions of national importance, but behindhand in acting on issues that are important to the gay voting block, such as lifting the ban on gays in the military, or supporting the right to same-sex marriage. If the Democratic Party has done any investigation of the correlation between the decline in gay support and a decade of unfulfilled promises, it has not seen fit to publish the results.

At home with the Democrats

“The Republican establishment does not want to fight the conservative culture war, partly because they think it’s a losing fight but more importantly, they don’t believe in it.”— William Kristol, writing in 2000

Nevertheless, the Democratic Party, which has traditionally been the party of the labor unions and the party perceived as the more dedicated to securing civil rights for ethnic and immigrant minorities, has long seemed the more natural political home for GLBT activists. As early as 1972, during the campaign of George McGovern for president, the first televised addresses by an openly gay and an openly lesbian delegate – Jim Foster and Madeline Davis – were made to the Democratic National Convention. The strength of GLBT support during the primaries was recognized by McGovern when he included a plank in the civil rights section of the party platform that demanded an end to discrimination in housing and employment based on sexual orientation.

Jimmy Carter, in his successful 1976 bid for the presidency, actively courted the gay vote. He, like Clinton, made campaign promises that he was later unable or unwilling to redeem, but it was during his administration that 14 lesbian and gay activists were invited to the White House for the first-ever official meeting with the President, and he named the openly lesbian Jill Schrop to the National Advisory Council on Women in an official White House ceremony in 1979.

The Democratic Party seemed quicker to recognize the existence of a gay voting block able to organize and deliver the vote, as well as willing to help finance campaigns. The gay voting block, in short, had a solid influence on the outcome of elections, and Democrats seemed the more willing to honor that. It is not surprising under these circumstances that exit polls, which inquired about sexual orientation, always registered a much higher support for the Democratic Party over Republicans – generally at a margin of about three to one – among gay voters. GLBT voters supported Democratic candidates for Congress by margins of 61 percent in 1990, 77 percent in 1992, 85 percent in 1998 and 71 percent in 2002.

Today, GLBT voters are in fact the most dependable Democratic voting block after the African-American and Jewish communities. Even in years such as 2002, when gay support for the Democratic Party declined, gays do not necessarily vote for Republicans. Seven percent of the gay vote in that year went to Libertarian or Green candidates and about 19 percent went to Republicans. The famous 2002 presidential election saw gay support for the Gore/Lieberman ticket running at 70 percent, with Bush/Cheney taking 25 percent of the vote, and about 4 percent going to Nader.

And … that other party?

The Republican Party is known as the party of traditional values. This is generally interpreted in social terms to mean support for the heterosexual family unit, as well as a preference for a strong religious involvement in public life. Traditional values, as propagated by the majority of Republicans, seem to many to be implicitly incompatible with a gay lifestyle, and it seems safe to say that the majority of gay people have felt unwelcome in the ranks of the Republican Party. Nonetheless, the GOP has its gay supporters who feel drawn to its message of limited government, low taxation, a strong military and a hard line on domestic security.

Although gay Republicans have both an uncomfortable position within the party and are criticized by others outside the Republican Party who accuse them of being “Auntie Toms”, gays within the Republican Party contend that they are fulfilling an important function in that they are educating other Republicans on gay issues, and are exerting a moderating influence on Republican policy debates, which would otherwise be under the unchallenged domination of the extreme religious right wing of the party. They have argued that they represent a truly Republican standpoint concerning the question of state toleration of same-sex relationships, since the Republican ideology of individual liberty and government limitation would logically preclude state involvement in the private lives of its citizens.

Historically, the rank and file of the Republican Party have not been very welcoming to gay members, and the party has been indifferent to anything that even gingerly touches on gay issues. AIDS is a national health crisis that concerns everyone, but because it first appeared among gay men, then-President Ronald Reagan – who was markedly unwilling even to pronounce the words “gay” and “homosexual” in public – was hesitant to commit government resources to combating the disease, and the rate of HIV infection rose to its current pandemic level. Known homosexuals were not appointed to administration jobs in the Reagan years.

George H. W. Bush, the first President Bush and father of the current President, showed more toleration for gay issues. Prior to his election as President, he expressly opposed discrimination against people suffering from AIDS. As President, he actively expressed his opposition to discrimination by helping to guide the Americans with Disabilities Act through Congress and signing it into law. He appointed Ann-Imelda Radice, an openly lesbian conservative Republican, as acting chair of the National Endowment for the Arts.

Generally, George H. W. Bush tried to straddle the party divide between the religiously-dominated right wing and gay Republicans. The chairman of the Bush campaign was willing to meet with representatives from the National Gay & Lesbian Task Force (NGLTF) in February, 1992 to discuss campaign strategy, but he was unprepared for the level of criticism expressed by the NGLTF representatives concerning the inaction of the Bush administration on gay issues, and the low levels of funding provided for research on HIV.

Meanwhile, Bush was facing a challenge for the party’s nomination by Pat Buchanan, who was appealing to the religious right wing of the party by claiming a “culture war” had been declared on traditional American values by homosexuals and feminists. The Reaganite wing of the party was outraged over a tax increase Bush had agreed to. Congressional Republicans, seeing their chances of reelection diminishing as the displeasure of their financially and culturally conservative voter base increased, joined in criticizing Bush, who – to save his reelection chances – made a sharp turn to the right. Bush publicly refuted any support for same-sex marriage, and declared that homosexuality could under no circumstances be considered normal or equal to heterosexuality.

Dan Quayle, Bush’s vice president, made a series of speeches bemoaning the moral decline of the nation. Quayle made a special point of criticizing a fictional television character, Murphy Brown, for having an imaginary child out of wedlock. The Log Cabin Republicans, setting a precedent they will follow in the upcoming election, announced that they could not endorse Bush as a candidate based on his positions on gay issues.

“The days when the gay and lesbian community had to court candidates – when we had to hope that they would pose for pictures with us or circulate a position paper that didn’t say very much – are over. They’re coming to us now.” — Urvashi Vaid, during the 2000 election campaign Bush remained the Republican candidate for president in the 1992 election, but he went down to an overwhelming defeat at the hands of Bill Clinton. Undoubtedly, Bush faced many hurdles to reelection: the Gulf War seemed to end inconclusively, unemployment was high, the economy was in the doldrums and Bush was widely seen to project an attitude of unconcern; still, it is odd how little has been written about the role of the gay vote in unseating Bush, or in electing Clinton. Except for gay fundraisers, no one has commented on the importance of the cash infusion gay donors gave the Clinton campaign, and no one has speculated on what the withholding of gay support meant to the Bush campaign.

Whether a party is willing to acknowledge the contributions of its gay members or not, a history of gay voters in the Republican Party proves both that politically active gay members will organize and assert themselves even in an unwelcoming environment, and that they are in all circumstances a financial force to be reckoned with. The year 1992, the same year in which Pat Buchanan accused homosexuals of conducting a culture war on American values, also saw the first official gay delegates to a Republican National Convention. The Log Cabin Republicans opened their Washington, D.C., lobbying office in 1993 and founded a political action committee in the same year with the intention of raising $100,000 per election cycle to devote to the campaigns of moderate Republicans. The Washington, D.C., office had a permanent staff of six and an annual operating budget of $700,000 by 1996. The Log Cabin Republicans proved their strength in local and state elections. They are credited with making important contributions to the elections of Pete Wilson to the governorship of California, William Weld to the governorship of Massachusetts and Richard Riordan to the office of mayor in Los Angeles. Riordan appointed a gay man as his deputy mayor, and in his 1997 reelection won an estimated 41 percent of the gay vote. Wilson also at first rewarded his gay supporters with appointments before turning to the right in his second term and supporting propositions outlawing same-sex marriage. His political star faded during his second term; although he was the governor of California, he was virtually ignored when the Republicans held their national convention in San Diego in 1996 during Bob Dole’s run for the presidency, and he was unable to make a transition to national politics. William Weld introduced pro-gay legislation recognizing the rights of domestic partners to pensions and healthcare; he was later in his career punished for his pro-gay stance when his nomination as ambassador to Mexico was blocked in the Senate by Jesse Helms, along with other conservatives. Log Cabin Republicans in all contributed $76,000 in 1996 to the campaigns of moderate Republican on the state and local level. Sen. Bob Dole came in for criticism in the same year when his presidential campaign refused a $1,000 contribution because it came from the Log Cabin Republicans. He was forced to apologize and accept the money.

Campaign 2000: Gays take to the stage

Elections in the year 2000 marked another milestone in the development of the gay voting block. It was beginning to dawn on the Republican party elite, after eight years in opposition, that fuming about the moral decline of the nation and the triumph of the homosexual agenda was not attracting voters or winning elections. Meanwhile, the Democrats were enjoying a cozy and highly profitable relationship with the gay voting block. Both parties decided to become more interested in gay issues for the next cycle of elections.

Log Cabin Republicans noted the change in their party and welcomed it. Their newsletter for August 11, 1999 featured an article that began “Prominent Republican candidates for president are creating an atmosphere that is subtly but fundamentally more inviting for gay and lesbian voters than party leaders have been in recent memory.” It noted that the top three contenders – George W. Bush, John McCain and Elizabeth Dole – “have all signaled an openness to gay supporters, including a willingness to appoint them to positions like ambassadorships in their Administrations.” The article admitted that none of the candidates were converts on such issues as same-sex marriage, but all of them were willing to show more toleration on gay issues and the issue of abortion to appeal to a wider range of voters beyond the party’s conservative base. The change “also reflects the continued growing political influence of gay donors and gay voters across party lines.”

Then-executive director of the Log Cabin Republicans, Rich Tafel, is quoted in the article as saying, “The tone has totally changed. What I hear is gay Republicans enthusiastic about the tone being set by the leading candidates. It looks like Republicans for the first time are saying, ‘This is a community I’m not going to alienate and maybe I want to reach out to it.’ That’s kind of a shocking revelation.” The article noted that Democrats had long accepted and enjoyed gay political support, stressing that gay voters “tend to be generous financially and active politically.” It pointed out that the top two Democratic contenders – Al Gore and Bill Bradley – had fundraisers who worked specifically with gay donors.

This newfound tolerance for gay voters expressed itself primarily in a willingness on the part of candidates to employ openly gay people in their administrations. George W. Bush put on record that “If someone can do a job, and a job that he’s qualified for, that person ought to be allowed to do his job.” Elizabeth Dole, the wife of the previous presidential candidate Bob Dole, said in an NBC interview that everyone would be welcome in an administration headed by her. Commenting on her husband’s refusal of the $1,000 donation from the Log Cabin Republicans, she assured the nation that if she received a check from the same organization, “I would not turn it away.” John McCain had already gone so far as to employ a gay man. He had named Jim Kolbe, a representative from Arizona and the only openly gay Republican in the House, to his national steering committee, and promised in the future to hire on merit alone. William Kristol, who had been chief of staff to Dan Quayle when he was vice president, claimed that “The Republican establishment does not want to fight the conservative culture war, partly because they think it’s a losing fight but more importantly, they don’t believe in it.”

The article did admit that some Republican activists remained adamantly opposed to any concessions in the area of gay rights. It specifically mentioned publishing heir Steve Forbes, and politicians Gary Bauer and Alan Keyes, as disapproving of any outreach to gay voters. It drew the distinction, however, that these men were not members of the Republican establishment. It concluded that anti-gay sentiment in the party had become less strident, remarking that most politicians preferred simply to avoid the issue.

Activists on the liberal end of the spectrum also noted a change in the preliminaries to the 2000 elections. Former San Diegan Urvashi Vaid, now director of the Policy Institute of the NGLTF, said: “The days when the gay and lesbian community had to court candidates – when we had to hope that they would pose for pictures with us or circulate a position paper that didn’t say very much – are over. They’re coming to us now. From the perspective of just a few years ago, it’s extraordinary to be able to say that we have major contenders who are going out of their way to reach our community. We’re not begging the presidential candidates and their campaigns for recognition; they’re begging gays and lesbians for votes and for money.”

Al Gore launched into his 2000 presidential campaign in May, 1999 by meeting with 45 prominent lesbian and gay community activists in Washington, D.C., including executive and board members of the NGLTF, AIDS Action, the HRC, the Gay and Lesbian Victory Fund, The National Black, Lesbian and Gay Task Force and the National Latina/Latino Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Organization. He then left for California to attend the June Pride month activities in San Francisco and Los Angeles. It was an amazing effort, but even more amazing was the fact that everywhere he went, he found that his chief rival for the Democratic presidential nomination, Senator Bill Bradley of New Jersey, had been there before him. Both men knew the value of the support they were competing for – most certainly in the monetary sense. Gore’s wife, Tipper, had been the featured speaker at the first-ever fundraising event in Washington, D.C, that was aimed specifically at lesbian and gay voters that July. The event raised $150,000.

Politicians taking a stand – or not

Gay voters would certainly be justified in asking what they were getting in return for their substantial political and financial support, but from the standpoint of the candidate, it was a question that was much better left unasked.

“Whatever George W. Bush had said earlier about hiring practicing homosexuals, after his election, he appointed 15 openly gay people to his administration. As a gesture of gratitude to the Log Cabin Republicans for their support, he invited 50 LCR leaders to an official briefing at the White House. This was the first time that a Republican president had ever invited GLBT activists to the White House.”

While it was true that both Democratic frontrunners Gore and Bradley supported the adoption of a national hate-crime law, and both supported the Employment Non-Discrimination Act, neither of these issues went to the core of interest for gay voters. Both candidates had gone on record as opposing same-sex marriage. Gore was in California when the battle for Proposition 22, which forbade same-sex marriage, was in full swing. Rather then opposing the measure, Gore merely promised to study it. Neither candidate supported gay adoptions, federal domestic partnership protections or a major re-direction of policy in healthcare issues. Both men had voted for DOMA, the 1996 federal Defense of Marriage Act engineered and supported by the Christian right and introduced into Congress by a representative from Georgia who had been married three times, which barred gays and lesbians from marrying members of their own sex, and clearly had the purpose of stirring up homophobic prejudices on a national level.

The situation seemed even murkier among the Republicans. George W. Bush had expressed his opposition not only to same-sex marriage, but to any form of civil partnership or domestic benefits for same-sex couples. He was on record as supporting Texas’ anti-sodomy law. He disapproved of the Employment Non-Discrimination Act, and he is credited with blocking the passage of a hate-crime bill in Texas, which included gays among the protected groups. The bill had already passed the Texas House of Representatives by an 84-63 vote, and enjoyed some Republican support. The Texas Legislature had already passed two earlier hate-crime bills in 1995 and 1997, and the passage of the then-current bill seemed especially pressing in the wake of the racially-motivated killing of James Byrd, a black man who had been dragged to death behind a pick-up truck. According to Diane Hardy-Garcia, executive director of the Lesbian/Gay Rights Lobby of Texas, Bush began pressuring state senators to vote against the bill in private meetings. Members of the Byrd family met with Bush to solicit his support, but he remained firm in his opposition, apparently because of the inclusion of gays and lesbians among the protected groups. Even while the Log Cabin Republicans were publicizing Bush’s willingness to hire qualified gay supporters, Cal Thomas, a conservative columnist, was reporting that Bush promised he would never hire a “practicing homosexual.” When Log Cabin requested a meeting with Bush to clarify the issue, Bush refused. The Log Cabin Republicans then turned their support to the campaign of John McCain, raising $40,000 for his election. It was only after Bush’s nomination as candidate became certain that he was willing to meet with gay activists. Bush called himself a better man for the meeting, and claimed he’d found a new understanding of gay issues.

The 2000 Republican National Convention was a study in contradictions. Speeches praised the party for its ideology of big-tent inclusiveness. Jim Kolbe became the first openly gay elected official to address the party convention. However, many delegates left the hall during his speech or turned their backs on him to express their protest at the event. Republican politicians accepted donations from the Log Cabin Republicans, but the NRCC Issues Book 2000 instructed candidates to say that any legislation promoting gay rights “would allow radical homosexuals to impose their lifestyle choices upon everyone else at our workplace and schools.”

Rival candidates tried to score points off each other by accusing their competitors of being too close to the homosexual agenda, while the LCR spent almost $500,000 for the party to promote voter turnout and publicize George W. Bush’s record in swing states. Their ads targeted women, suburbanites and independents in particular.

Whatever George W. Bush had said earlier about hiring practicing homosexuals, after his election, he appointed 15 openly gay people to his administration. As a gesture of gratitude to the Log Cabin Republicans for their support, he invited 50 LCR leaders to an official briefing at the White House. This was the first time that a Republican president had ever invited GLBT activists to the White House. The Log Cabin Republicans had chapters in all 50 states by 2003, and a permanent staff of 24 full-time employees. The acceptance of gay activists seemed assured in the new administration, but the Christian right wing of the party had not given up their opposition.

Marital problems

The Supreme Court decision in Lawrence v. Texas in March of 2003, which overturned Texas’ sodomy law, seemed to upset the balance between the different wings of the Republican Party. Senator Rick Santorum, R-Pa., claimed the decision would lead to permitting incest, bigamy and bestiality. The party’s right wing renewed their demands for a plank in the party platform which would explicitly oppose same-sex marriage. They furthermore wanted to amend the Constitution to define marriage as a union of a man and a woman.

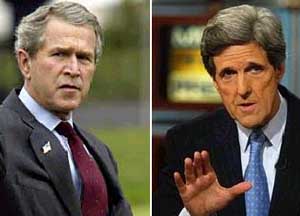

George W. Bush made this demand his own, and in a sharpened form. The Republican leadership now supports an amendment that would not only ban same-sex marriage, but would call into question existing domestic partnership laws such as those that exist in California. It should be pointed out that the Democratic leadership offers only a minimally better choice. John Kerry has not expressed support for a constitutional amendment, but he does want to amend the state constitution of Massachusetts to ban same-sex marriages.

The battle over same-sex marriage has led to history repeating itself. Just as the Log Cabin Republicans withheld their support for George H. W. Bush in 1992, the LCR has refused to endorse George W. Bush for president in 2004.

Patrick Guerriero, the current executive director of the Log Cabin Republicans, blames presidential advisor Karl Rove for the current disunity in the party. He claims that Rove is convinced that Bush’s policy of gay toleration kept 4 million evangelicals from voting in the last election. Bush and Rove apparently believe that by running a campaign that appeals to the far right, they will win a decisive victory in the 2004 election. As we all remember, the last election was extremely close, with Al Gore even winning the majority of the popular vote. Log Cabin Republicans claim that approximately 1 million gay voters voted for Bush in the last election. His victory would have been impossible without their support, especially if we accept the Log Cabin Republican claim that roughly 50,000 gays and lesbians voted for Bush in the key Florida election, the state that decided the outcome of the election and which Bush won by only a few hundred votes.

The gay vote: 2004

The 2004 election will be extremely important to the aspirations of America’s GLBT community, for both the obvious and less obvious reasons. If Bush is reelected, the GLBT community will be faced with life under an administration that seeks support among that community’s opponents. It seems plausible that a second Bush administration will seek to undo all progress that the gay movement has made over the last 40 years in an effort to appeal to its right-wing base.

If, however, Bush is defeated, it should raise some central questions about the importance and decisiveness of the gay vote. We should remember that American governments are elected by a relatively small number of those who are qualified to vote. Only 51 percent of those eligible to vote took part in the last election. The relative size of a voting block is far less important than the voting discipline of that block, and the gay block has proved time and again that it has that discipline. If Bush is defeated, the mainstream press and analysts will see the cause in a poor economy or the war in Iraq.

Looking back over the history of the gay vote, however, we should perhaps pay more attention to the distribution of the numbers. A future analysis of the 2004 election should investigate the possibility that the gay vote under the current conditions of low voter turnout is itself strong enough to make or break a presidential campaign. If that assumption is proven in the next election, then gay voters should no longer be satisfied with the sops that mainstream politicians have so far given them, but should demand that their issues by treated as matters of central concern.

GLBT voters should, in any case, demand to be treated with the seriousness that their contributions warrant.

|

|

Copyright © 2003-2026 Uptown Publications