-

- Judge upholds high school dress code in case of anti-gay T-shirt

- The Center hosts tax seminar for GLBT couples

- Lesbian couple settles discrimination suit against country club

- Man gets piece of ear bitten off in what police are calling a hate crime

- County veterans told ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ doesn’t work

- Logo launches on Time Warner Cable

- obituary

- Community News

-

- Clinton takes responsibility for vote on Iraq war

- Rell says she’ll veto a same-sex marriage bill

- Bills would give state recognition to same-sex unions in Hawaii

- NYC to launch an official city condom with possible subway theme

- Kerry says he will not run for president in 2008

- Anti-bullying measure picking up steam

- National News Briefs

- World News Briefs

feature

Understanding HIV in black America

Published Thursday, 01-Feb-2007 in issue 997

The numbers are staggering

Two percent of the African-American population is HIV positive. That’s one in every 50 African-Americans in the country. Half of them are not getting medical care.

African-American men are five times more likely than Hispanic men and six times more likely than white men to become infected, according to a study by the Center for Disease Control (CDC) on HIV infections among men who have sex with other men (MSM).

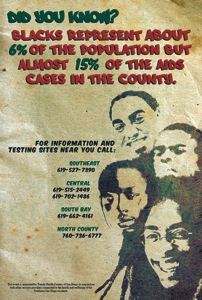

The rate of AIDS cases in African-Americans is more than four times that of whites and nearly three times that of Hispanics, according to the Health and Human Services Agency of San Diego County. Further, while African-Americans make up only 6 percent of the county’s population, they account for 15 percent of new HIV and AIDS cases.

African-Americans account for 12.4 percent of the U.S. population and 54 percent of the 40,000 new HIV infections each year, according to the CDC. While the rate hasn’t always been this high, it has been steadily climbing. In 1994, the CDC estimated that African-Americans accounted for 21 percent of new HIV infections. In 2000, that number rose to 30 percent. Six years later, it’s topped 50 percent.

The Black AIDS Institute calls the disease “genocide.”

For many, the time to act is now. The California Black Caucus will observe Feb. 7 as National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day. Caucus members will wear T-shirts that ask the question, “Got AIDS? How do you know?” in an attempt to encourage African-Americans to get screened for HIV.

The National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day is a national mobilization effort to encourage African-Americans across the nation to get educated, tested and treated for HIV and AIDS.

African-Americans were the only ethnic group to name HIV/AIDS as the No. 1 health problem in the U.S., according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Nearly half believe African - Americans are “losing ground” in the fight against HIV/AIDS domestically. While it may be a collective concern, the proportion of African-Americans saying they are personally concerned about becoming infected has declined since the mid-1990s. At the same time, the actual rate of infection has more than doubled.

Determining the reason for the disproportionate rate of African-Americans with HIV is a complex discussion. There is no easy answer. However, perhaps by deconstructing parts of the equation, we can come to a better understanding of where to begin addressing the crisis at hand.

Identity

Franklin Coffey, 42, of North Park, has been living with HIV for 14 years. Coffey, who is African-American, says part of the issue is the way we frame discussions.

“The second you start using words like gay and bisexual, you are using white people’s words,” Coffey says. He argues that most African-American men who have sex with other men don’t identify with those labels.

The fact is, Coffey says, most African-American MSM don’t get past their primary identity of being African-American. “Look at it this way, If you walked up to a group of people in Hillcrest, and I mean they have to be men who are having sex with other men, and asked them to give you a label for who they are, most white guys would say they are gay. Most Latinos would say they are Latino, or if their family was originally from Mexico, they might even say they are Mexican. Most blacks would say they are black or African-American. We tend to identify ourselves by the primary point that removes us from the mainstream culture.”

Lorenzo Herman is the patient education programs coordinator at UCSD’s Owens Clinic. His job is to provide health education and counseling to HIV patients. Herman agrees with Coffey.

“The majority of African-American men who come into the clinic do not identify as gay or bisexual,” Herman says. “They just aren’t terms that are commonly used by the men who come in. Their primary identity is being black. And even if they could get past the primary identity to a secondary one – say, being gay – then you have to go another level to get to the HIV status. And since the majority of services for men who have sex with men who are HIV positive are put in the language of gay and bisexual, a lot of black men are turned off by it. They rarely describe themselves as gay or bisexual.”

Popular culture plays a pivotal role in language and culture

“Look at who we see as gay on TV,” Herman says. “Being gay is defined in the media by ‘Will & Grace’ and [The Adventures of Priscilla Queen of the Desert]. Black men are not supported in a white gay community for the same reasons that racism exists in the general population. It’s about identifying or not.”

Kenyon Farrow is a writer and activist in Brooklyn, N.Y. Farrow is known for his keen insight into issues of both race and sexuality. In a widely praised essay, “Is Gay Marriage Anti-Black?” Farrow makes the following observations about race and sexuality in the African-American community.

For young gay and bisexual men of all ethnicities 77 percent of those who test positive for HIV did not know that they were HIV-positive. Of these, a startling 91 percent are African-American. “Despite our internal diversity, we are at a time (for the last 30 years) when black people are portrayed in the mass media – mostly through hip-hop culture – as being hyper-sexual and hyper-heterosexual to be specific,” Farrow writes. “Nowhere is the performance of black masculinity more prevalent than in hip-hop culture, which is where the most palpable form of homophobia in American culture currently resides.”

Farrow points to the visual impact of music videos as being as important as the song content. In particular, Farrow has spoken out against “gangsta” and black nationalist revolutionary forms of masculinity, including the recent DMX video and song “Where the Hood At?”

“The song suggests that the ‘faggot’ can and will never be part of the ‘hood’ for he is not a man,” Farrow writes. “The song and video are particularly targeted at black men who are not out of the closet and considered on the ‘down low.’ Although challenged by DMX, the image of the ‘down low’ brother is another form of performance of black masculinity, regardless of actual sexual preference.”

And anytime you have a group of people who struggle with their identity, Herman says, there are bound to be resultant effects.

“Part of it is the racism within the mainstream gay community that keeps black men from getting services,” Herman explains. “And then there is the homophobia within the black community – such a strong stigma about being gay – to even acknowledge that being gay comes from the inside. And so we end up with men who are struggling with substance abuse, alcohol and drugs. We have a very unhealthy mental health situation because many of the young guys we see have mental health issues that are not being addressed, such as the substance abuse. It’s not just about medical, but the mental and social assistance as well.”

The ‘down low’ myth

When J. L. King appeared on “The Oprah Winfrey Show” on April 16, 2004, to promote his book, On the Down Low: A Journey into the Lives of ‘Straight’ Black Men Who Sleep with Men, many of the issues that face the African-American community faces around HIV and AIDS were brought to the surface.

,Charles Ramsey, of Normal Heights, argues, King’s book – which put the phrase “down low” into the mainstream – had some unintended effects.

“The primary thing that happened was the blame game,” Ramsey said. “Suddenly, everyone started blaming black men who slept around on their wives – essentially bisexual black men – for the HIV infections in our [African-American] community. And that took the focus away from prevention efforts in the black gay community, which was already uncomfortable enough for us, and put it back on something everyone can agree is bad: cheating husbands. The truth is that if you look at how people get infected, the population we call ‘down low bruthas’ is pretty small.”

The July 2005 Journal of the National Medical Association included a review of research conducted by a team of HIV/AIDS specialists from the CDC titled “Focusing ‘Down-Low’: Bisexual Black Men, HIV Risk and Heterosexual Transmission.” It responds to the assumption that the primary transmission of HIV – and therefore the target for education and prevention – is men having sex with men on the “down low.”

According to the study: “When you look at the whole issue of what down low means, it really translates into the issue of disclosure – who you’re telling and who you’re not telling – and may be dependent upon the nature of the relationship and gender of the individual with whom you’re having sex. If some black MSM are secretively bisexual, studies have demonstrated that they’re more likely to have more female partners than disclosing black MSM, and thus are more likely to have unprotected sex with these female partners. However, these same men report lower rates of unprotected sex with their male sexual partners than disclosing MSM…. If bisexual black men represent a small proportion of black men in the United States, and non-disclosing black men are less likely to be HIV positive than gay-identified men or engage in high-risk behavior, then is this population primarily responsible for the HIV epidemic among heterosexual black women?”

Studies have consistently shown that 40 percent of AIDS cases among African-American women are a result of intravenous drug use. While another 40 percent are attributed to sexual behavior that is deemed risky, such as intercourse without a condom, what is not known is what percentage of those having risky sex are infected by heterosexual, bisexual or homosexual men.

“The flawed logic often perpetuated by the media is that only homosexual men have HIV, bisexual men only contract HIV through homosexual behavior, and the only way black women contract HIV is through sexual contact with these bisexual men. Homosexuals are not the only ones with HIV, and just because someone keeps their same-sex behavior secretive doesn’t necessarily mean that they are irresponsible with condom use…. Subscribing to the down-low theory takes the focus away from the behavior that transmits HIV. As a society, we have to think deeper and more critically about what the reasons are for the high rates of HIV in our community.”

Phyllis Jackson is the HIV/AIDS program services coordinator for NMA Comprehensive Health Center in San Diego.

“Being on the ‘down low’ is not unique to the African-American community,” Jackson says. “Whether you call it ‘down low’ or ‘stealth,’ it’s about disclosure, not race. The term ‘down low’ has unfairly become a label, a stigma associated with HIV - positive gay black males.”

And Ramsey, that seems like an easy out for a community desperately in search of help.

“Isn’t it easier to look at this situation – where the numbers of whites getting infected is dropping while the number of blacks is growing – and find a convenient scapegoat? It’s what the black man is best at, right? Being the scapegoat for our society’s problems.”

The church

Rev. Madison Shockley, minister at Pilgrim United Church of Christ in San Diego, believes the church is the biggest obstacle in the lives of GLBT African-Americans.

Refering to the phrase “God made Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve,” Shockley said, “I don’t know, but I bet it was a black preacher who first uttered that phrase. It’s sad for a church that’s historically stood for civil rights, and certainly civil rights for itself and civil rights for all persons – so it was doubly tragic.”

Jackie Thompson, 28, a self-described “proud black dyke,” believes the church would rather talk about anything except homosexuality.

“It used to be that there was a dangerous silence in our churches around sexuality, and no one – and I mean no one – talked about HIV and AIDS in the context of African-Americans,” Thompson says. “And then reports came out that HIV was the No. 1 killer among African-American women. How could the church ignore that?”

In fact, HIV is the leading cause of death among African-American women ages 25-34.

“Here you have a church that is famous for social justice, and we are ignoring the greatest threat to our communities yet,” Thompson says. “At what point do you stop harping on gangs, poverty, crime and homelessness – all important issues, for sure – as your social justice issues and start looking at what is really killing our sisters, mothers, daughters, wives? And church leaders are historically and currently our black leaders. Reverend [Martin Luther] King [Jr.], Reverend [Jesse] Jackson, Reverend [Al] Sharpton. ”

Coffey agrees.

“The black church gave rise to the civil rights movement,” Coffey says. “It helped begin the process of righting a century of oppression. So why stay silent on the most important issue facing the African-American community in the 21st century?”

Although African-American teens account for 15 percent of U.S. teenagers (ages 13-19), they accounted for 73 percent of new AIDS cases reported among teens in 2004.

“Anyone with a head on their shoulders can see that unless we start talking about this, getting it out into the open as a discussion, it isn’t going to go away,” Coffey says. “In fact, if we don’t do something, it’s going to decimate our community. You know how they teach you that when a ship goes down, we’re supposed to save the women and children first? Well, apparently we didn’t learn that lesson very well.”

One of the primary factors in the church’s silence, said Coffey, is that somehow HIV and AIDS is a strictly gay disease. And clearly the statistics in the African-American community don’t support that, Coffey says.

“Look, if the church doesn’t want to talk about homosexuality, fine,” Coffey says. “But for God’s sake – and I mean that in the strictest religious sense – for God’s sake, we have to at least talk about sexuality. Teens are having sex. You have two choices: Bury your head in the sand and bury your children, or talk about it.”

The media

Seventy-one percent of us get our information on HIV and AIDS from the media, according to the Henry J. Kaiser Foundation. Only 9 percent get information from our doctors, and 6 percent from our families. In other words, the media is the single largest source of information about HIV and AIDS.

And yet, most would agree that the media has greatly ignored, either intentionally or not, the African-American community.

Jeremy Simmons, 53, of University Heights, has a theory about why HIV has been portrayed as a gay white man’s disease for so long.

“I think the media has been afraid that they will be seen as blaming the African-American community for a disease that is commonly thought to have arrived in the U.S. from Africa,” Simmons says. “I think that the media looked at this way back in the 1980s and said, ‘We are going to make a conscious effort to avoid that sort of racist connection.’ Ironic, isn’t it? Maybe someone was trying to do some good, and you know what they say, ‘No good deed goes unpunished.’

If I was African and HIV positive, they would pay attention, but the minute I stop being African and start being American, the media and funding stops.”

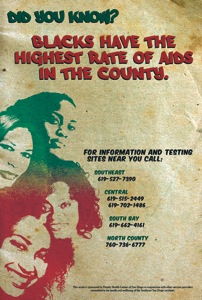

In San Diego, however, there is a ray of hope on the horizon. According to Bob Lewis, director of HIV services at Family Health Centers of San Diego (FHCSD), FHCSD is launching a new campaign specifically targeting the African-American community. The campaign will appear on several billboards and bus shelters in southeast San Diego, as well as in full page ads in the San Diego Voice & Viewpoint.

“We developed the multiple print ads under the guidance of an advisory group comprised of African-American community members, service providers and community leaders,” Bob said. “The group included representation from both the straight and gay/lesbian communities. During the development process, the group decided that in order to maximize the effectiveness of the message, the campaign should not target any specific risk group. Along these lines, the group decided that images reflecting the great diversity within the African-American community were important. During the meetings, it was stated that there is a significant amount of denial and misinformation in the community; therefore, the group also decided we should use actual statistics to illustrate the severity of the problem.”

“The flawed logic often perpetuated by the media is that only homosexual men have HIV, bisexual men only contract HIV through homosexual behavior, and the only way black women contract HIV is through sexual contact with these bisexual men.”

Some members of the community have even grander dreams.

Ramsey puts it this way: “Can you imagine the power of Oprah doing a show where she went to get tested for HIV and told the millions of people who watch her show, a large chunk of which are African-American, to go get tested? Or what about if [Chicago Bears player] Charles Tillman did a Super Bowl service announcement commercial where he was getting tested for HIV, looked at the camera, and said, ‘The true test of a champion happens every six months?’”

Health care access

When thinking about the issues of health care and the African-American community, part of the issue is that we need a medical system that reflects the communities it serves, Jackson says.

“You have got to have African-Americans and other people in the system helping people,” Jackson says. “Otherwise you will have these assumptions that the medical professionals don’t care about everyone in the community. We need programs that are relevant culturally to the African-American communities. We need programs that speak the community’s language, that show the members of our health care community are interested and that make people feel comfortable. Sometimes it comes down to what you have on the walls of the facility. How do we acknowledge minority communities in the facility?”

Martin Lewis is an emergency room nurse. He sees the issues of race and health care every day.

“I’m the only black male R.N. at the hospital,” Martin explains. “The only other black men at our facility are the security guard and the guy who takes your ticket at the parking garage.”

And the result of a lack of representation in health care? A significant portion of the HIV-positive African-American population remains out of care altogether. According to San Diego County health data, more than 50 percent of African-Americans with HIV/AIDS are out of care.

“Look at my dad,” Martin says. “He was a corrections officer for 30 years, with a great medical plan and pension. But he wouldn’t go the doctor. African-Americans typically don’t seek medical treatment for wellness and prevention. We don’t believe in that. Unless you’ve been stabbed or had a stroke, there’s no need to see a doctor.”

Martin’s dad had a stroke when he was 64.

“I’ve been a nurse since 1992 and was a Navy corpsman before that. But do you think I could get him to go the doctor for a check up? And then his cholesterol was 700. And this was a man who had access to insurance and health care.”

Bob isn’t surprised.

“Many communities, including the African-American/black community, are apprehensive when dealing with agencies and organizations where they do not see staff that represents their community,” Bob explains. “This limits access for communities to needed health and social services.”

Mistrust of the medical community is not completely unfounded for the African-American community. Even our nation’s recent history is riddled with violations of trust. The most memorable, of course, is the Tuskagee Syphilis Study, where departments of pubic health continually denied treatment to African-American men, some of whom were deliberately exposed to syphilis, from 1928 to as recently as 1972.

The American Red Cross complied with demands for racial labeling of blood and blood products during World War II and continued the practice for decades before finally discontinuing it.

And it’s not just a mistrust of white medical professionals, Martin explains.

“We had a noncompliant 50-year-old African-American diabetic in the ER recently,” Martin says. “I went through everything and then gave him his discharge instructions. As soon as I turned around and pulled the curtain so that he could get dressed, I heard him confirming every instruction I gave with the white female technician. It was unbelievable.”

Jill Kunkel is a nurse and the director of operations at UCSD’s Antiviral Research Center (AVRC) in Hillcrest. She is responsible for the hiring of employees at the clinic.

“Having someone at the front desk who is African-American, having someone who is doing the testing, a nurse who is African-American, is really important,” Kunkel explains. “Just as it is important, for example, to have a nurse who speaks Spanish and is Latino/Latina.”

In particular, getting members of the African-American community to access health care is a challenge, Kunkel says.

“HIV in San Diego is essentially driven by white men,” Kunkel says. “There are few people of color at the front of the discussion. Add to that the stigma that HIV carries in the African-American community, which is significantly greater than in the white community, and you have a community that is the most difficult to reach. There are the normal social barriers and then that historical mistrust of health care.”

AVRC has one of the largest early intervention programs in the city.

“It’s a program designed for people who are uninsured or disenfranchised,” Kunkel explains. “Maybe they just found out [they are HIV positive], or maybe they have known and not done anything about it. There are four components to it, all of which are critical. First, there is the medical component, where you get your routine blood work, general medical care related to HIV. Second, there is the psychological component, where patients can meet for hour-long sessions and talk about those issues they have in mental health. Third, we have the health education component, where we have a health educator talking to the patient about what HIV is and what it means, what the medications mean, etc. Fourth, we have the prevention piece, where we talk to people about how to deal with their family and relationships now that they are positive. The great thing about our program is that the last three components are all available to families and significant others of the patient. We need to do a better job of reaching those who are uninsured, the working poor, disenfranchised or have just fallen through the cracks. Maybe they have different priorities and health care hasn’t been one of them.”

Beyond ensuring that African-Americans are reflected in the health care area, there is another barrier to break down, Jackson says, a barrier that AVRC addresses right from the start.

“We need to stop thinking of mental health care and physical health care as binary,” Jackson says. “I think when we talk about services available, it’s important to include both equally.”

One of the most significant effects of a community that is not trusting of the health care system is that they go longer without knowing their status. Studies from the CDC indicate that 56 percent of all “late testers,” those who develop AIDS within a year of getting tested, are African-American.

Martin isn’t the least bit surprised at these numbers.

“People come in a lot and have these mysterious illnesses, signs, symptoms, and you know that there is a high probability that they are HIV positive,” Martin explains. “But they simply won’t consent to be tested. The African-American community, on the whole, is afraid of testing. Or, more specifically, afraid of being told they are positive. And what’s really tragic is when people bring their kids in, teenagers or whatnot, and won’t consent to have them tested. And all of these people are going out and continuing to have sex, most often in the same risky way in which they became infected in the first place.”

Knowledge of one’s HIV status appears to be particularly low in some populations. For young (15-29) gay and bisexual men of all ethnicities, 77 percent of those who test positive for HIV did not know that they were HIV-positive. Of these, a startling 91 percent are African-American.

“I don’t think it’s going to surprise anyone that someone might test positive and not have known they were,” Ramsey says. “But those numbers are pretty shocking. At what point do we get the message?”

The AVRC is also opening a new screening program on Feb. 2 in conjunction with The Center.

“Two days a week, we are going to be at The Center’s Health Center on El Cajon Boulevard offering rapid testing,” Kunkel explains. “Basically rapid testing is where the person comes in, gets a saliva test – no blood draws – they wait one hour instead of one week with a number to come back and all of that, and we tell them on the spot. We will be offering counseling and all of the regular services.”

There are many reasons why rapid testing is critical, Kunkel says. First, there is the need for people to come in for one appointment and get the results back rather than wait a week. Second, people need to know as soon as possible if they test positive. A person’s viral load in the first three months of infection is at its highest, and therefore carries the highest risk of transmission.

“Those who are acutely infected or just recently infected,” Kunkel explains, “they are very infectious during this three month period, give or take a few months. The idea is that we get them in, get them tested and get them into health care.”

While the program will initially be at The Center’s Health Center on El Cajon Boulevard, Kunkel says the hope is to start up these clinics all over San Diego.

Looking forward

In conjunction with National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day, there will be events held in southeast San Diego sponsored by FHCSD and in Oceanside sponsored by the Vista Community Clinic.

But the real work of education and prevention will continue through more systemic change, Bob says.

“Nowhere is the performance of black masculinity more prevalent than in hip-hop culture, which is where the most palpable form of homophobia in American-culture currently resides.”

“To accomplish this goal, we must also increase awareness of the impact on the community and encourage individuals at risk to get tested, both of which will hopefully have an indirect prevention effect” he says. “The future needs to include service agencies that are not only culturally sensitive to the black/African-American, but employ and have black/African-American individuals part of the decision-making process at not only the program level but at the administrative level. Moreover, these agencies need to be willing and able to address the ongoing issues of racism and homophobia that are still very present in our community and also serve as very effective barriers to information and care.”

Martin agrees. He points to a key systemic change that needs to happen: sex education.

“We need to rethink the way we teach kids about sex,” Martin explains. “The way we teach kids about sex, we put it in terms of a man and a woman. For most kids like me, then, I just shut down and stopped listening because I didn’t think any of that applied to me. So when it came to the discussion of condoms, my teachers always put it in context of men and women, and so how would I know to apply that to the way I was having sex?”

For Jackson, it comes down to the age-old idea of just doing what is common sense.

“African-Americans are not the exception to the rule when it comes to HIV,” Jackson says. “We need to focus on empathy and plain common sense. Just treat me like I’m human.”

For information on events scheduled in conjunction with National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day, call Family Health Centers of San Diego at (619) 515-2424 and the Vista Community Clinic at (760) 631-5000.

|

|

Copyright © 2003-2025 Uptown Publications